How Markets and Delis Connect Slavic Families To Their Old-World Traditions

The ready-made meals, frozen dumplings, fresh-baked bread, and other staples on offer at these West Coast markets have long histories of Soviet migration.

Editor’s Note: this story is published in partnership with KCET / PBS SoCal and in association to The Migrant Kitchen, our Emmy-winning documentary series now on its fourth season. The Migrant Kitchen stories written around Russian migration were written prior to the invasion in Ukraine. These stories examine and provide voices to the decades-long diaspora of citizens leaving and fleeing Soviet rule.

Boris Fudym grew up eating fresh herring and sturgeon hauled onto the rocky shores of his hometown, Odesa, in what is today Ukraine, from the wind-whipped waters of the Black Sea. Now, half a world away and half a century later in San Francisco, California, Fudym raves about the varieties of salted, smoked and tinned herring on offer at New World Market, a Russian market and delicatessen Fudym has frequented since he migrated to San Francisco 30 years ago and owned since its previous owners retired in 2015. “We had a deli similar to this,” he says of his childhood in Odesa. “We were accustomed to homemade food all the time because of the families and the way we grew up.”

Fudym is one of the millions of Americans who migrated to the United States from Imperial Russia or the Soviet Union as early as the 1860s. The largest waves comprised religious minority groups fleeing persecution and white émigrés, a term used to describe those who fled the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and subsequent civil war. Many more left the Soviet Union for the United States during the 20th century when regulations and relations between the two nations allowed. The descriptors “Slavic,” “Russian-speaking” or just plain “Russian” are often used to group the diverse peoples and traditions that come from this vast region which stretches across Eurasia from the Carpathian Mountains to the Bering Strait, coming so close to North America that you can see it from Alaska’s coast, itself a former possession of the Russian Empire.

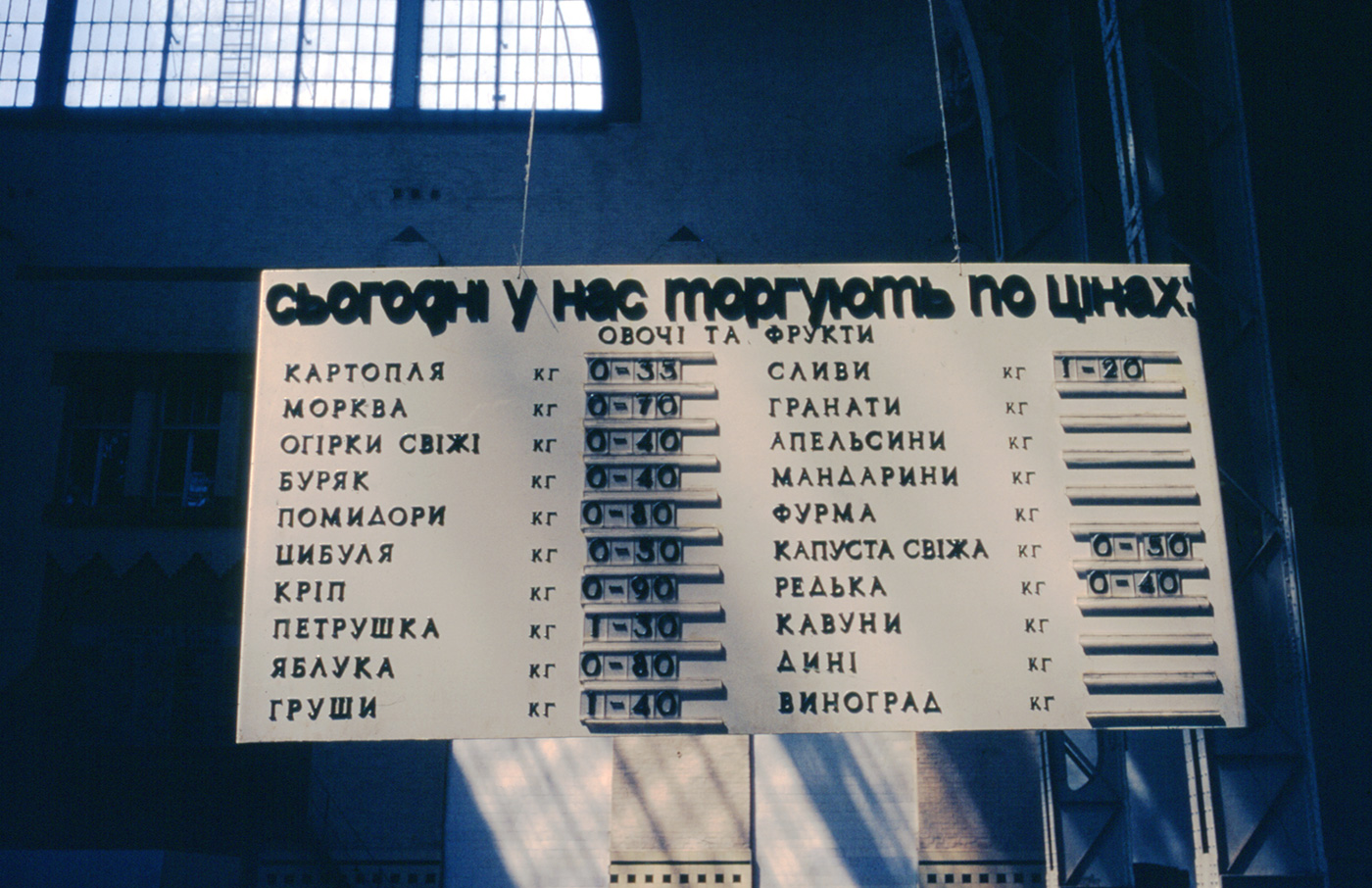

The following images are of a marketplace in Kiev, Ukraine and were photographed by Thomas Taylor Hammond in 1972 during his trip to the Soviet Union.

The majority of Slavic migrants to the United States settled on the coasts, with large populations landing in the West in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Portland. They brought their food with them. “When people move to new places and are trying to find their bearings, one of the things that is a touchstone is the food of the place that they came from,” says Darra Goldstein, a food scholar and author of several award-winning texts on Russian and Georgian histories, food and culture.

While other migrant groups like Chinese Americans carved out a place for themselves in the United States with restaurants, Slavic migrants have made a habit out of opening delis. The reason is rooted in their histories. “In Russia, the opening of restaurants wasn’t widespread,” explains Goldstein of the early 20th century and Soviet era. “It was more delis or food shops for the communities they represented, so people could go and get the foods that were important to them.”

These shops sold salads, sausages, salami and something called polufabrikat, or half-made, foods. These prepared foods included staples like ground meat cutlets and stuffed dumplings called pelmeni that could be purchased chilled or frozen, then cooked and served at home. Not the boxed fish sticks of your average supermarket frozen foods aisle, Russia’s ready-made foods were “often quite delicious,” says Goldstein. It was this tradition of delis and markets proffering prepared foods, dozens of fresh salads, wholesome breads, sweet preserves and sour pickles that Slavic immigrants rekindled in cities across the United States.

New World Market opened in this atmosphere to serve a population of Russian speakers who settled in San Francisco’s Richmond District and were looking for a taste of home. Its location on Geary Boulevard is at the heart of an enclave now known as Little Russia. From its entrance, the bulbous golden domes of San Francisco’s oldest Russian Orthodox cathedral can be seen rising above white arches trimmed in burgundy and seafoam green. “That [area] became this important core community of the Russians of San Francisco,” says Goldstein. “There were cookbooks that were produced there, and it was a really vibrant community.”

Likewise, Slavic communities cropped up in Southern California and the Willamette Valley, which stretches across Oregon from Eugene in the south to Portland in the north. The Russian-speaking population of Los Angeles includes a strong corps of Soviet Jews who came to the city beginning circa 1970 as the Soviet Union imposed strict restrictions on their access to education and employment and denied their rights to cultural and religious practice at home. They developed their own Little Russia in Los Angeles’ Fairfax District, opening shops, pharmacies, bakeries and delis while upholding their religious traditions at local temples. Their bakeries and delis honored the traditions of both Slavic and Jewish cuisine. Today, tens of thousands of Russian-speaking Jews make their homes across Los Angeles, representing the second-largest population of Soviet Jews in the nation.

Farther north, Soviet Jews also migrated to the Portland area at the same time many of their compatriots settled in Los Angeles. Groups of Russian-speaking Jews also made Oregon home as much as a century earlier, fleeing pogroms under Tsar Alexander III, who ascended to the throne in 1881. Some founded small utopian enclaves in rural areas, like New Odessa, an agrarian socialist settlement named for the hometown of its earliest residents, established near present-day Glendale in 1883. But many more landed in Portland, where later groups of Soviet Jewish émigrés would join them.

Bonnie Morales (née Frumkin) was born in Chicago after her parents joined the exodus of Soviet Jews bound for the United States. They left Belarus and landed in Chicago in 1979 where Morales grew up and fell in love with food. As an adult, she moved to Portland, where she and her husband now own and operate Kachka, an award-winning Russian restaurant. The pair opened an adjoining deli and grocer called Lavka in 2019, where visitors can pick up loaves of bread, condiments, caviar, meats and cheeses. The shop also offers prepared dumplings, salads and other favorites like cabbage rolls, yeasted pancakes called blini, and a sweet-and-sour beetroot soup called borscht.

Like Fudym, Morales has childhood memories of visiting Russian grocers and delis for staple foods and cherished treats. “From as young as I can remember, going to a market similar to what we have now was a weekend errand every weekend,” she says. “It left such a big imprint, and it was something I referenced when we set out to open [Lavka].”

Oregon is also home to a significant group of Old Believers, descendants of medieval Russian Orthodox Christians who split from the Church after refusing to accept a series of 17th-century reforms. Groups of Old Believers began settling in the Willamette Valley some 60 years ago, their path to the Pacific Northwest a long and winding one. Subject to religious persecution after breaking from the Russian Orthodox Church, early communities of Old Believers scattered to the outskirts of the Russian Empire, building autonomous communities in the foothills of the Ural Mountains, Siberia and the Russian Far East. They were forced to flee again to preserve their religious traditions in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution, with the majority going to the Xinjiang or Manchuria regions of China.

“My ancestors had a long journey,” says Irene Konev, whose family fled Russia for Manchuria in the 1930s. When the Soviets invaded China in World War II, the family was displaced to Hong Kong. A few years later, large communities of Old Believers who had begun to build lives in China were resettled in Brazil, Argentina or Australia with support from international organizations like the Red Cross. Konev’s ancestors were among those resettled in Brazil, and she still has some cousins there. But her family and many others found the South American climate unfit for their self-sustaining lifestyle of farming, foraging, bee-keeping, hunting and fishing. “The community decided that the farming area was just not going to be able to sustain them,” Konev says.

Again, international organizations helped many, including Konev’s parents, relocate in the 1960s. This time they moved to Woodburn, Oregon, about 30 miles south of Portland in the Willamette Valley. The valley’s fertile soil held the promise of farms teeming with raspberries, gooseberries, strawberries and chokeberries, like those the Old Believers had tended in Russia and China. The lush underbrush and evergreen trees of the Cascade Mountains also cradled mushrooms, another pillar of Slavic cuisine. The Pacific Northwest felt a little more like home.

Today, more than 100,000 Russian-speaking immigrants and refugees from the former Soviet Union make their homes in Portland, and Oregon ranks second in the nation for Russian-speaking newcomers. Most of the recent migrants have been Evangelical Christians. Each new arrival adds another layer to the rich and entangled histories of Slavic migration to the West Coast and brings strength to its burgeoning Russian food scene, which has been simmering just beneath the surface for more than a century.

Markets and delis like Fudym’s New World Market in San Francisco and Morales’ Lavka in Portland offer Slavic migrants and their descendants a taste of old family recipes and a sense of pride. “It’s something the community here is proud of,” says Morales of her work at Kachka and Lavka. “I know a lot of people are really excited to be able to share—like they’ll have a co-worker who they can bring in, and be proud to share this food.”

Meanwhile, for newcomers to Russian cuisine, these grocers and delis offer opportunities to bring meat-filled dumplings, caviar-topped blini, and full-bodied broths into their own kitchen. If you’re among the unacquainted, there has never been a better time to welcome these centuries-old tastes and traditions onto your table. They’ve been carried a long way.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.