My grandmother wasn’t much of a cook. She was more of an eater and a talker, always ready to open up the next bottle of wine or offer a piece of life advice, which would usually teeter on the edge between helpful and ever so slightly cutting. Yet when I sit back to think of her, my mind always settles at the image of a bowl of steaming potato soup. It was the one thing she made me and my brother when we’d spend weekends at her house in the countryside. Usually, she was too busy walking the hills around her house, listening to Frank Sinatra, or reading biographies about the royals to mess around with any proper cooking. This soup, though, would always appear magically before us. Her voice would come piercing through the back door, beckoning us inside from an afternoon playing in the garden. We’d run inside to find two white china bowls filled with thick, creamy puree, with hunks of potato and leeks slick with butter. To this day, it’s the first thing I crave when it’s cold outside.

With this small but significant memory in mind, I arrive at Restaurant Maison Blanche, just off the Champs Elysee in Paris, for a dinner hosted by some of the greatest chefs on earth, using recipes inspired and passed down by their grandmothers. The dinner, entitled “La Cuisine de Grand-Mère,” is the passion project of entertainment industry veteran and food fanatic Steve Plotniki, who launched “Opinionated About Dining” back in 2007. Disgruntled with the rigidity of traditional dining guides and awards—and the chaotic echo chamber of online ratings—Plotniki began the initiative as a way of celebrating the world’s finest restaurants and chefs. Along with industry experts and selected global voters, OAD formed its first list of best restaurants, arranged by region. Now in its tenth year, OAD has established itself as a unique platform—with legendary parties attached to each ceremony.

Today, Plotniki greets us on the terrace at Maison Blanche, a bright, glassy restaurant stretched across several levels. Goodie bags are being arranged, white cloths are billowing onto tables, and the silverware is being polished in preparation for this evening when the room will fill with noted food journalists, OAD disciples, and families of the chefs. The air is charged with anticipation, and every so often I catch sight of one of tonight’s chefs shuffling into the kitchen to throw on their whites and get to work. We meet the cooks one by one, ushering them out onto the terrace where the Eiffel Tower looms over us. As the sky darkens, it starts to glitter, a beam of light jutting out across the city’s rooftops like a gold-dipped lighthouse.

The kitchen guest list includes Alain Passard, Rasmus Kofoed, Atsushi Tanaka, Mauro Colagreco and Quique Dacosta. Such a scene, with such an world-renowned arsenal of chefs, might easily edge toward exclusivity. It might even be intimidating. Yet, despite the glamour that clings to every surface of the room, a friendly, light-hearted air pervades. This comes down to the women who have inspired each dish on tonight’s menu. One by one, we discover the story behind each chef’s dish, from a tartar based on a Japanese fisherman’s dinner to the hearty, restorative suppers of the Swiss Alps. Every plate of food served at this long, luxurious dinner comes from a family memory, with recipes and techniques passed down through the generations. Although the winners of the OAD Best Restaurants were announced (Alain Passard’s L’Arpège came out on top), there’s scarcely any sense of competition. Which, for an international swarm of world-famous chefs standing shoulder-to-shoulder in the same kitchen, is pretty surprising.

Grandmothers, whether they appear briefly in our childhoods or remain with us for longer, can bring us many things: a break from the parents; a soft hand of comfort; a window into a past we’ll never know; a certain recipe. This evening, I watch world-famous, tremendously successful chefs soften as they describe their grandmothers. Their eyes turn glassy, smiles stretch across their faces. Some knew their grandmothers well, others only for a short while. But in these dishes, which we enjoy over the course of a five-hour evening as the sky above Paris turns inky blue, memories come deliciously to life.

Atsushi Tanaka

Restaurant A.T.; France

Born near Kobe on Osaka Bay in central Japan, Atsushi Tanaka has become an enigmatic figure of the international fine dining scene. Although the dishes at his critically-acclaimed Parisian restaurant A.T. are flecked with Japanese influences, they are a combination of Tanaka’s dynamic tastes, from the French fine dining he spent decades perfecting, to the molecular Spanish gastronomy that continues to inspire him. He is an amalgam of every kitchen experience, which includes time beside Pierre Gagnaire, to Belgium’s Pastorale, Oaxan in Sweden and Oud Sluis in The Netherlands.

His grandfather was a fisherman for over fifty years, and each day, he came home with a fresh catch for his wife to prepare for dinner. “I wouldn’t say my grandmother consciously influenced my cooking,” he tells me. “But I grew up watching the women in my family cooking from scratch every day.”

It is this appreciation for everyday flavors that inspires Tanaka’s dish tonight. He is making a horse mackerel tartar with asparagus—a play on Japanese sashimi using a “popular, cheap” variety of fish. His words, like his cooking, are spare, careful, and delivered with purpose. “I have a lot of good memories of my grandmother, and those times of her cooking for me. This is something we would eat a lot,” he tells me.

Tanaka’s grandmother passed away when he was fifteen, and while he may have gathered up culinary skills from across the globe, his cooking remains rooted to his home. “I never stop cooking in a classic way, even as I experiment,” he tells me. “It’s important to me to me to keep tradition alive in my cooking.”

Rasmus Kofoed

Geranium; Copenhagen

Rasmus Kofoed’s grandmother sits across from him at the table, beaming proudly as he recalls his childhood in rural north Denmark. The decorated chef, whose restaurant Geranium became the first three Michelin-starred restaurant in Copenhagen in 2016, moved to the countryside when he was ten. “I had a lot of energy as a child. I loved to run around the forest and climb trees,” he says. “Nature was important to me, it helped me learn about myself.”

He explains, “I’d open the door and be in the center of thick trees and plants and flowers. We’d go mushroom hunting, to pick rosehip to make tea, to use freshly ground elderflower or nettle shoots for soup. The use of flowers and seasonal herbs—to use nature—is what everyone does now. And they can’t stop talking about it. But I grew up watching my mother and grandmother doing that. That was just what they knew.”

Rasmus has become one of the most celebrated Nordic chefs of all time, and tonight, it is easy to see the influence he has on his peers. All eyes turn to his hands in the kitchen, which delicately construct a dish of cabbage stuffed with pork and horseradish juice, with marinated fresh peas and a scattering of silky flowers. “This is a spring version of a traditional recipe my grandmother always used to cook me,” he explains. “I’m adding more color, but the base is the same. These are all very traditional, humble ingredients.”

I ask his grandmother if she’s tasted the food at his restaurant. “It’s always very good,” she tells me, smiling. “I love it there. There are always big plates with very small things on them.” Her summer house was near Rasmus’ childhood home, and he recalls long, conversation-filled mealtimes at the center of his visits. “I think my grandmother influenced my cooking in an abstract way,” he says, meeting her eyes. “I remember when I was visiting her, there was a lot of joy around the table. My grandmother would sit for five hours with a lot of different dishes on special occasions. You would always get at least three servings. And always a dessert—traditional chocolate, caramel or vanilla puddings. But even though I was just a child and I found it hard to stay in one place, I could see they were all laughing, having great conversations, enjoying great food and wine. I saw the effect food could have.”

Mauro Colagreco

Mirazur; France

Bright-eyed, warm Mauro Colagreco greets us with a grin. The Argentine chef, who runs the kitchen of the two Michelin-starred waterfront brasserie Mirazur in Menton, France, is getting ready to cook the dish that has stayed warm in the memories of his childhood. It is a steaming cod with pepper sauce, olives, capers, tomatoes and chopped parsley. It is colorful, comforting and misleadingly simple; the kind of food that makes you want to hold the bowl with both hands. “It’s the flavor of my grandmother,” he smiles. He utters her name with pride: Amalia Blanco de Colagreco brought the recipe with her to Argentina when she emigrated there from the Basque region of Spain in 1913. She was just a child when she moved across the world, but Colagreco explains her recipes all came from those early years in Bilbao.

The chef grew up in La Plata, not far from central Buenos Aires. He lost his grandmother at age fifteen, but recalls the drop-by dinners they would have at her house in the countryside. “We’d pass by for holidays—Christmas, anniversaries, birthdays. It was always a party in that house,” he laughs. “She didn’t teach me to cook, exactly. But she translated the passion of cooking over to me, and taught me to do it with love. She was an extraordinary woman.” In fact, Amalia’s portrait hangs in the kitchen at Mirazur, watching over Colagreco and his team as they pour this very ethos into every plate.

Later on, when his rich, parsley-flecked dish reaches our table, it is impossible not to picture Amalia throwing together the ingredients, clinging proudly on to the flavors of her native land. “When I think of her, I think of love.” Colagreco says. “When she cooked, she did it from the heart. Her cooking always brought us together as a family. There was always, always something to eat in her house. I remember her cooking from the moment I woke up to the moment I went to bed. I choose to take her with me everywhere.”

Quique Dacosta

Quique Dacosta; Spain

Quique Dacosta is a self-taught leader of the Spanish avant-garde culinary set. His namesake restaurant straddles the coast of Denia in southeastern Spain and regularly tops the lists of the world’s best restaurants. Dacosta has amassed a following for his risk-taking, plinth-worthy dishes that celebrate the ingredients of the local region, all sourced within thirty kilometers from the kitchen. He joins us on the balcony with his grandmother, who exudes the kind of sun-drenched warmth befitting of the woman he calls his second mother. “My mother’s name is Mama Anna, and she is Mama Mari,” he says. They sit with their sides touching, his hand wrapped in hers. Every so often, he turns to her and grins, kissing her hand and tightening his grip. For all of his world-reaching accomplishments, it is easy to picture him as a boy through her eyes, standing in a shaft of maternal affection.

Dacosta was born in the Extremadura region of Spain, a vast and remote region of lakes, forests and scorched mountains. He grew up in a house with both his mother and grandmother in an area fuelled by goat and sheep farming. Tonight, he cooks a typical dish: a suckling lamb stew. The recipe, which is passed down from his grandmother (and “every other grandmother in the region”), calls for the whole animal, which is browned in a bed of oil with onion, garlic, hot paprika, tomatoes, and traditional Pitarra wine. The dish is then scattered with fried bread, crushed almonds, and another glug of red wine. Dacosta explains this dish exemplifies comfort food.

Dacosta left Extremadura when he was still young, moving off to other parts of Spain and getting jobs in restaurant kitchens “to pay the bills.” But his grandmother continued to influence him, less in the kitchen than in the world as a whole. “Certainly, my cooking is inspired by looking back at my childhood,” he tells me. “But Mama Mari’s influence on me was bigger than that. It doesn’t come down to her cooking; it’s about the human being that she is.”

Alain Passard

L’Arpège; France

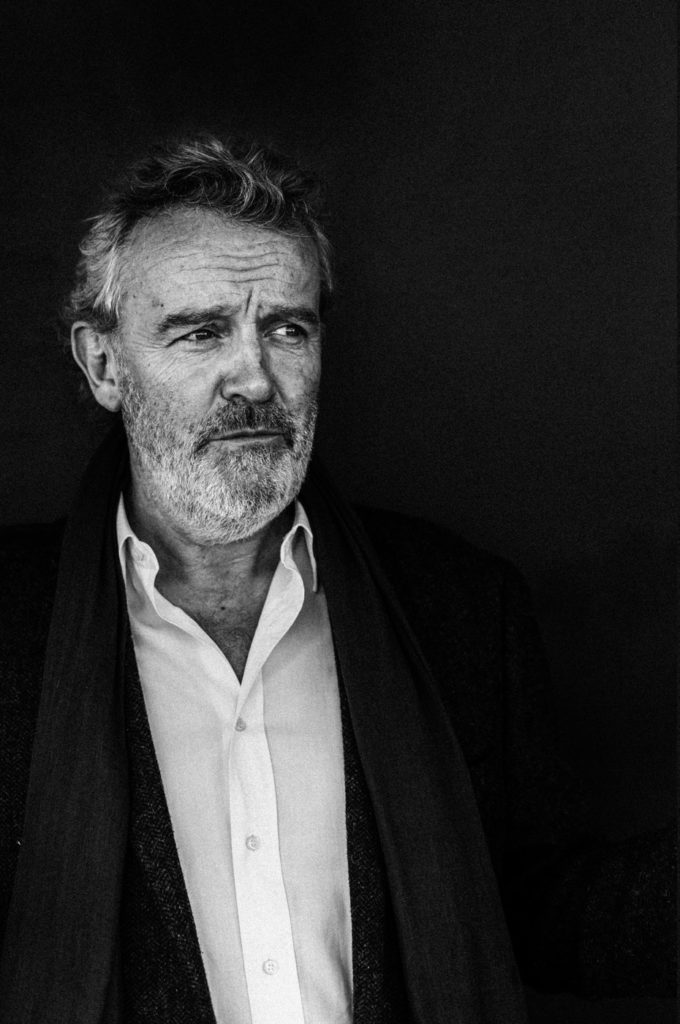

Alain Passard has the kind of encompassing, room-filling presence you’d expect from a man who runs one of the most celebrated restaurants on earth, the three Michelin-starred Art Deco veg-centric culinary palace L’Arpège. He strides up wearing a navy linen jacket, a pristine white shirt, and a silk cravat. His hair is thick and disheveled. He is charming and warm, but his eyes flicker around the room. He is never far from the next step. At L’Arpège, the produce for his meticulous, artful dishes comes from his very own “kitchen gardens,” which are tended to by twelve gardeners and watched over by a swarm of donkeys, cows and goats.

Tonight, his recipes pepper the expansive menu. There is a delicate “hot and cold egg served inside its speckled shell with sherry vinegar, spices and maple syrup.” There is also a warm, crumbly rhubarb tart he calls “Bouquet de Roses.” Like the man, the dishes have an air of theater about them.

His own grandmother lived in Brittany, and as he tells me about her, he leans in. “My grandmother is the source of all my cooking,” he says seriously. “She taught me how to smell, how to listen, how to feel the warmth of the season. Everything I do comes from her. All of my gestures in cooking come from her. She is a daily source of inspiration.” And this woman’s criticism was enough to throw him in the kitchen. “When she would say things like, ‘You’ve been a little heavy-handed,’ I would be devastated,” he remembers.

“I like to use old objects, wooden spoons and old knives that my grandmother used to use. It’s important for me to stay close to these objects––to stay close to her; to the warmth.” A sentiment that sounded, unsurprisingly, even more beautiful in French.

Andreas Caminada

Schauenstein; Switzerland

By the time he was thirty-three, Andreas Caminada had been awarded three Michelin stars. His leading restaurant Schauenstein can be found in a seventeenth-century castle high in the Swiss Alps—a storybook scene of tall grass, rolling hills, and grazing cattle. This Alpine backdrop is nothing new to the internationally-acclaimed chef, who grew up in Grisons, the easternmost canton of Switzerland. His village was perched 1,448 metres above sea level, with a population of just 355. He describes the food of this region as “tasty and heavy,” catering to a farming region with little money and an appetite for rich, weighty food that sticks to the ribs. He was too young when his grandmother passed away to remember nuances, but holds on tight to the culinary traditions of his home. He cooks up scrambled potatoes, dumplings with dried, crumbled meat, and buckwheat pasta with swiss chard and smooth apple puree. It smacks of the windy, wild Alpine edge of Switzerland.

And while the closest we’d been to physical exertion all day was skipping through the cobbled streets of Le Marais, it was easy to imagine coming home to this kind of food after a long, windswept day in the mountains. “Farmers need power food. So that’s what we have tonight,” he explains. “I wanted to tell the story of my family in the Alps. Every grandmother has her own version of these dishes. This is not a show-stopping dinner, it’s about celebrating traditions. This is the food that shaped us.”

David Toutain

Restaurant David Toutain; France

Although he has garnered a reputation for boundary-breaking vegetable dishes at his Michelin-starred Parisian restaurant, David Toutain is never far from the memory of summers spent on his grandparents’ cattle farm in Normandy. “I used to watch my grandparents slaughter the animals, and my grandmother used to serve everything—the giblets, the brains, the sweetbreads. Nothing would go to waste,” he remembers. “Everything that wasn’t used would go into a terrine.”

Tonight, he is paying tribute to his grandmother’s resourcefulness with a sweetbread terrine, cooking up the giblets and using up the remaining parts to make the soft, unctuous slices, served alongside a chicken mousse and mushrooms. “I remember eating this at the dinner table; it was always so comforting to me,” he says. “It wasn’t perfect, so I’ve adapted it slightly. But only slightly. I think my grandmother would like it this way.”

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.