The waiter placed the duo of chicken dishes on the table at 1880, a private members’ club in Singapore. On one dark ceramic plate was a golden maple waffle shoring up a crisp piece of chicken, while the other dish was hidden within a bamboo steamer. Entrepreneur Stephanie Dickson, who has been a vegetarian for most of her life, lifted the lid to find a plump bao bun filled with crispy chicken drizzled with sesame and orange sauce. “The chicken pieces looked really crispy and tender and the meat was really moist,” she describes. On the surface, this looked like any restaurant setting, but what was different about the menu was the key ingredient came from a laboratory.

Lab meat can also be called cell-based meat or cultured meat, although the companies behind the products prefer the more palatable-sounding “cultured meat.” Dickson was one of the first people in the world to eat this commercially-sold cultured meat. On December 19, 2020, the San Francisco-based company Eat Just was given a license by the Singapore Food Agency to sell its meat in restaurants. Singapore is the first country in the world to allow cultured meat to be sold to the public.

“I was curious to see how I would feel about it,” says Dickson. “But I didn’t experience what they call the ‘yuck’ factor. In fact, I thought the fact the chicken wasn’t slaughtered to create the dishes was quite incredible.”

Alternative food companies, such as Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat, are a familiar sight in Singapore, but GOOD Meat from Eat Just is a little different. While the aforementioned plant-based products imitate meat, Eat Just’s cultured chicken is meat. Eat Just is one of a growing number of lab-food companies that are producing chicken, beef and shellfish without the need for the death of an animal.

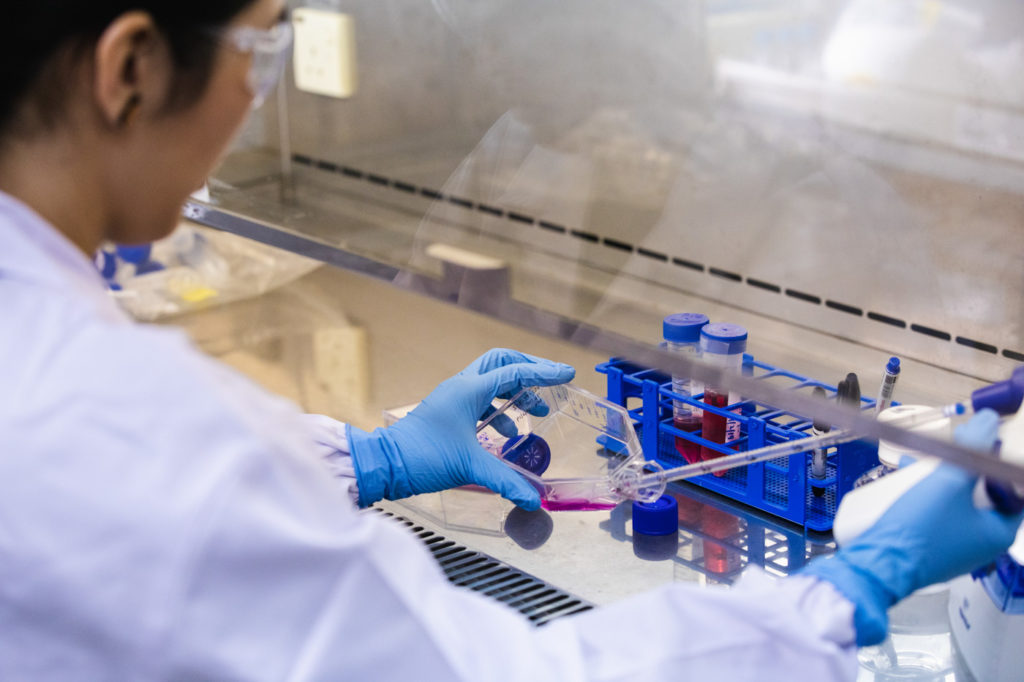

Lab-food companies, using techniques discovered through medical science, are able to take stem cells from live tissue, add them to a nutrient-filled broth, and then place them into a bioreactor (essentially a mechanical greenhouse) where the cells multiply and form connective tissue. In 2013, Mark Post, Professor of Vascular Physiology at Maastricht University, was the first person to create a cell-based meat dish. However, as the initial cost of producing his burger was $325,000 (USD), it understandably prevented it from being rolled out to the masses. But eight years later, Eat Just sold its chicken dishes to diners in Singapore for a more wallet-friendly $17 (USD).

Kearney Management Consulting Firm in Chicago projects 35% of all meat consumed globally by 2040 will be cultured. Josh Tetrick, CEO of Eat Just, Inc., says they want to create a product everyone can afford.

“We are taking everything that is good about meat (the flavors, the connection to it, the nutritionals) and we are eliminating the bad (the slaughter of animals, the deforestation, and the nitrogen run-off into our oceans,” Tetrick explains.

Food scientist Dr. Bryan Quoc Le, who is a consultant for Singapore’s TurtleTree Labs, says lab-grown meat has substantial potential to reduce the environmental impact of meat production. “Animals require enormous amounts of land, water and feed, whereas cultured meat can be grown in a bioreactor that’s carefully controlled,” he says.

“While cultured meat is expensive to produce … I predict that in fifteen years, you’ll start to see it produced at the level where it would be in mainstream supermarkets [worldwide],” Le says. He predicts this would take five years to bring down the cost, five years to pass regulations, and five years for public adoption.

Tetrick believes cultured meat is what the future will look like. “In ten to fifteen years, General Motors won’t be making combustion engine cars, because that’s the way the world is going,” he explains. “[Cultured meat] is not meant to be an option; it’s meant to be the only type of meat we’ll consume.”

While this might seem extreme to some, the potential for cultured meat has been recognised by 1880’s Executive Chef Colin Buchan. The Scottish chef was given the challenge of introducing Eat Just’s chicken to the diners of Singapore.

When Buchan first tasted the poultry, the chef admits he was surprised by its flavor. “The texture and taste of the cultured chicken is just like traditional chicken,” he describes. “The meat tastes more like chicken breast than leg meat,” he explains. “It was easy to handle and slightly bouncy to the touch.”

The Eat Just team is planning to launch a chicken breast in 2021, but at the moment, the meat is only produced in bite-sized chunks, which influences how the dishes are presented to diners. But the chef wasn’t deterred; he was up for the challenge. In order to show what the future of food could look like, Buchan and the Eat Just team decided to use the largest poultry consuming nations—the United States and China—for inspiration while creating recipes. Buchan created the maple waffle chicken dish as a nod to the U.S. and a crispy chicken bao as a nod to China.

While Buchan has worked in Michelin-starred restaurants, including Marco Pierre White’s L’Escargot, Andrew Fairlie’s One Devonshire Gardens, and London’s The Square, he knew on this occasion, the star of the show was the twenty-first-century ingredient. “We didn’t want to overpower the chicken itself, so we used delicate flavors such as sesame and light barbecue to complement the meat,” he describes. “For the chicken-and-waffle dish, the chicken takes the main stage and speaks for itself.”

The chef believes when the production of the cultured chicken increases, it will open up a host of possibilities for chefs around the world. He has noticed diners’ tastes are evolving, and there is an increasing openness to innovative foods such as plant-based options and cultured meat. Plant-based options are seen in Singapore’s restaurants and supermarket freezers, so when Buchan first served the Eat Just chicken dishes to diners at 1880, he added three vegan dishes to the dégustation menu to demonstrate how vegan food is a step in a more sustainable direction.

Buchan says it was an honor to be one of the first chefs in the world to create dishes with and cook cultured chicken. “It’s a historic breakthrough in food technology and a challenge I’ve been excited to explore,” he says. “I’m looking forward to seeing what’s next in terms of new iterations and different meats.”

Whether the future of food will be farm-to-fork or lab-to-plate, Buchan believes it’s not just up to the scientists to come up with solutions, but for the public to think about eating more sustainably. “There are seven billion people on this planet, and there are twenty-three billion chickens reared at any one time. I think we can afford to dial back on our demand for chicken or meat,” he says. The USDA’s Economic Research Service projected that per capita, 44.1 kilograms (97.2 pounds) of chicken will be consumed in 2021. With this level of consumption, it’s clear we need to look at a variety of solutions to serve our protein addiction.

The knowledge that Singapore can grow cell-based meat on its own shores is invaluable to the island-state. While other countries such as Spain and the U.S. are also creating cultured meats, thus far, Singapore is the only country that has allowed the meat to be served to the public.

Once a nation of farmers, its economy is now based on banking, tourism and cargo. The country has gone from growing its own food to importing 90% of what it eats as skyscrapers stand where smallholdings were once farmed. The country’s reliance on other nations for food has made it concentrate on finding alternatives for sustenance. And its desire to be more self-sufficient was brought into sharper focus when the COVID-19 pandemic brought fears of food shortages as borders closed between countries. Singapore recently announced it aims to produce 30% of its own nutritional needs by 2030. It plans to partially accomplish this by increasing food security through futuristic food solutions.

Gaia Foods, which is based in Singapore and run by Vinayaka Srinivas and Thanh Hung Nguyen, two former Duke-NUS Medical University researchers, is growing animal cells on scaffolds so its meat mimics the texture of beef and pork. And Shiok Meats, which is helmed by two Singaporean female stem cell scientists, Dr. Sandhya Sriram and Dr. Kai Yi Ling, is creating lab-grown shrimp and lobster meat. As Asia’s diet is largely centered around fish, Shiok Meats scientists believe this could make a substantial difference in terms of environmental sustainability if you grow shellfish rather than take it from the ocean. The world’s fish consumption is expected to reach 20.9 kilograms (46.1 pounds) per capita by 2023, and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations states that 33% of our planet’s water is already overfished.

At the moment, Shiok Meats’ shellfish costs a whopping $5,000 (USD) per kilogram, but the company aims to reduce the cost to $50 per kilogram when it launches on the market in 2022. The cost can be reduced by growing the cells in nutritious plant-based broth, rather than the pharmaceutical grade nutrient solutions, which they are currently using in their research and development stage. Shiok Meats’ shrimp is currently in minced form, which can be used in popular dishes such as siu mai (steamed dumplings), but their scientists are also working on a crustacean that will take on the familiar shape of shrimp.

When YouGov surveyed Singaporeans about cell-based food in 2017, it was revealed that 51% of Singaporeans would not eat these meats. But Sriram, CEO of Shiok Meats, wants to allay their concerns: “If you think about most foods we eat now, from beverages to biscuits, they were made in a lab.”

With Singapore being a melting pot of different cultures, other lab-food companies have chosen the island-state as its base, including TurtleTree Labs, which is creating the world’s first cell-based milk. It was just awarded a $1 million (SGD) grant from the nonprofit Temasek Foundation to help grow its business and expand throughout Asia. The company takes live stem cells from milk, turns them into mammary cells, and then uses those cells to produce TurtleTree’s full-fat milk. “Our technology is mimicking the environment that is present within living animals,” says Bahren. “Unlike cell-based meat where the cells are consumed, these cells can be reused in the process.” In the future, Bahren adds they have the technology to make low-fat options as well.

Chemist Harith Bahren, who works as a business analyst for TurtleTree Labs, says the animal-free milk will not only solve land-use problems, but it will also be a cleaner product. “TurtleTree milk will not only address the carbon footprint of traditional farming, but the issue of contaminants like PFAS [per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances],” says Bahren. As they create the milk in lab conditions, they choose what can be added—or not added—to the milk.

However, the idea that the cell-based meat can be made healthier interests New York-based registered dietitian Elizabeth Gunner. “Cell-based meat can be manipulated in ways that could be beneficial for the human body. For example, including omega-3 fatty acids could be used instead of saturated fat,” she says. “More time might be required for producers to create a lab-grown meat that is identical in composition and metabolism to farm-raised meat.” Although, it might not be too long before it is sold commercially. Aleph Farms in Israel just unveiled the world’s first cell-based ribeye steak, which incorporates fat and muscle, and Eat Just plans to create a highly-marbled Wagyu beef within two to four years.

Robert Baigrie, Senior Director for Conservation International, who is one of the few diners to taste Eat Just meat in Singapore—and the world—says these developments are the key to the future. He explains, “In a world increasingly impacted by the negative consequences of our existing industrial food systems, [cultured meat’s] potential is very hard to overstate.”

Now, the aim for the cell-based food companies is to increase public awareness of their products and share more information about the meat and how it is made—and to dispel any apprehension by the public. Shiok Meats is already visiting schools and sharing educational videos on its social media in order to be as transparent as possible.

Tetrick says once they can get it onto everyone’s plates and people can see how good the meat is, public opinions will change: “Think about the first time you bought something online, the first time you bought an electric car, or the first time you saw a rover land on Mars,” he says. “Everything is odd and strange, until it’s not.”

Researchers have challenged how beneficial for the environment cultured meat will be. Marco Springmann, an environmental researcher from the University of Oxford, told CNN that lab meat doesn’t solve anything because its energy emissions are so high. However, Tetrick says they have a commitment to protecting the environment. Cultured meat was also found by researchers in Helsinki and Amsterdam to produce up to 96% fewer greenhouse emissions than traditional farming. As they move toward mass-manufacturing, Tetrick says, “It is up to us to watch and monitor that and make sure we are not making something that’s ultimately worse for the environment than the current way of doing it.”

As the global population is expected to increase to nine billion by 2050, Professor Benjamin Horton, Director of the Earth Observatory of Singapore, who studies climate change, says the world’s land and resources will need 70% more food to feed future generations. He believes if we are patient, cell-based meat might provide the solution.

“Cultured meat will evolve continuously in line with new discoveries and advances that optimize the production and quality,” he says. “I believe this progress will be enough for cultured meat to be competitive in comparison to conventional meat and the increasing number of meat substitutes.” Now that sounds like it could be a recipe for success.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.