Although McDonald’s wouldn’t arrive in Moscow until 1990, the seeds of fast food were planted over 50 years earlier during Joseph Stalin’s second Five-Year Plan. That’s when then People’s Commissar of the Food Industry, Anastas Mikoyan, was tasked by Stalin to visit the United States on an intel-gathering, food production research mission in 1936. What Mikoyan discovered, and ate, while on his trip would eventually lead to the translation of several American foods into what is now considered traditional Russian cuisine — this at a time when capitalism and communism stood in almost irreconcilable contrast.

To back up a bit, consider the early 1930s. It was a time of bread lines and unemployment signs. Much of the West lay paralyzed by the Great Depression, and economic collapse threatened what capitalism had promised to rebuild in the decade following World War I. Stalin, however, saw an advantage. With aggressive plans for Soviet industrialization, he sensed the dawn of communism’s shining moment — the chance to elevate what had been a “backward” country to the top rank of global power.

By 1934, after the first of what would be several five-year plans (also officially referenced as Stalin’s Five-Year Plan, a series of goals rolled out every five years), Russia had reported overall industry growth of 213%. This was a massive expansion in transportation, construction, manufacturing and mining at a time when the rest of Europe and the U.S. were struggling through a staggered economic recovery. Soviet cities were humming, fueled by a steady influx of laborers and with enough grain supplied to these urban centers that, as Stalin eyed it, surpluses could be sold abroad.

Finally, a modern Russia would be able to compete on the world’s stage against its capitalist rivals. But, what was really going on?

The Five-Year Plan(s)

Stalin rose to power under Vladimir Lenin, founder of the Bolshevik Party, which would later become the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Although not as charismatic as some of his contemporaries, Stalin used cunning maneuvers to win himself party leadership in the years following Lenin’s death in 1924. He was convinced that Russia needed stricter, top-down measures in order to surpass the West, and that Lenin’s more liberal policies of allowing free markets within government control were moving too slow to realize the country’s greatness.

On October 1, 1928, Stalin’s first Five-Year Plan began, an ambitious incentive meant to superspeed modernization with goals of doubling — sometimes tripling — previous outputs from its different industries. Motivated by Bolshevik rhetoric, workers believed they were ushering in communism’s promise of a better, more egalitarian society. Present suffering was discounted in order to achieve future reward, and mythic figures were often created out of celebrated laborers like Alexey Stakhanov, a jackhammer operator who mined 102 tons of coal in under six hours.

In his book “Out of Ashes: A New History of Europe in the Twentieth Century,” Konrad H. Jarausch writes, “Compelled by iron discipline, Russian workers put in twelve-hour days, six days a week, laboring under incredibly harsh conditions beyond their physical capacity … When self-exploitation did not suffice, the state turned to prison and forced-labor-camp convicts, using them especially for the construction of railroads and canals.”

To feed this growing population of ceaseless workers, Stalin needed grain. Prior to the start of the Five-Year Plan, in 1927, there was a provision shortage as wealthier peasants (kulaks) hoarded grain during the winter rather than choosing to sell it on the open market. This outraged Stalin, and his resulting policy of forced collectivization sought to abolish any private farm, including small garden plots for personal use. Landowners thus became laborers who had to rent their land back from the state, either on state-run farms called sovkhoz or through collective farms known as kolkhoz. Production of grain for the state was the top priority.

Collectivization was also intended to industrialize agriculture and kolkhoz were equipped with new machinery, such as tractors, for the first time to increase production. Before reserving any product for themselves, even at the risk of starvation, farmers were expected to meet increasingly high grain quotas, which resulted in growing resistance to joining the kolkhoz. Stalin, through the state police OGPU, turned to class warfare, ruthlessly arresting or murdering kulaks while intimidating peasants and persuading those without land that collectivization was their only hope. In 1928, roughly 1% of Russian peasants worked on collective farms. By 1936, that number had increased to over 90%.

Soviet Ukraine, with its fertile black chernozem soil, was particularly decimated by Stalin collectivization. Unlike in Soviet Russia, where communal farming had traditional roots, Ukrainians resented the loss of private land. They saw it instead as a “second serfdom” to the communist party and a threat to their cultural autonomy. With the power to determine who was a kulak and who wasn’t, the OGPU conducted sweeping deportations of Ukrainian peasants (113,637 people at the start of 1930) to its system of forced labor camps, eventually known as the Gulag. Combined with harsh grain quotas and this dekulakization, collectivization led to man-made famine spreading throughout Ukraine between 1932 to 1933. It’s estimated between 2.4 to 7.5 million Ukrainians died during this time, a period known as the Terror-Famine, or Holodomor. As Timothy Snyder notes in his book, “Bloodlands,” “Hunger was far worse in the cities of Soviet Ukraine than in any city in the Western world. In 1933 … the vast majority of the dead and dying in Soviet Ukraine were peasants, the very people whose labors had brought what bread there was to the cities.”

Refusing to admit anything but progress, Stalin claimed his first Five-Year Plan a success (although none of his stated goals were accurately realized) and plowed ahead with a second plan that officially began in January of 1933. While he scaled back on agriculture, there was renewed emphasis on industrialization, specifically to improve Russia’s roads, railways and canals.

And Stalin still needed an answer for mass-produced, state-sponsored food.

Making Food, Fast

By 1936, Russia’s urban workforce had increased by the tens of millions as laborers left the countryside for work (and food) in its cities. Feeding them was the responsibility of the state, which served three-course style meals in an assembly-line, centralized fashion in public cafeterias. Mikoyan wanted to improve this process, which was his goal in spending two months touring the United States, exploring everything from Macy’s department store, ballpark stadiums and even meeting with Henry Ford in Detroit to visiting Chicago slaughterhouses, beer factories and juice manufacturers.

Mikoyan did not return to Russia empty-handed. Elements of his trip later influenced his department’s state-issued “Book of Tasty and Healthy Food.” This part-cooking manual and part-propagandist tome would become deeply entrenched in Soviet life (despite the fact a majority of its ingredients were rarely available to the general public). Since its first publication in 1939, it would be regularly updated and go on to sell over eight million copies, its pages wooing many a Soviet housewife with a lifestyle she could assume was shortly within her reach.

Among the pages of the book, which includes directives on setting the table, entertaining guests and even suggested weekly menus, are the remnants of Mikoyan’s American grand tour. Most notably, kotleti, the Russian iteration of Mikoyan’s favorite find: the hamburger. Impressed by the volume with which they could be grilled and served, Mikoyan bought 22 American hamburger-making machines and intended to replicate the meal in Russia. World War II cut his dreams short, however, and the Mikoyan Meat Processing Plant forwent the bun and has since been known for the small, oval-shaped, processed meat patty, the kotleta.

In Chicago, Mikoyan was introduced to bologna and other thick, encased boiled sausages when he toured the city’s meat-processing facilities. These became “doctor’s sausage” (doktorskaya kolbasa) in Russia, with less fat than the American version and meant to provide a high quality, nutrient-dense — i.e.: “Doctor-recommended” — everyday staple. These are still eaten and much-adored to this day.

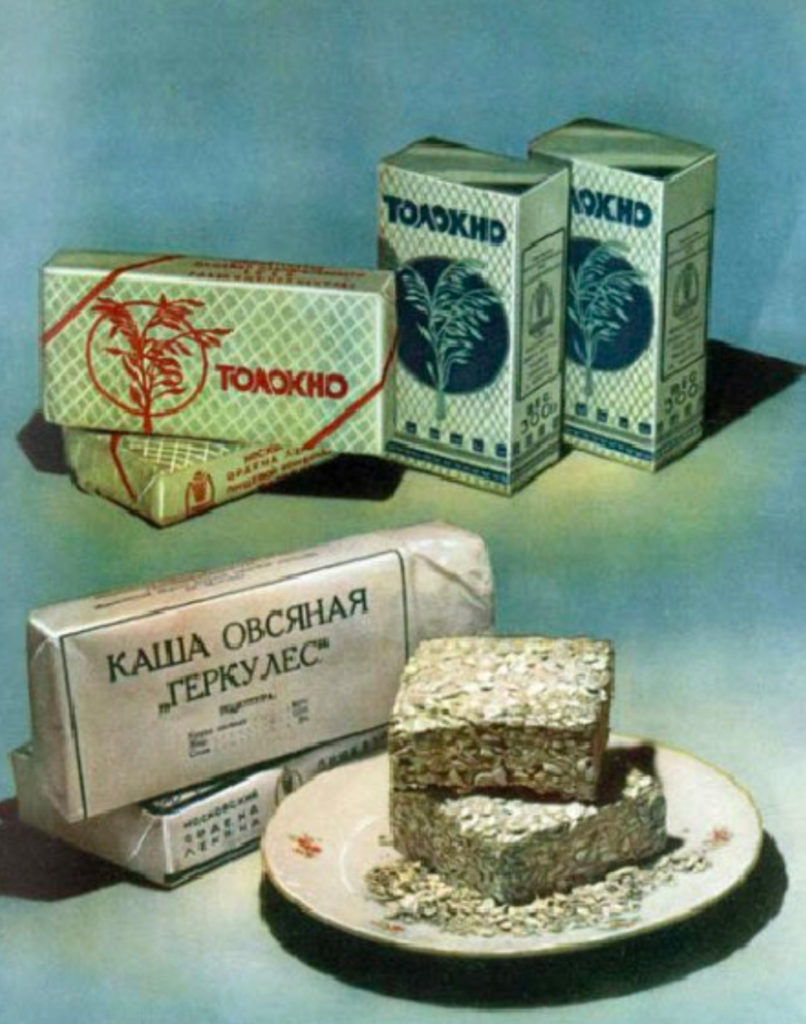

Praised in the “Book of Tasty and Healthy Food” because they don’t require cooking, contain many nutrients and minerals, and are “made from top grades of corn,” Mikoyan discovered kornfleks along with other breakfast cereals and “popped grains” (popcorn) during his trip. This was also where he was introduced to the idea of pre-packaged foods.

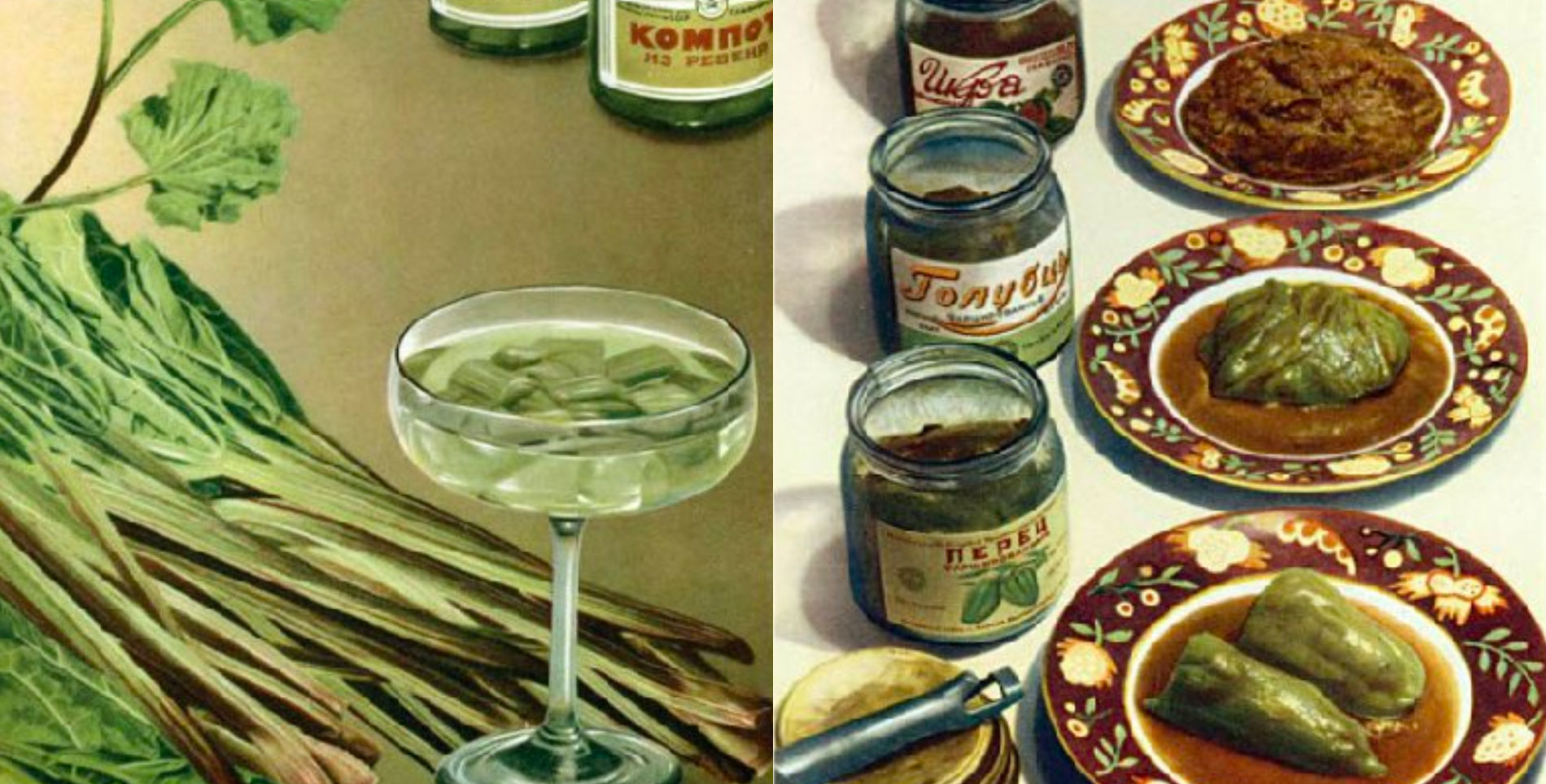

Mikoyan also loved the idea of drinking orange juice at breakfast while in the U.S. However, with Russia’s lack of fresh citrus, he decided to use the readily-available tomato instead. Today, glass jars of tomato juice are a staple in Russian kindergartens, schools, cafeterias and grocery stores, along with packaged ketchup and Russia’s most popular condiment, mayonnaise. He discovered both of these while touring U.S. food factories, and in addition to hamburger machines, Mikoyan bought and brought back industrial refrigerators and conveyor belts to replicate ice cream, tinned meats, condensed milk and canned vegetables.

While the “Book of Tasty and Healthy Food” isn’t the sole authority on Russian cuisine and culture, it does reflect an inflection point at a critical time in our modern world. Global powers continue to contract and expand well into the 21st century, posturing for dominance and excluding what could be viewed as “other.” As we near the centennial anniversary of Stalin’s rise to power, it’s prudent to pull back the curtain, reveal the true costs of breakneck progress, and develop a deeper understanding of the many different — and yet, similar — influences that led us here.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.