A Look Into What Sustains the Multiverse of Michelle Zauner

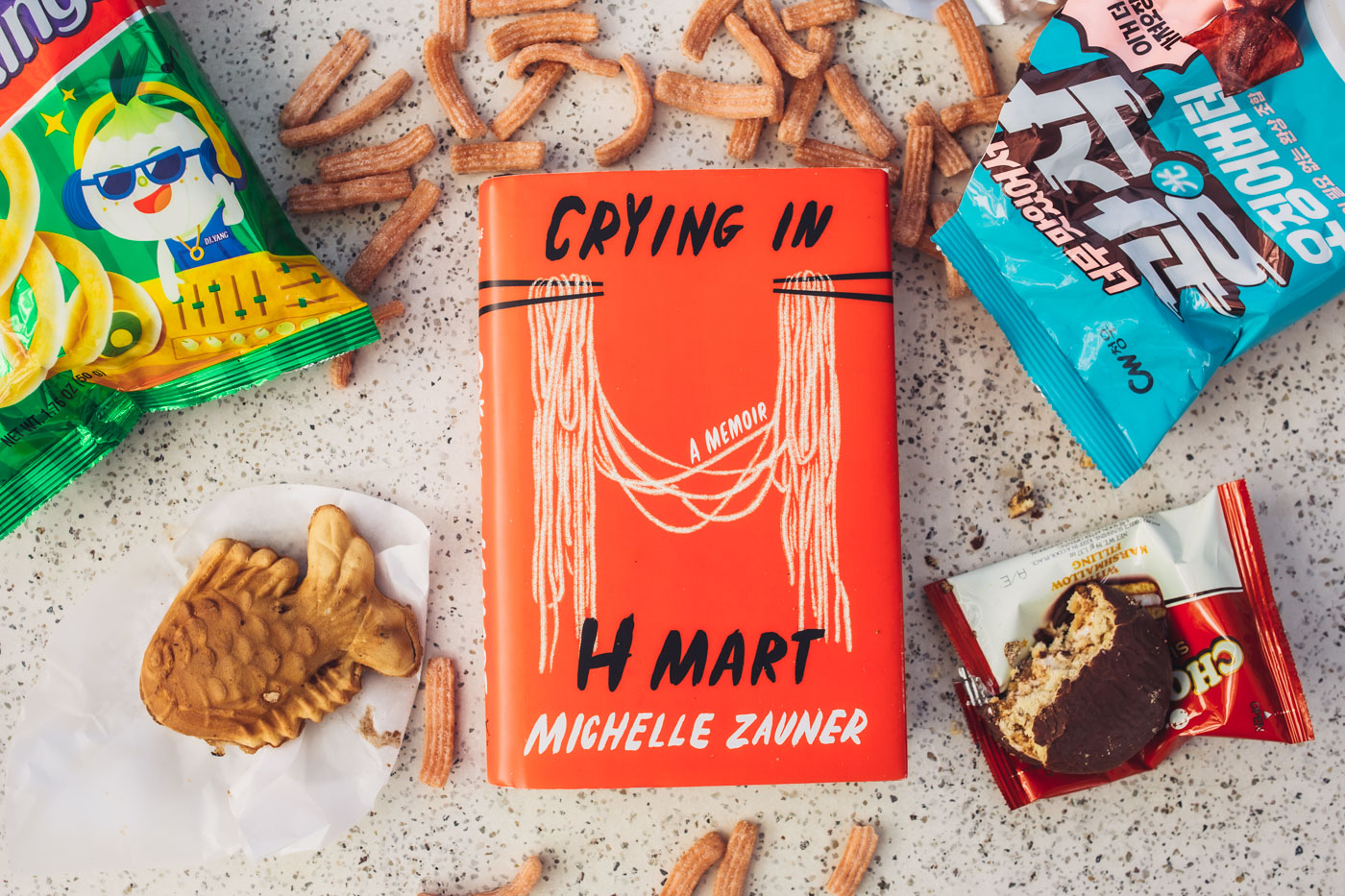

Michelle Zauner of Japanese Breakfast and best-selling author of Crying in H Mart searches for a sense of home through food.

While moving to Bryn Mawr College, almost 3,000 miles from where she grew up in Eugene, Oregon, the now-frontwoman of Japanese Breakfast, Michelle Zauner, and her parents stopped at H Mart in Upper Darby. This location is part of a strip mall of sorts, currently nestled between Rodeo Karaoke and Mia Financial, and just a handful of feet from the train tracks. The red awnings and backlit signage stand out against the beige two-story building, with double doors in the center that lead to an expanse of groceries on the first floor and a food court on the second. This was the first H Mart Zauner had ever been to, and the memories of that day, and her mother, Chongmi, still reside with her.

Zauner can still picture Chongmi’s palpable excitement walking through the aisles that day. “My mom would just be like, so pumped, you know? She would see all this stuff that our local Asian store didn’t have. It was just bigger,” Zauner says. “For her, it was really exciting because she couldn’t find a lot of that stuff unless we went to Korea.”

At H Mart, Korean food exists without having to constantly assert its prevalence at stores that by default prioritize their shelf space for foods deemed to be “mainstream,” which is generally a signifier for “white.” It offers a place outside of American grocery chains that use the word “ethnic” to reduce the foods of an entire culture to a space not more than a few feet wide, often hidden at the edge of a single aisle.

Ganjang and gochugaru reside comfortably on the shelves, with kimchi and other banchan refrigerated in their respective sections just around the corner, and a selection of fresh meat and seafood ready to become bulgogi or maeuntang is steps away. There are entire aisles devoted solely to snacks like Orion Choco Pie, Samyang Chang Gu and Nongshim Onion Flavored Rings, and practically a library of instant noodle selections ranging from Samyang Buldak to Chapagetti. In the produce section, fruits and vegetables are stacked neatly in rectangular pyramids, with enough varieties of each item that you’d be hard-pressed to taste them all, try as you might.

With H Mart just a few miles away from Bryn Mawr, Zauner remembers thinking, “I’m moving to this new city, it has a really big Asian market, I’m going to be okay.” She recalls her mother stocking up on Shin Ramyun, Zauner’s favorite, as well as microwaveable rice and seaweed to send to school with her. “It was my mom’s way of being like, ‘take care,’ you know?” Zauner says.

As an only child, Zauner thinks she always knew the day would come when there would be a parent-child role reversal and she would, in turn, come to care for her mother—but it wasn’t supposed to come when she was only 25.

In Crying in H Mart, Zauner’s first book released in April of 2021, which quickly became a New York Times Best Seller and is now slated to become a feature film, she writes of her post-college years living in Pennsylvania. She was playing guitar and singing in Little Big League while juggling three part-time jobs when she found out about her mother’s diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, which tragically turned out to be stage IV squamous cell carcinoma. So Zauner went back to Eugene, taking on the impossible task of sustaining the life of someone whose remaining time had already been spoken for.

“I really wanted to rise to the occasion, [but] I had no idea it was going to happen so soon,” she says. “Then when I wasn’t able to perform this very important task well, and it was sort of taken over, I think I felt a lot of guilt about it.”

“So much of the book and why I turned to Korean cooking was my sort of psychological undoing of that sense of failure,” Zauner continues. “It was extremely difficult, and a really horrifying part of that process was I just was so worried that my mom was going to disappear or starve to death.”

Zauner remembers losing weight during Chongmi’s illness, remarking that her family just, “…withered away.” Her relationship to food became tenuous, and with her mother’s recipes often not recorded, and Zauner not having the chance to learn them before her passing, the exact preparations were lost with her. It was a Google search for doenjang jjigae that introduced Zauner to Maangchi and her recipes.

“It became like an alternative type of therapy. Her accent was very familiar to me and it brought me great comfort,” Zauner says. “It was something I didn’t hear in my life anymore—it was like my mom’s voice in the same kind of accent.”

Zauner isn’t sure if Emily Kim, commonly known as Maangchi, knows exactly how much of a role she’s played in so many lives. In 2007, the now-64-year-old posted her first cooking demonstration on YouTube, titled “Stir-fried squid dish (Ojingeo-bokkeum: 오징어볶음).” The video opens with a song that sounds like it would be on the soundtrack for The O.C., and shows Kim preparing squid in a brightly-lit kitchen, with the camera following her around the room while she methodically demonstrates and describes each step.

Today, this video has over 470,000 views and has been followed by over 75 videos, plus a website that reads like an encyclopedia for Korean cooking. Maangchi has been hailed as the internet’s Korean mother by The Verge, as well as YouTube’s Korean Julia Child by The New York Times.

“I’m sure it started off as pretty innocent instructional videos,” Zauner says. “And now she’s so many people’s surrogate mother, godmother—you know what I mean?”

Still, Zauner feels she’s never been able to truly prepare dishes the way her mother once did. It may be a matter of ingredients or the hands that are cooking, and she’s gotten close with the kimchi jjigae, but a true replication of Chongmi’s kalbi has continued to elude her. She craves ganjang gejang, a dish she’s never been able to find prepared well in the United States, except for in Hawaii, but the dish has never come to fruition in her own kitchen.

In writing a book in which food became a character of its own, Zauner reached for dishes that represented significant moments in time for her, like jatjuk or kongguksu. For a memoir, food presents an entirely unique opportunity to re-experience a memory in some ways. “For writing a lot about these different foods, I was able to kind of recreate them or re-eat them and describe them … I mean, there are certain dishes that just stay with you that are your favorites, and then there are certain things that kind of represent something,” Zauner says.

There’s an urgency in her voice when Zauner mentions the preservation of these food traditions. “It feels really weird when something’s been such a huge part of your life for so long, and then if you don’t keep up with it, there’s not another person in your life that’s going to keep that around,” she explains. “If I want to have it in my life, then I have to go to Korea. I have to study Korean. I have to keep up with my relatives and make these dishes.”

Though Zauner was born in Korea, her family moved to Eugene when she was only nine months old. “To call myself a tourist, it feels harsh,” she says. “But I kind of feel like I’m rediscovering that country in a big way, and my sense of belonging there is so different than it used to be.” She returned for periodic visits with family while growing up, but mainly visited Seoul. “I feel like I have to forge my own connection to it, which is simultaneously exciting and also really heartbreaking,” she continues.

Touring with Japanese Breakfast has allowed Zauner the opportunity to return to the country in a different capacity. She’s developed a new relationship with her aunt Nami and, and her husband, Mr. Kim, or as she refers to him in Crying in H Mart, Emo Boo, that she describes as “really beautiful.” Zauner is turning over the idea of spending a year in Korea, noting she doesn’t feel she’ll really have that sense of belonging until she does.

But for now, Zauner is on the precipice of heading back out on tour again with Japanese Breakfast after a year that brought the music industry to a standstill and had the world questioning the existential future of venues and live music as a whole. “Everyone’s so ready to see live music again,” Zauner says. She talks excitedly about the tour, mentioning they’re going to have a lighting designer and at least a six-person band, including saxophone and violin, to create, “really lush, big arrangements.”

“I think it’s just going to be spectacular,” she says, with anticipation clinging to each word. “It’s going to be a very hopefully joyful time.”

Spectacular is a fitting description for Japanese Breakfast’s third album, Jubilee. It’s a stark contrast from Psychopomp and Soft Sounds from Another Planet, which are both admittedly melancholic—with the first named after those who guide the souls of the dead and the latter feeling like a soundtrack for a disassociation spell.

Jubilee opens with a rising orchestral tone on “Paprika” that feels like the opening of a concerto. It’s somehow larger than the space it occupies on the track, yet Zauner’s voice rings clear as she asks, “How’s it feel to be at the center of magic, to linger in tones and words?” “Be Sweet” has the sensibilities of 1980s Talking Heads, while “Kokomo, IN” hits breezy notes that sound like they are meant to be heard with a side of salty air. The record concludes with “Posing For Cars,” a track that builds from nearly a whisper into an overture as the voice of each instrument comes together in a way that feels like the end of Ragnar Kjartansson’s “The Visitors.”

Zauner is on the cover of Jubilee surrounded by dangling persimmons reminiscent of the drying preparation that results in hoshigaki or gotgam. “That whole process takes a hard bitter unpalatable fruit, and time passes and it matures into something sweet,” Zauner says. “I felt, as someone with this narrative of writing about grief and loss and more bitter topics, embracing the sweeter side of life—embracing joy—was a fitting metaphor.”

Jubilee is another entry in the multiverse of Michelle Zauner that extends through her music with Japanese Breakfast and other projects, as well as with Crying in H Mart and beyond. With each artform in conversation with one another, they lend an opportunity for deeper understanding of each other. “Music is just more about pure feeling in a way,” Zauner says. She remarks that in Crying in H Mart, Japanese Breakfast lines have been expanded into full scenes.

The almost five-year process of working on Crying in H Mart, which began before she published the first chapter in The New Yorker, has been cathartic for Zauner. She’s come to find forgiveness for herself, and others she once harbored anger toward, and rediscovered a love of food that she lost during Chongmi’s illness.

“I think grief is something that I will live with forever,” Zauner says. “I do feel like I’ve been able to say everything I wanted to say about that experience with this book and let a large portion of it go in a way.”

Even so, she was surprised at the degree of release she felt with the book’s publishing, and has been moved by the response to it. “One of my favorite pieces is finding people who’ve had tough relationships with critical immigrant parents—finding some of their relationship in that and wanting to learn how to understand their own relationships better,” Zauner says. “I’ve been really loving that people feel there’s this very nuanced kind of love and connection between immigrant parents and their kids that hasn’t been explored before … I just set out to tell my story, and it’s been really nice to see so many people have this experience, because you can feel so alone in it.”

Zauner feels as though she’s gotten to understand Chongmi in a different way through writing about her. “I feel like I was able to also examine my mother’s character in such great depth,” Zauner says. “And I feel like I learned a lot about her and was also able to have a better understanding of our relationship.”

When Zauner thinks of Chongmi now, she thinks of the kalbi that usually welcomed her home from college and came to represent a home-cooked meal for her, served alongside a selection of banchan including dongchimi, that was prepared with red pepper flakes, sesame seeds and sesame oil. “That combination of foods always really reminds me of my mom and the way that she kind of expressed love and took care of me,” she says. Zauner can even still taste the rice from Chongmi’s rice cooker that was a revelation in contrast to the microwaveable rice she’d been subsisting off of at college. “I remember the individual kernels,” she says. “The texture was so different. I missed that so much.”

Zauner has preserved a memory of Chongmi that’s not one of a woman in the grips of cancer, but something far more intimate. “I remember my mom’s skin was always kind of cold and sticky because she wore a lot of creams and stuff like that,” Zauner says. “Weirdly, that’s what I remember of my mom the most—just her, the feeling of her face.”

Cover image by Tonje Thilesen

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.