From frijoles de la olla, to rajma masala, to cassoulet, beans are an essential ingredient in countless cuisines around the world and have been since bean plants were first domesticated approximately 8,000 years ago in Mesoamerica and in the Andes. As beans traveled the globe from their places of origin, they adapted to different climates and cultures under the influence of innumerable farmers, creating the hundreds of bean varieties currently in existence.

While most commercial bean producers collectively cultivate just a handful of varieties that have been selected in recent decades for their high yield, smallholder farmers grow a much more diverse assortment of beans that have been chosen over centuries for other qualities, such as flavor or ability to thrive in an ecosystem where certain resources are limited. We honor the value embedded within the beans preserved by these farmers over many generations and growing seasons by calling them “heirlooms.”

Beans belong to the Fabaceae family of plants and many well-loved heirloom beans fall within the genus Phaseolus, which can be divided into four main types: Phaseolus acutifolius, Phaseolus coccineus, Phaseolus lunatus and Phaseolus vulgaris. However, it is not necessary to memorize Latin names to appreciate the beauty and diversity of heirloom beans, nor is it necessary to buy complicated kitchen equipment to enjoy them at home.

Steve Sando tasted his first heirloom bean about 20 years ago. The experience led him to found Rancho Gordo, which today grows, imports and sells around 35 varieties of heirloom beans. To learn about a few of these varieties and how to cook them, we spoke with Sando at the Rancho Gordo retail space in Napa, California.

Brown Tepary

Phaseolus acutifolius

The tepary bean is considered the only bean indigenous to North America—specifically Northern Mexico and the American Southwest—and has been in the care of the Tohono O’odham people for hundreds of years. Packed with protein and fiber and able to grow with very little water, the tepary has long been a vital source of nutrients for communities living in regions impacted by drought and could become more widely depended upon in a future world where population growth and climate change leave water resources increasingly strained.

Teparies are some of the smallest heirloom beans and can be found in various shades of tan, black and white. The darker teparies, such as the brown tepary, tend to have a more savory flavor in comparison to the sweeter, lighter varieties.

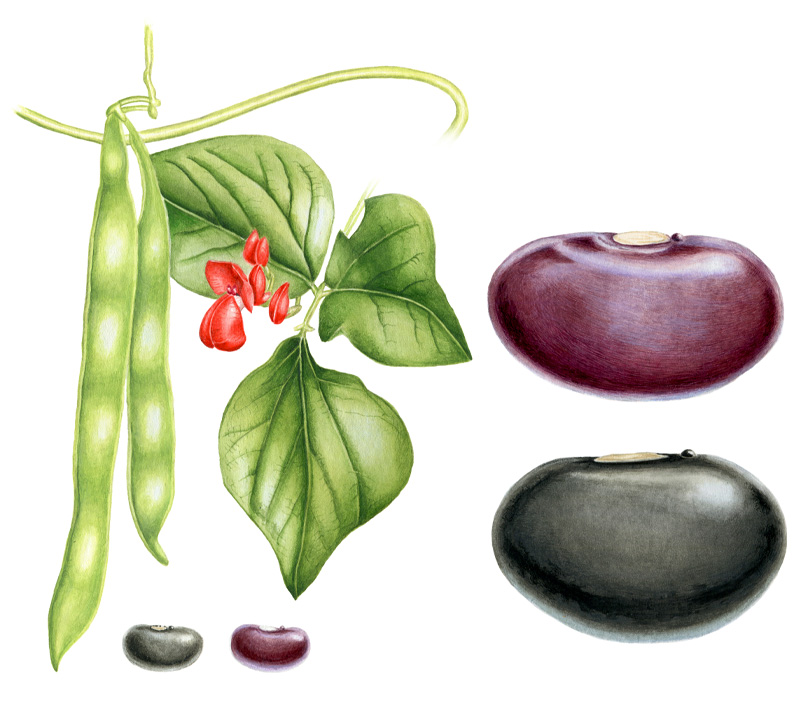

Ayocote Negro

Phaseolus coccineus

Inky black and oval in shape, the runner bean called Ayocote Negro originated in Oaxaca and is one of about 10 heirloom beans (the number varies from season to season depending on growing conditions) that are part of the Rancho Gordo-Xoxoc Project, which Sando established to help small farmers continue to grow indigenous crops in Mexico.

The Ayocote family of beans, including the white (Ayocote Blanco) and purple (Ayocote Morado) varieties offered at Rancho Gordo, was one of the first crops domesticated in the New World and is well adapted to growing in a dry environment. Sando explains, “Where we grow our Ayocote, there’s no irrigation. It’s amazing because there’s this awful rocky field that we wouldn’t even consider growing in, and they actually take the rocks and use them to cover around the base of the plants.” Through this inventive and laborious process, Ayocote farmers demonstrate how to produce food from even the most challenging of landscapes.

Christmas Lima

Phaseolus lunatus

Named for its festive red and white speckled appearance, the Christmas lima is also known in some parts of the world as the chestnut lima based on its chestnut-like texture and flavor. Though lima beans tend to have more adversaries than advocates, the Christmas lima promises to impress anyone willing to give it a chance.

Originally from Peru, these enormous beans should be cooked slow and low to yield a rich broth and a creamy bean that works well in soups, salads or simply as a side dish.

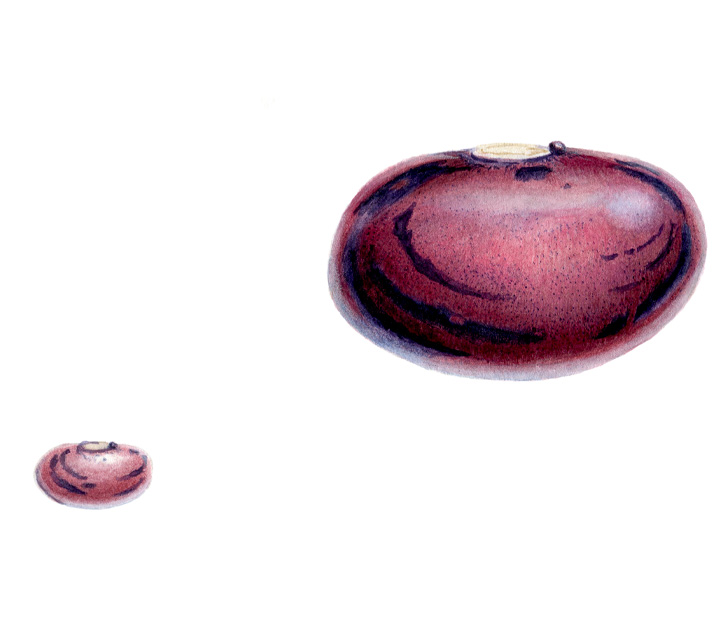

Rio Zape

Phaseolus vulgaris

The Rio Zape is the bean that started it all for Sando, the seed from which Rancho Gordo grew. Also known as the Hopi Purple String Bean, this variety shares a long history with the Hopi people of the Southwestern United States.

Though similar to the pinto beans with which many of us are familiar, Rio Zape beans have a flavor that is entirely their own, marked by notes of chocolate and coffee. Sando recommends preparing them with a squeeze of lime and chopped raw white onion.

Cooking Heirloom Beans

It takes a little courage and imagination to believe you can transform hard-as-a-rock dried beans into something edible, especially when there is so much conflicting information out there on how to go about it, but Sando’s approach to preparing heirloom beans is reassuringly simple.

To start, all dried beans should be checked for debris (such as pebbles) that may not have been detected during the packaging process, then rinsed in water. When it comes to the question of soaking the beans in a pot of water a few hours before cooking them as some recipes suggest, Sando says, “You can soak. You don’t have to soak. I don’t soak, but I wouldn’t be upset if you did. The main thing is to bring [the pot of beans] to a hard rapid boil for 10 to 15 minutes and then let it go.”

Rancho Gordo tests all of their beans by cooking them on a stovetop, in a crockpot, and in a pressure cooker. Sando observes that a clay pot is the preferred vessel for cooking beans in many cultures, but whatever you have on hand will do as long as the beans are able to simmer over low heat until they are cooked through, usually for about one to three hours depending on the variety.

While heirloom beans can hold their own in just about any kind of dish with just about any kind of meat, cheese, vegetable or spice—or even, as Sando suggests, with honey—the first time you cook with a bean, try tasting it warm with only a pinch of salt in order to fully appreciate its unique flavor.

Illustrations by Francisca Espinoza.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.