Throughout history, cookbooks have been active tools, offering their readers not only recipes but also insights into the time period and lives of their authors. The most successful have been text that impart a sense of intimacy that transcends the printed page. The following cooks accomplished all of the above and so much more. Using food to teach and heal, these strong, entrepreneurial African American women and men helped define American cooking.

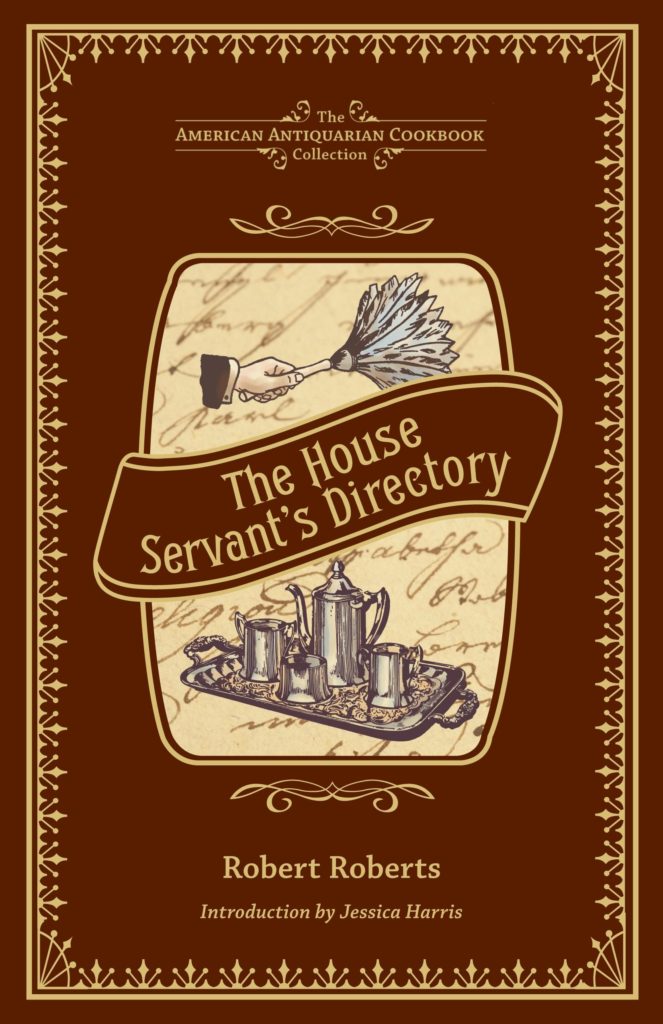

The House Servant’s Directory, or a Monitor for Private Families

By Robert Roberts, 1827

&

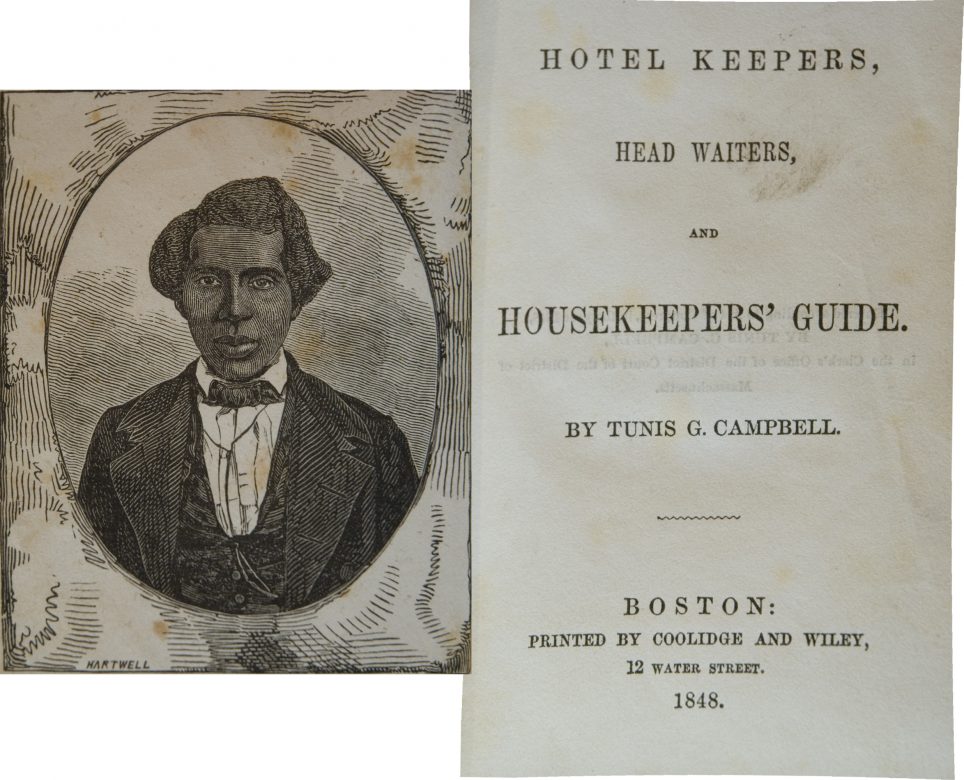

Hotel Keepers, Head Waiters, and Housekeeper’s Guide

By Tunis G. Campbell, 1848

The House Servant’s Directory was the first commercially published household management book by an African American in the United States. Written for butlers and waiters in 1827, Robert Roberts, a prominent member of Boston’s African American community, provides insights and account of what was expected of domestic servants.

In his book, Roberts includes instructions for cleaning furniture and managing a servant’s work schedule. He discusses tips for cleanliness and behavior, rules on buying, preparing and serving food and drink, and even remedies for bad breath. He provides young black men codes that would help them advance in a white-dominated world.

Before writing his book, Roberts worked as a butler for governors and senators in Massachusetts. In later years he became active in abolitionist politics and supported equal rights in education for children of all races. He died in 1860 just before the Civil War.

Twenty years after The House Servant’s Directory was published, Tunis G. Campbell wrote Hotel Keepers, Head Waiters, and Housekeeper’s Guide. Published in Boston in 1848, Campbell’s book honors the tradition launched by Roberts of helping African Americans succeed in the service industry. He insists that readers recognize the dignity of their labor and the need to be educated, well paid, prompt and clean.

Born in New Jersey in 1812 and educated in an all-white Episcopal school in Long Island, Campbell became a head-waiter, baker and preacher, and like Roberts before him, an abolitionist and cookbook author. While he worked as a hotel steward in New York City and Boston, Campbell preached against slavery. Described by white employers as a man of elevated character, the author of Hotel Keepers, Head Waiters, and Housekeeper’s Guide published his work with support from the owners of the Howard’s Hotel in New York and the Adams House Hotel in Boston.

Although household management tips fill much of the book (Campbell favored a military style of organization, instructing waiters to “hold themselves erect”), more than half consists of recipes for the European-style dishes served in early American hotels. Campbell’s instructionals include carefully detailed proportions, preceding Fannie Farmer—the queen of the level measurements—by almost fifty years.

Before the Civil War, Campbell became partner in a New York City bakery and participated in anti-slavery movements, often sharing the stage with writer and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. A dynamic personality, Campbell moved to the South where he worked to register voters and was appointed to supervise land claims, secure land titles, and rebuild schools and churches. As a member of the Georgia legislature, he protected freed people from white abusers and headed a three hundred-strong African American militia against the Ku Klux Klan. Campbell pushed for laws for equal education, integrated jury boxes, access to public facilities, and fair voting procedures.

In the Philadelphia Negro, W. E. B. Du Bois praised the African American caterers of the 1840s who “aided the Abolition cause to no little degree.” Although both Robert Roberts and Tunis G. Campbell began their careers as servants, they led their community toward literal and metaphorical liberation.

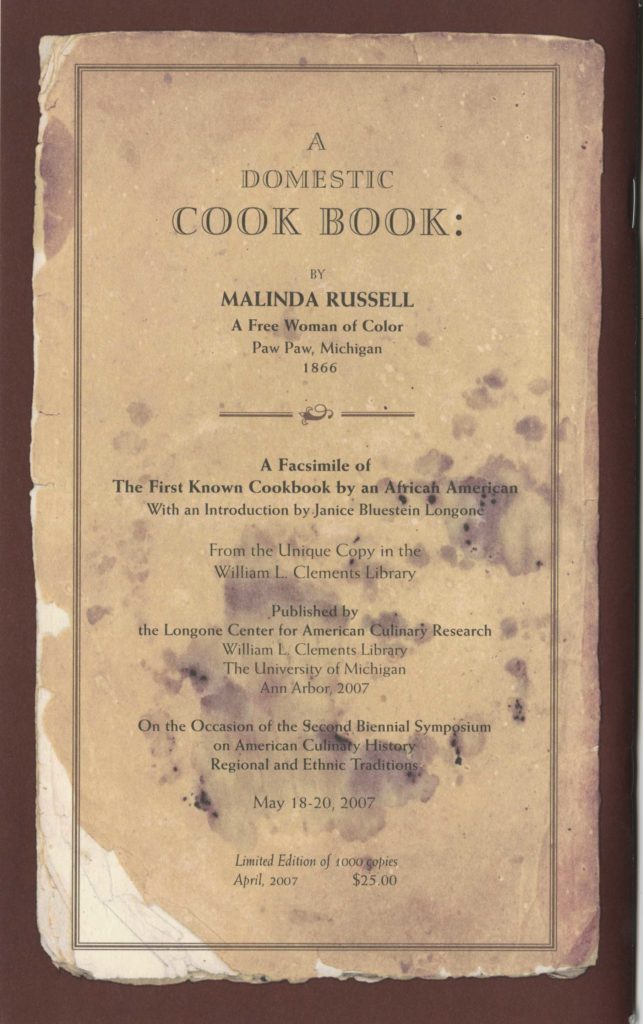

A Domestic Cook Book: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen

By Malinda Russell, 1866

Malinda Russell’s 1866 publication, A Domestic Cook Book, is a historical treasure as much for its recipes as for its insight into the lives of free African Americans after the Civil War. Published in Paw Paw, Michigan, her first-person introduction reveals she was a second-generation free black woman, born and raised in eastern Tennessee—her family being among the first set free by a Mr. Noddie of Virginia. Although freedom was her birthright, she experienced more than her fair share of pain and hardship as a free black person in the South during the Civil War.

At various stages of her life she owned a laundry business, served as a nurse/travel companion, and ran a boarding house and a successful pastry shop. “By hard labor and economy, I saved a considerable sum of money for the support of myself and my son,” she wrote in her book’s introduction. She attributed her cooking skills to Fannie Steward, a fellow cook, and to Mary Randolph’s 1824 cookbook, The Virginia Housewife.

Discovered in 2000 by antiquarian book collector Jan Longone, curator of American culinary history at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, A Domestic Cook Book is believed to be the first cookbook by an African American woman. Throughout its slim thirty-nine pages, Russell reveals that Southern cuisine was complex, cosmopolitan, and inspired by European cuisine. Elegant cakes and pastries and delicate sweet and savory custards appear alongside familiar Southern dishes like sweet potato pudding and chow chow, a traditional pickled relish adapted from the previous century’s English cookbooks, popular in the United States at the time. Russell was a black cook two generations removed from the plantation kitchen.

Russell concluded her autobiographical introduction with confidence, stating: “I know my book will sell well where I have cooked, and am sure that those using my receipts will be well satisfied.”

The year her cookbook was printed, a fire destroyed much of the tiny town of Paw Paw, leaving no trace of Russell. Her cookbook, however, lives on and has been an inspiration to countless African American women in the kitchen.

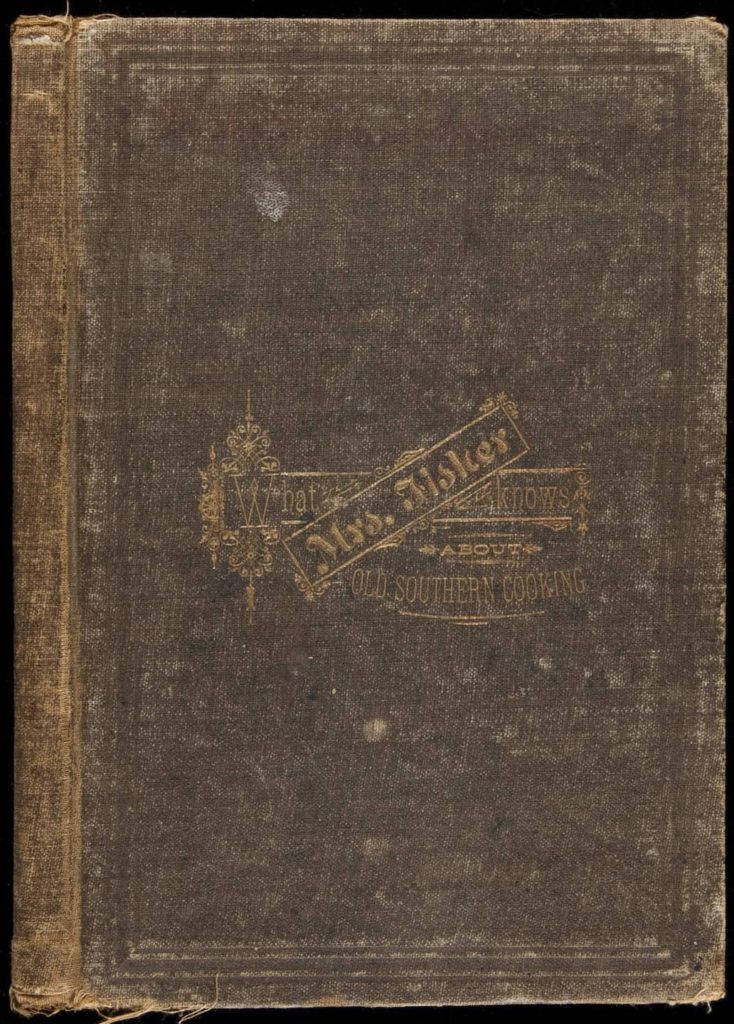

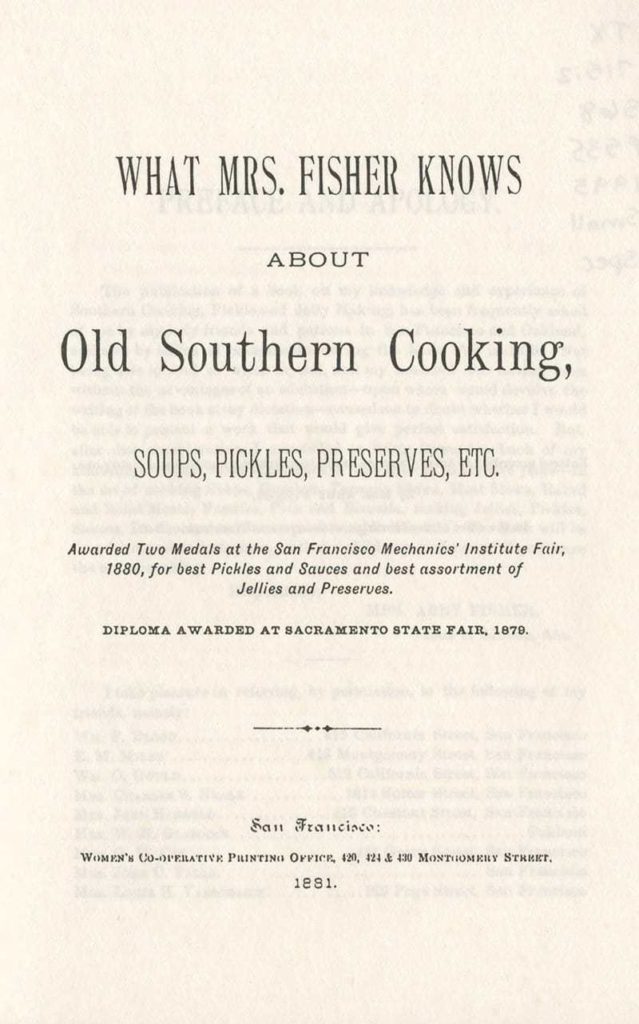

What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc.

By Abby Fisher, 1881

Until the discovery of Malinda Russell’s work, Abby Fisher’s What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc., of 1881 was considered the earliest black-authored cookbook.

Born a slave in 1832, Fisher learned to cook in South Carolina plantation kitchens. After the Civil War, she and her husband moved to Mobile, Alabama, before relocating to San Francisco in 1877. It was in this sophisticated Northern California city where she gained a reputation for her cooking skills, winning medals and diplomas at various state fairs for her pickles, relishes and sauces. Fisher’s unique flavors blended African and American cultures by combining the foods and spices from two continents. Her dishes represented some of the best Southern cooking of the day, although her distinctive combinations may have also come from her exposure to West Coast recipes including those of the Asian American population.

A sought-after cook and caterer among the San Francisco’s upper class, Fisher’s success enabled her and her husband to open their own business, Mrs. Abby Fisher & Company, and later Mrs. Abby Fisher, Pickle Manufacturer. Friends and patrons insisted she record her knowledge and experience of Southern cooking in a cookbook, but there was a hitch in that plan. Because it was illegal for slaves to learn to read and write, the wildly successful Fisher was illiterate. Therefore, her recipes had to be written down by others as she dictated. Hence, the recipe for Circuit Hash could be a misunderstanding of Succotash.

Fisher also shares a personal glimpse into her previous plantation life at times, for example in her recipe for Blackberry Syrup for Dysentery in Children, stating the tried and true syrup is “an old Southern plantation remedy among colored people.”

Published in San Francisco by the Women’s Cooperative Printing Office, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking reflects the high degree of trust on behalf of Fisher and the generosity of the people who helped her.

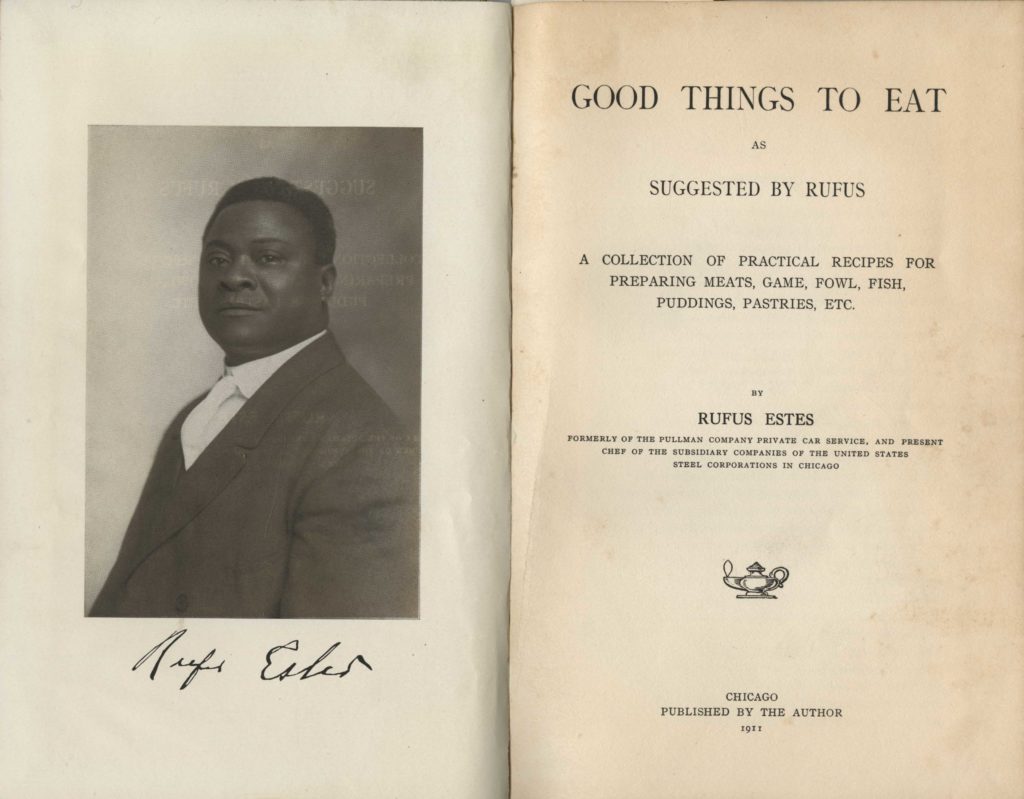

Good Things to Eat, as Suggested by Rufus: A Collection of Practical Recipes for Preparing Meats, Game, Fowl, Fish, Puddings, Pastries, Etc.

By Rufus Estes, 1911

Slave-born Rufus Estes became one of the best-known chefs in Chicago. A renowned chef for the Pullman Railway Car Service, he was first black railway chef to publish a cookbook, 1911’s Good Things to Eat.

In his introduction, Estes offers a glimpse of American history in the explanation of his name. Born in rural Tennessee in 1857, his last name comes from D.J. Estes, his slave master. History continues as he tells the reader that after emancipation, his family moved to Nashville where he briefly attended school and worked various odd jobs, including milking cows for two dollars a month. At age sixteen he began training in a Nashville restaurant before relocating to Chicago to work for the Pullman Co. in 1883.

After starting his career as a private car attendant, Estes quickly worked his way into the kitchen of the opulent railway company. Becoming a chef in the VIP dining car was quite a feat considering dining-car chefs were primarily white. In the railway hierarchy, working one’s way to a higher position was nearly impossible for African Americans who typically served as attendants, maids, porters, waiters and valets. But eventually, Estes’ culinary skills were celebrated among the upper classes of the Gilded Age.

In Good Things to Eat, Rufus explains that its nearly six hundred recipes “represent the labor of years…day by day and month by month, under…in many instances, not too favorable conditions.” His small railway kitchen was likely hot and cramped, but the working conditions did not keep him from creating extravagant dishes in addition to comfort food. Pickles and preserves give a nod to his rural Southern roots and sit right at home beside recipes for lobster bisque and steak with bordeaux sauce and bone marrow. His menus were defined by the train’s route, and his cooking was European-inspired infused with American regional ingredients. Industry magnates, American presidents, foreign dignitaries, and celebrities enjoyed his lavish meals.

Estes left Pullman in 1907 to work for U.S. Steel Corporation in Chicago, which was his place of employment when he wrote his cookbook. When Good Things to Eat was published, the Chicago Defender, the city’s African American newspaper, lauded Estes as a master of his craft. Sadly, Estes died in relative obscurity, but not before gracing the world with his culinary skills.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.