Chanchala Gunewardena was born and raised in Colombo, Sri Lanka, just a short distance northwest along the coast from where her mother grew up in Matara, which is, according to Gunewardena, “famous for its kithul”—a syrup made using sap from the fishtail palm trees that grow on the island. Traveling inland, you will find these trees in abundance in the Sinharaja Forest Reserve (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) and scattered throughout 18 of Sri Lanka’s 25 districts.

Although fishtail palm trees—commonly referred to as “kithul trees”—are indigenous to a number of Southeast Asian countries, and in India are tapped for sap that is fermented to produce alcohol (a practice that also takes place in Sri Lanka), Gunewardena points out that Sri Lankans “seem to have been unique in celebrating its sweet syrup and making it such a centerpiece of our cuisine.”

Gunewardena considers kithul “a natural food treasure that has been quietly preserved over centuries by smallholder farmers living on forest perimeters,” and describes it as “a dark-golden thickish syrup, which, to taste, promises both nuance and discovery—smoky-sweet, earthy-floral and punchy-umami.” (She notes that this last descriptor came from the 2018 “World’s 50 Best Bars” winner, mixologist Ryan Chetiyawardana, a.k.a. Mr. Lyan, who has incorporated kithul and other ingredients inspired by his Sri Lankan heritage into cocktails.)

“Dessert is its most common partner in Sri Lanka,” says Gunewardena. “My personal go-to is sliced semi-sweet bananas (Sri Lanka has so many types), freshly-grated coconut, a pinch of salt, and a healthy pour of kithul. There’s also batter-fried banana fritters with ice cream and kithul syrup, coconut milk-centered hoppers served with kithul jaggery or syrup, and wellawahum (turmeric pancakes rolled with a kithul-soaked grated coconut center).”

Although Gunewardena has enjoyed kithul her whole life, her passion for it deepened in 2017. “We were gifted an especially glorious bottle of kithul and I asked why there was such a difference to the commercially available types,” she recalls. “My ammi [mother] replied this was pure, unadulterated with sugar and water.” The experience was so significant that it led her to found Kimbula Kitchen that same year with the intention of sharing high-quality kithul with people beyond Sri Lanka’s shores.

Over the last few years, Gunewardena has “learned a broader scope of possibilities” for what she calls Sri Lanka’s “Sweet Secret of the Tropics” in seeing Kimbula Kitchen’s flagship product transformed into various sweet and savory dishes and drinks around the world, including “a kithul and tamarind Belgian beer by Dageraad Brewing in Canada; a kithul and rhubarb Manhattan made at Paradise in London; a mackerel in a kombu, shitake and kithul broth by Top Chef Australia’s Minoli De Silva; roasted carrots with kithul tossed in curry powder and melted ghee by Samantha Fore for Milk Street; a Buffalo curd, arrack, kurakkan and kithul dessert by Rishi Naleendra [the first Sri-Lankan born winner of a Michelin star] in Singapore.”

The production of pure kithul starts with the planting of a fishtail palm tree, which can take as much as 15 years to reach flowering maturity and grow up to 40 feet. The height of the tree above ground is reflected below in an extensive root system, making the trees “good for flood resilience in disaster-prone areas, giving more binding to the soil, so it’s not washed away so easily,” Gunewardena explains. Additionally, because “a mix of forest crops can be grown amicably alongside” this tree, it plays an important role in agroforestry systems on the island and many smallholder farmers (who may have just a few kithul trees on their land) “do kithul as a secondary crop to tea.”

“To secure the sap, a tapper climbs three to four times a day,” explains Gunewardena. “Unsurprisingly, many tappers have stories and scars that speak to a climb gone wrong—bamboo or other homespun ladders breaking, encountering snakes, et cetera.”

“There is definite respect between man and nature in this process and there are a lot of generational auspicious customs that are vital to tappers in doing their work as they believe these practices are what ensure their safety and the quality of the kithul,” she says. For example, “the first yield from a freshly-cut flower is reserved [with] the intention is to ward off dangers from evil spirits and give blessings.”

The kithul sap is harvested from the inflorescence of the tree—“this ‘flower’ that looks like long tendrils hanging down”—and is then boiled to a syrup over a woodfire.

At this point, the team at Kimbula Kitchen will “taste to select the best of this wild-crafted magic and then re-blend in small batches,” explains Gunewardena. The final bottled product is made of 100% pure kithul tree syrup, which is not the case for many kithul products that are instead diluted with sugar and water.

“The root cause of why the industry at large has failed to harness pure kithul and pushed forward an adulterated sugar-water stand-in instead is that the product is hard-won and low-yield,” Gunewardena explains. “And our national approach was trying to make ourselves similar at scale to other products—maple, in particular—rather than embrace the difference.”

“As is true of many crops, suppliers from our side of the world felt we didn’t have much voice and leverage at the bargaining table with buyers, so the sacrifices made on price translate down through the supply chain to product and farmer,” says Gunewardena, which results in kithul of inferior quality and meager earnings for producers.

Gunewardena has built close relationships with smallholder kithul farmers and is guided by her commitment “to do right by farmers, particularly on pay,” which “includes paying not just the competitive market price, but above it to our farmers.”

These farmers are independent and not employed by Kimbula Kitchen, but often collaborate with their team given the opportunity to receive direct payment at an above-market price. Gunewardena notes, “They can sell to whoever; they just prefer to work with us as they also know that we don’t adulterate what they tap.”

“We need growth to be able to provide them the assurance we can be their single buyer,” says Gunewardena, adding that they are working toward “a cooperative model long-term” and “investment in their communities.”

After founding Kimbula Kitchen, Gunewardena had less than two years to begin building her business before being hit with a series of unpredictable and nearly insurmountable hardships. In speaking of these hardships, Gunewardena cites the role of a prominent Sri Lankan family, the Rajapaksas, in national politics as the cause of many problems for Lankans.

“The Rajapaksa family first came into top leadership in 2005. They claimed they delivered the ‘victory’ [in 2009] in our 30-year civil war—though what is victory when your own country’s people are fighting each other?” says Gunewardena. “In the aftermath, they demonstrated no interest in peace with continued oppression of minorities and critics, which is what got us to war in the first place.”

The Rajapaksas remained in government until being voted out in 2015, but were re-elected just four years later in the wake of terrorist bombings thanks to an election campaign platform that promised to spur economic growth and pay off national debt. Gunewardena, however, claims that their actions had the opposite effect: “They scrapped taxes and immediately 25% of government revenue disappeared. The government also started printing rupees in the billions, setting up the path to terrible inflation.”

Shortly after, the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic presented an onslaught of risks and restrictions—worsened, according to Gunewardena, by government corruption—that severely impacted small businesses like Kimbula Kitchen. One year into the pandemic, those working in the agricultural sector were subjected to a new disaster in the form of a nationwide ban on chemical fertilizers following an abrupt governmental announcement in April of 2021 that Sri Lanka would be the first country to convert entirely to organic farming.

While a national transition to organic agriculture sounds good in theory, Gunewardena points out that the implementation of such a plan is much more complicated. “I think we really need to understand globally the double edge of moving toward healthier farm systems so small farmers in developing nations can actually participate,” she says. “[Transitioning to organic agriculture] takes time and must be done with great caution. I can speak to what I saw here and it was destruction of livelihoods, of badly implemented policy under the veneer of doing good. This ban [on chemical fertilizer] hit both our export crops and our local sustenance.”

Gunewardena explains that the Kimbula Kitchen team “saw the fallout of this ban early because we source from smallholders and began to wonder whether the actual intent to be the world’s first organic nation was A) to serve foreign exchange dollars on fertilizer imports, B) to create an organic fertilizer business stream for their friends, or C) push smallholders out and consolidate their land under bigger buyers. Fearing a bit of all three, we knew we had to speak up and did.”

In the days following the announcement of the ban, Sri Lankans began to protest. Gunewardena notes that “farmers were some of Sri Lanka’s first protestors.” As a result of these protests, the government declared a partial reversal of the ban about six months later in November of 2021. But the damage was already done, resulting in shortages of domestically-grown crops and a state of food insecurity on the island.

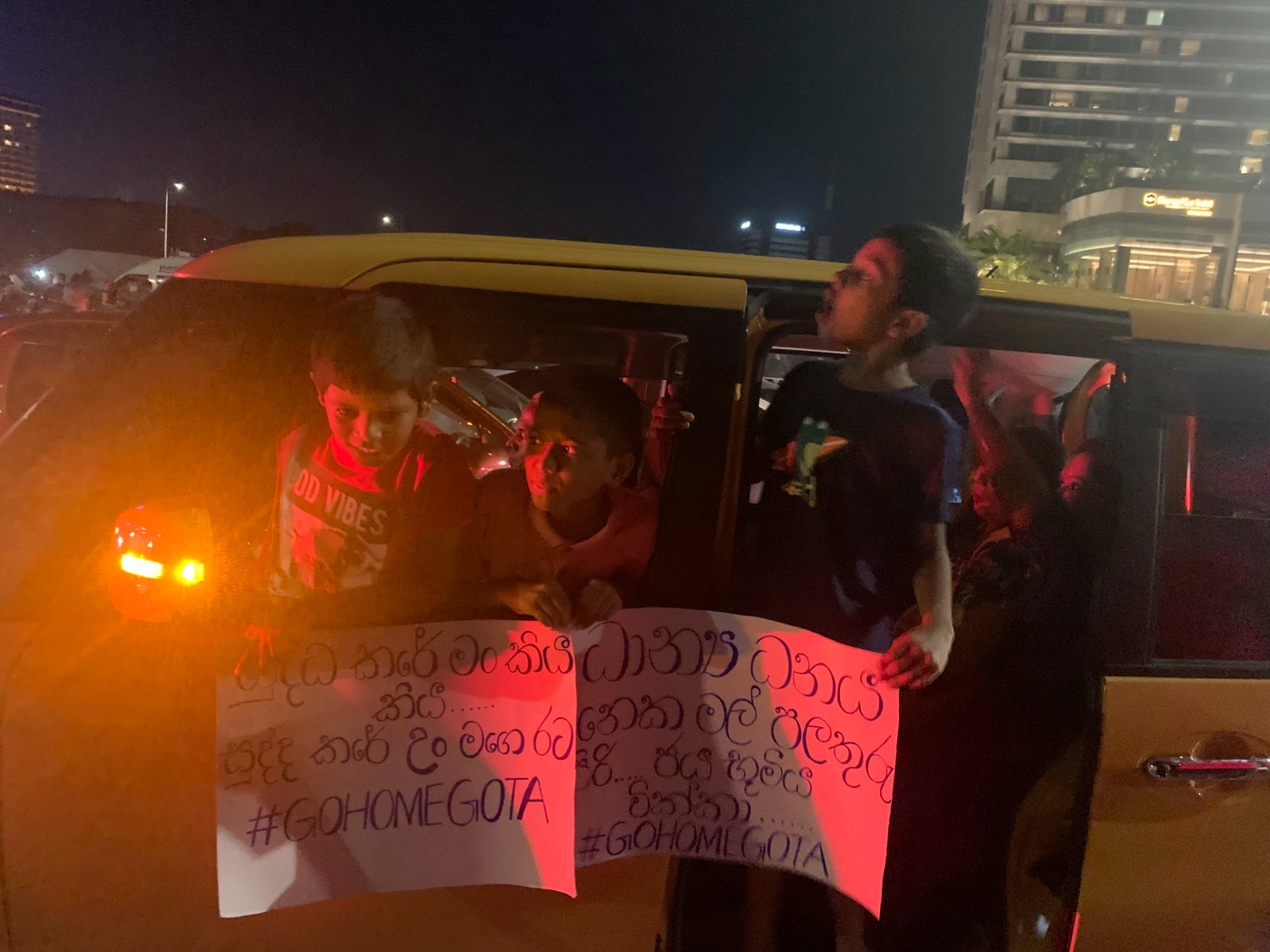

Protests in opposition of the Rajapaksa family continued into the new year as well. “The numbers ebb and flow, but the largest protests have been close to the hundreds of thousands mark, and way over 100 have taken place in all sizes across the country,” says Gunewardena. “Despite the clickbait headlines, protests have been primarily peaceful and our anger is at our government. The goal is the resignation of the Rajapaksa family from political life.”

Meanwhile, keeping Kimbula Kitchen in business is a daily struggle. “Costs are constantly rising and getting fuel for sourcing trips [to kithul farms] is uncertain and requires staff spending hours in line,” explains Gunewardena. “Freight costs have gone through the roof globally. The way we survive is with export partners who are compassionate to work with us through it.”

These many hardships, however, have only bolstered Gunewardena’s dedication to leveraging her business to help those around her. On April 9, 2022, Kimbula Kitchen announced a partnership with Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement, one of Sri Lanka’s largest and oldest islandwide community development organizations, to raise $300,000 (USD) to provide food to those in Sri Lanka who may otherwise not have sufficient sustenance at this time.

“We did our first distribution of Family Food Packs on May 18 and 19, distributing 1,000 packs to families of daily-wage earners living in the urban centers where cost of living has risen the most, and to school children and parents from under-resourced urban schools, and female workers in the urban export processing zone that also faced challenges of work limitations during Covid lockdowns,” says Gunewardena. “We are looking to do the next round as soon as there is fuel. The need is definitely there and looking like it will only grow due to upcoming harvests being low.”

Gunewardena encourages those seeking to support the people of Sri Lanka to make a donation through Sarvodaya, to hire Lankan freelancers, and to visit Sri Lanka, promising, “singular landscapes of beach, safari and forest to explore, and a people who will welcome you with the warmest hearts.”

Among the simplest and most effective ways for people around the world to make a positive contribution during this time of crisis in Sri Lanka is to buy directly from Sri Lankan brands like Kimbula Kitchen, which is currently in the process of expanding its offerings beyond kithul to work with other local ingredients.

“We believe you will discover something new to love from our wonderful island home,” says Gunewardena. “And we know we will rise out of this moment of crisis united and stronger than ever.”

Photos courtesy of Kimbula Kithul

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.