On a rainy morning during the early months of the pandemic, while standing in a short queue for my shopping, I noticed a much larger queue waiting quietly on the other side of the intersection dividing the wards of Heaton and Byker in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Those people were waiting for food too—for their turn at Newcastle’s East End Food Bank.

The pandemic is not the only factor that has forced thousands of families in the United Kingdom to turn to emergency measures. Figures from the Trussell Trust, a charity which aims to end hunger and destitution, show that in the year austerity measures were introduced in 2010, 61,468 people received three days’ worth of emergency food from its food banks.

That number has risen significantly since, and in 2019 and 2020, 1,900,122 people received such a package from the Trussell Trust. Worryingly, those figures don’t even account for three quarters of food banks in the United Kingdom as The Trussell Trust runs around 1,300 food banks, while another 900 are run independently.

This substantial increase has meant it is impossible not to notice food insecurity. In March 2021, nine out of 10 councils in the United Kingdom reported a rise in the use of food banks. Marcus Rashford, a Manchester United footballer who relied on free school meals as a child, stepped into force the U.K.’s Conservative government—who had initially refused—to supply school meals over holidays during the pandemic to prevent millions of children from going hungry.

The government’s inaction in tackling poverty not only now, but since the introduction of austerity measures, raises the question: Why are so many people facing food insecurity in the world’s sixth largest economy?

In the years since austerity measures were brought in, there are the small matters that the United Kingdom has left the European Union and what was initially the climate crisis has become the climate emergency. It’s unclear so far what effect these two factors have had on food insecurity, but some of the potential solutions to drive the numbers of people using food banks down may also be applicable to combatting the climate emergency and negotiating Britain’s exit from the European Union.

Though food banks can be a short-term solution, they are sticking plaster on an open wound made by political decisions (and indecisions) that fester, becoming more toxic by the day.

The community of Shieldfield, a ward (administrative division of a city) in the east end of Newcastle upon Tyne, has ambitious plans to combine art, activism and upskilling to fight food inequality—with a dose of the region’s history and traditions thrown in.

In December 2020, Big River Bakery, which is based in the ward, baked bread with wheat claimed to be the first grown in Newcastle upon Tyne in over 100 years. In a project jointly headed up with local gallery Shieldfield Art Works, 61 harvest packs of the locally-inspired Shieldfield Loaf were delivered to the surrounding community.

“People are a bit disconnected about where food comes from. However, there’s a slow shift of people becoming more interested in how far food has travelled and how healthy it is. I think it’s a good shift,” Lydia Hiorns, Programme Manager at Shieldfield Art Works says. “We made 10 loaves in total, which were grown, milled and baked in Shieldfield. Each person involved in the project got a slice of bread and some of the preserves that we made in our harvest packs.”

This may seem like a small amount, but it is a starting point. “It has really created a bond in the community. People are feeling that they have more of a stake in their area and what goes on,” Hiorns says. “People have become friends, and I think growing together bonds you together—especially in a pandemic.”

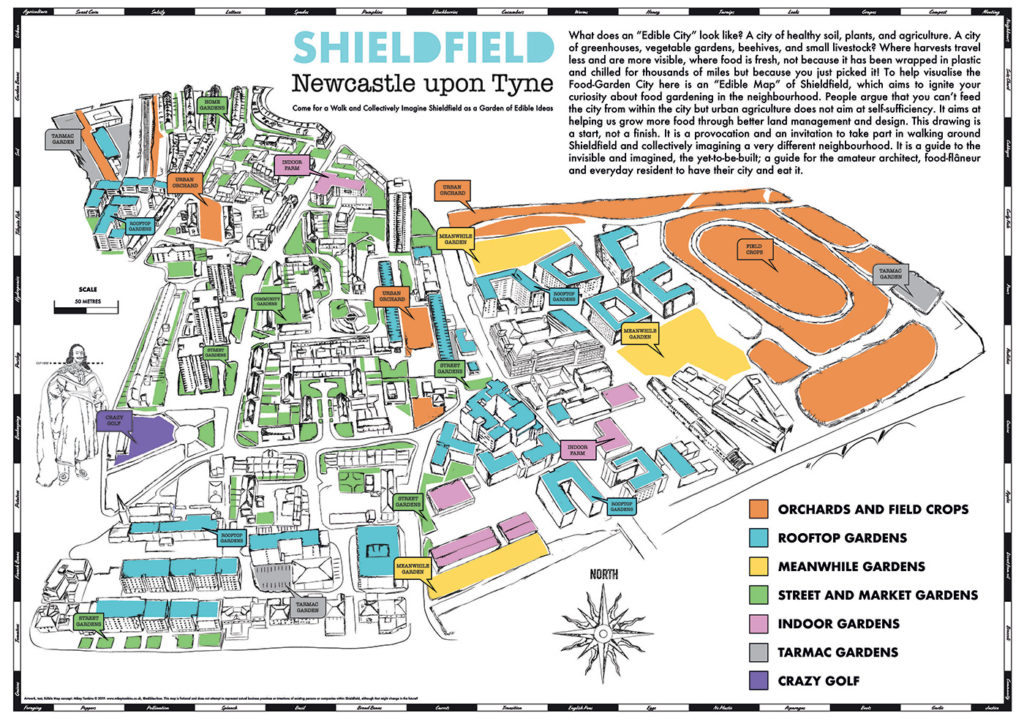

The project also included making an “edible map” of the local area, designed by artist Mikey Tomkins and displayed in Shieldfield Art Works’ gallery. In addition to where wheat was grown for the project, it shows areas which can be used for food production or where pollinators can be introduced.

Big River Bakery is where the Shieldfield Loaf is made, but its owner Andy Haddon has been aiming to shake things up since it started selling baked goods in a local library in the Tyne Valley village of Wylam, his hometown.

“Our bakery isn’t just a commercial operation. It’s about environmental impact and social impact combined with profitability,” he explains. “If that’s done well, it is possible for local food to be healthy and available to everyone—not just the affluent, which is the tendency with British local food. It’s often referred to as artisan food, which isn’t a word I particularly like. That model has to change if we want a food economy that is sustainable both environmentally and financially.”

Big River Bakery has always worked with a short supply chain, and many other food businesses in the country may need to follow suit as a result of Brexit. Around 80% of the food sold in Britain is imported, with food shortages in the early months of 2021 showing just how unsustainable that is.

“We totally need to rethink farming, and that’s for reasons ranging from Covid to Brexit,” Haddon says. “There’s a lot of really rich land in the North East of England, and it’s shocking how little of that is used for food production.”

“Our farmers are locked into a system where their share of the income is controlled by other people such as commodity traders. With a shorter supply chain, there’s the potential to share it out more equitably, meaning a lower price for the end consumer,” Haddon continues. “We’re doing that with wheat at the moment, but we want to be a real catalyst and inspire other people to take projects like ours forward with other crops.”

Haddon’s ideas are more than just idealism. Though his main project is the Big River Bakery, he has also been director at Scotland the Bread, a project in Scotland producing wheat at scale, which already does several of the things the Big River Bakery is aiming to do. And, the project in Newcastle also focuses on delivering employability programs through baking, focusing on developing people’s skills to get back into work, while building their confidence.

“We’ve done practical projects that build people’s own skills and solutions to help them move away from using food banks,” says Haddon. “Communities have got to start developing their skills and capacity to find solutions themselves, and the bakery can hopefully help move things along in that direction.”

Baking the Shieldfield Loaf was symbolic, Haddon tells me. “Covid and food poverty overlap, and affordable food has become a more important topic since the pandemic hit. However, it’s not a new one—it’s been coming back again and again over the centuries. But it’s particularly resonant at the moment.”

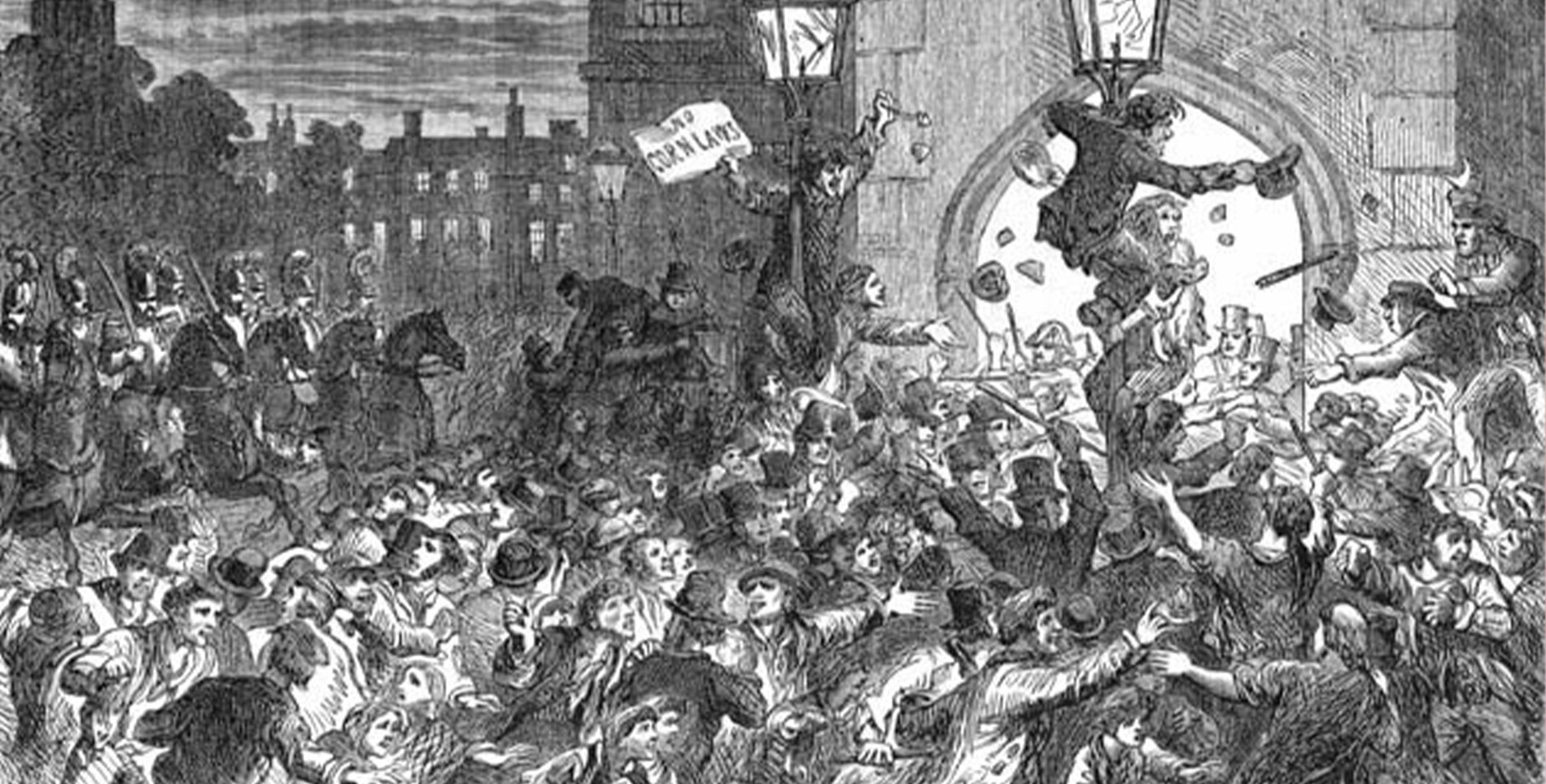

In fact, the East End of Newcastle is no stranger to food inequality. 2020 marked the 240th anniversary of the Newcastle Corn Riots. They took place in what is now the suburb of Heaton (one of Shieldfield’s neighboring wards), in what used to be primarily farmland.

In the summer of 1739, heavy rain led to a poor harvest—meaning grain was in short supply and people were starving, despite having Alderman Matthew Ridley, one of a few men who was part of a strict social hierarchy in the ward, living at the nearby stately home of Heaton Hall. At the time, there were reports of shortages in not only food, but of coal used for fuel, and even water.

It is believed that in March the following year, when local food supplies were already short, speculators hoarded grain to sell at inflated prices abroad. The price of corn, oats, and rye had all become so high that the people of Heaton couldn’t afford to feed their families.

In May 1740, a demonstration was instigated by “General” Jane Bogey, who led a small group of female protesters in Newcastle―one of many across England. It was the precursor to a much larger protest, which occurred On June 20, 1740. Things came to a head when townspeople gathered outside of Newcastle upon Tyne’s Guildhall, and while at first the protest was peaceful, the crowd of around 1,500 people rioted, resulting in at least one death.

Shoe Tree Arts identified the parallels between then and now and worked to deliver the Corn Riots Festival. Like most of the scheduled events in 2020, the festival was postponed. However, it has been rescheduled for 2021, with some events already taking place in May and more to follow this summer.

“We thought the Riots would be a good subject to build a community art project around. We wanted to pull in lots of different groups and think about agitating—who agitates, why do people riot?” Ellen Phethean, poet and member of Shoe Tree Arts, explains. “Can community action bring about change, and is it a good thing?” Phethean’s part in the festival includes delivering writing workshops and classes to anyone who is interested.

“One of my ideas is that we parallel characters from the 1740s and characters from now—a woman who’s struggling to feed her children in 1740 could parallel with a woman who is going to food banks now,” Phethean continues. “Let’s look at the political climate and think about why people get hungry and whose fault it is. Those who withhold food and aid were the same then as they are now.”

Many different issues have been brought to the fore by Covid, and they’re being highlighted by projects like those going on in Shieldfield. However, it’s clear there’s no easy answer to solve food inequality in this area. But starting small and highlighting the issue within the local community, rather than waiting for directions to come from above, could go a significant way in tackling the issue.

“What’s really needed is a proper pathway to take things forward, and I’m not sure if that has been mapped out yet,” Haddon says. “In the end, we need to rethink how we grow and distribute food. Maybe in the region we can show some leadership. If we develop projects on a grassroots scale, people can’t ignore them.”

He continues, “The North East had a driving role in the carboniferous industrial revolution, with George Stephenson (who was known as the ‘Father of Railways’ and invented the ‘Rocket’ locomotive). I hope we can have a role in the non-carboniferous revolution too.”

If this part of the country were to be the driving force behind a new food revolution? That could only lead to more positives.

The glacial pace that power structures move in the U.K. means a fairer food system is still years off. However, community and grassroots movements giving that a stir and sparking momentum can help serve as a catalyst for change. In an area with such a rich history of innovation, there are few better places to kickstart such a movement.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.