![]() The Plants Issue

The Plants Issue

Read the Editor’s Note

Like salt, pepper, honey and lemons, herbs are always closeby in the kitchen. They stand in wait, ready to be scrunched up, torn or scattered finely across a dish. They can be sturdy and dominant. They can be whisperingly soft. They come and go with the seasons, and like delicate flowers, they shrink and wilt fast—their short lifespans make them precious.

Asking six of London’s most accomplished chefs to choose their favorite herb was always going to be tricky; when your passion is ingredients, selecting just one is a struggle. Press them on the topic, though, and there is always one that jumps to the surface like a rogue grain in a sieve of flour. Choosing a favorite may be challenging, but certain herbs conjure stories of sight and scent. They evoke memories of dishes that shaped a life.

Olia Hercules

Food Writer

Favorite Herb: Tarragon

When I visit Hercules one overcast afternoon, she has just returned to London from a month travelling around the Caucasus shooting her second book. Her trip ended in Ukraine, where she was born.

Hercules’ childhood was spent among the cherry and walnut trees, watermelons and gooseberries that grew in abundance in the land that surrounded her hometown of Kakhovka. There, she learned to use food seasonally, pickling and preserving produce for the winter months and celebrating every fallen fruit and plump vegetable in the summer. She has been in the U.K. for over a decade now, and over the last couple of years, she has made London sit up and observe the wonders of Eastern European food. Her first book, Mamushka (named after the Ukrainian mother, Armenian aunt and Siberian grandmother), is a love note to the decadent, intense flavors of Ukraine “and beyond.”

“All over Caucasus, they really use tarragon,” she explains. “It’s not like in French cooking, where they just sprinkle tiny little pieces in like this.” She mimics a tight-fisted cook. “They properly chuck it in.”

To Hercules, tarragon is the herb that defines Caucasian cooking. She tells me about tarragon tea, and pie with chopped boiled eggs and tarragon in Georgia. She talks about a Ukrainian dish that combines the herb with beetroot and plums. Her Armenian auntie used the herb religiously, inspiring the tarragon flatbread she makes today. Standing at her deep stone sink, which is overlooked by tarnished copper pans and family photographs, she runs the water over the leaves. “At the markets in Georgia there are Azerbaijani women selling mountains of herbs,” she tells me. “Georgians call them baji, which means ‘sister.’ They have their hair tied up in colourful scarves, and the tarragon is bundled up with these little wooden pegs.”

Hercules picks up a bowl from the table and breaks off the tops of a few leaves. She offers them and we stand in her kitchen, the door propped open to the garden, considering the flavor. “It kind of numbs your mouth. Which I really like,” she laughs. And it’s true—the sensation of fresh tarragon begins soft on the tongue and lingers for minutes afterwards, almost medicinal in its strength.

In all of Hercules’ cooking, from her coriander mutton and beetroot broth to her cardamom pastries and fennel, rhubarb and radish pickle, the flavors are as punchy and strong as her own spirit. “There’s nothing delicate about the flavor of tarragon. But that’s what I like in all cooking,” she says. “For me, flavor has to hit you in the face. Lovingly.”

Tom Hunt

Chef of Poco

Favorite Herb: Oregano

I have come to visit Tom Hunt in Southeast London, where he lives in a housing cooperative built in the 1970s; a line of shared terrace houses with wild flowers and thistly branches twist over the doorways. His kitchen has a hefty concrete table in the middle, a guitar in the corner, and ceiling-high cupboards hand-built from wood. This kind of setup suits Hunt, the “eco-chef” and food waste activist whose root-to-tip philosophy commands the kitchen of Poco, his East London restaurant. He believes in using ingredients when they are ripe and ready, taking advantage of every inch. Inspiration for Hunt’s dishes span the globe, from the heat of the Middle East to the pared-back elements of Nordic cooking, or Spanish tapas, all showcasing local produce.

Hunt heads out into the shared garden, where velvety nests of sage sit beside milky pink raspberries. The garden is wild and brimming with vegetables. “My ‘favorite’ is what is best at that moment, in whichever season we’re in. It is so hard to pick one herb that I love more,” he says. The inquiry forced Hunt to examine his current garden. “I came out to see what was in abundance, and was drawn to oregano,” he says, holding a bunch of the soft leaves in his hand, long and bright, with little purple flowers like crowns at their tips. He twists another few stalks up from the soil and holds them to his nose. “I get a lot from the smell of oregano. It’s perfumed and sweet. It’s got that lovely grassy smell,” he says as he tears off some leaves and hands them to me. They are cool and moist with oils—imperfect, organic specimens at the prime of their life.

“It makes me think of summer, and of the Mediterranean. It makes me think of food that I like to eat; fresh, light summery dishes steeped in olive oil,” he smiles, relishing the thought. As he inhales the leaves, another pops into his head. “And it reminds me of cooking with Francis Mallmann.” Not long ago, Hunt attended the Ballymaloe Literary Festival in Ireland; the dream was to meet the iconic Patagonian chef Francis Mallmann. The reality was even more magical. “I ended up cooking with and assisting him for 12 hours,” Hunt explains.

Beside his culinary hero, he scored huge beefsteak tomatoes and filled in the cracks with slices of garlic and fresh oregano leaves. They were cooked on a giant sheet of steel over a fire until their skins had charred and the oregano and garlic melted in. “One of my main purposes of cooking is to bring people closer to the origin of their food. Francis Mallmann does that through his visceral and grand cooking techniques. Fire is so dramatic and spiritual. It’s a portal back to our roots in nature,” he says. “This smell transports me back there.”

Meera Sodha

Food Writer

Favorite Herb: Curry Leaves

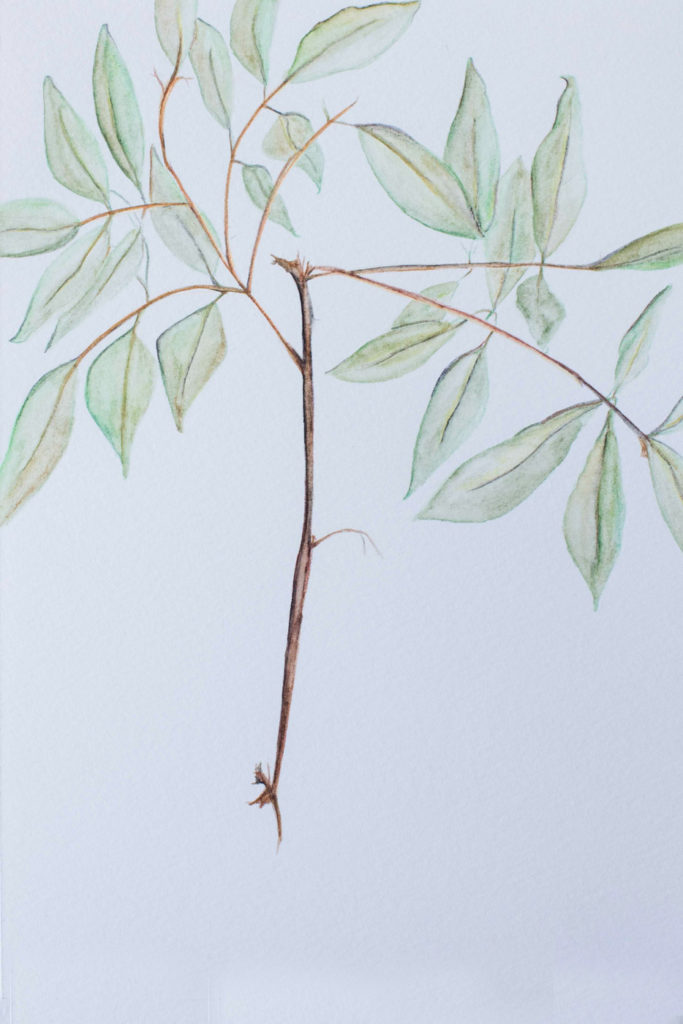

There is a line of plants on the back wall of cookbook author Meera Sodha’s kitchen. They stand at attention, each arching over the other in a bid for attention. The tallest is a pot of curry leaves. The trunk of the plant is thin, climbing toward a crown of greenery. These are the leaves Sodha reaches for first when she begins cooking; they are central to the light, zesty Indian food she has brought to London in books like Made in India and Fresh India.

Sodha learned everything she knows from her Gujarati mother, who moved to England in the 1970s following the expulsion of Asians from Uganda by the vicious dictator Idi Amin. She grew up watching the women of her family bring the food of their country to rural England, cooking spicy samosas and pigeon curries for curious neighbors.

As a self-proclaimed rebellious teenager, she steered clear of the kitchen. It wasn’t until a trip to a “horrible” Indian restaurant on Brick Lane that a need to recreate her native food was sparked in Sodha. Her friends asked her what they should choose from the menu, one stocked with lurid orange jalfrezis and textureless chicken kormas. “It just wasn’t the food I’d grown up eating,” she says. “I was suddenly overcome with the desire to show my friends true Indian food. The only problem was, I couldn’t create a meal.”

Sodha began racing back and forth from London to her parents’ small village in Lincolnshire, observing her mother in the kitchen and gathering up a trove of family recipes. “That early time of not cooking helped me,” she explains. “I think if you reject something, then come back to it later on in life, you see it through different eyes.”

The scent of curry leaves and onions cooking in oil is unmistakable walking into Sodha’s East London house. “That smoky, citrusy smell is South India to me,” she says, tearing off a little branch and crunching them in her hand. “It reminds me of Kerala and Cochin, of the inside of people’s homes. The leaves hit the oil and you can smell them straight away. They’re beautiful.”

She stirs the medley into fluffy white rice flecked with tamarind and caramelized onion. With it, she serves coconut prawns, the base of which—like so many great Indian dishes—is a handful of curry leaves. They simmer and spit at the base of the pan, propping up the flavors like a loving hand, leading you through a crowd. “Curry leaves are a very generous herb,” she comments, pouring the dal into little tin bowls. “Coriander wilts the moment you add any heat. Parsley tends to disappear, too. There are a lot of fickle herbs. But curry leaves are robust; they never stop giving. They stand their ground.”

Florence Knight

Former Chef of Polpetto

Favorite Herb: Bay Leaves

Chef Florence Knight thinks bay leaves have been forgotten. “I feel like they’ve been left behind,” she says, standing at the small wooden island in her kitchen. “They remind me of my grandmother’s cooking; she used to cook very traditional English food.” She recalls meals like pearl barley, lamb slow cooked in a pot, and thick, hearty celery soups—all made with bay leaves. “Bay is very romantic and nostalgic for me.”

My afternoon with her feels a lot like visiting an old friend’s country cottage. There are black and white checkered floor tiles, a large communal table, and lovingly weathered surfaces. It is both the kitchen of a great chef and a growing young family. A wooden crate of bay sits on the table, nestled among fresh vegetables.

Knight is the former head chef of celebrated Venetian small plate restaurant, Polpetto. She made a name for herself cooking rich, comforting food—stewed pulses, crumbly meatball pizzetta, chickpea and anchovy crostini—the kind of food you’d like to come back to after a day of delayed trains and cold rain. Now, Knight is in the process of opening a restaurant of her own, and to Knight, there is no herb that combines England and Italy more than bay leaves. “[The leaves] came from Italy to England, via the Romans,” she remarks. I’m reminded of one particular dish of Knight’s: “drowned tomatoes” drenched in olive oil and garlic, and cooked with a couple of bay leaves.

“They have a flavor I relate to mature, slow foods. It’s that mellow, comforting, medicinal element I love,” she continues. “With other, more aggressive herbs, you’re looking for a way to balance the flavor. But with bay, you have to encourage it. You have to coax it out of its shell a bit.”

If bay were a person, it would be a quiet, watchful character who breaks into a flurry of wit and charm only when the time is right. “I like the neglected element of bay. You may not recognize it when you eat it, yet it is distinctive and familiar at the same time. We really take it for granted,” she says, pouring me another cup of tea. “And it can be wonderfully indulgent. If you combine it with caramel or put it in hot chocolate, it can suddenly become this intense, comforting flavor.”

Bay leaves have no scent until torn apart, and can transform the most unlikely dishes, which is why they’re never far from Knight in the kitchen. “Bay is like a solid friend you can rely on all the time—who’s not a show off.”

Ramael Scully

Chef of Nopi

Favorite Herb: Marjoram

There are few people who talk about food like Ramael Scully. He reminds me of a musician friend, who adores everything from wind chimes to screamer rock, and talks about the nuances of every sound with equal passion. Scully—most commonly known only by his surname—is the same. The head chef of Yotam Ottolenghi’s “grown up” restaurant, NOPI, and co-author of its follow-up cookbook, has an encyclopaedic knowledge of ingredients and cooking techniques. His mingling Indian, Malaysian, Irish and Chinese heritage has massively influenced his cooking, cross-pollinating with Ottolenghi’s Middle Eastern flavors to create the NOPI menu.

Scully is never more than a few feet from a kitchen. The first time I met him was in Ottolenghi’s kitchen, where he was cooking a pistachio and pine nut-crusted halibut. I next saw him in action at NOPI, whipping up black rice pudding with coconut milk and shakshuka at breakfast time. Today I am in his home kitchen in North London, and now it is hard to imagine him in any other setting. He gravitates toward the pots and pans, the knives and flames, the endless flavor combinations inspired by feasts with his Malaysian aunties and his travels through Asia.

Around his kitchen are hints of tireless culinary experiments. In one corner is a jar of preserved lemons flecked with herbs and spices. In another, he is experimenting with a few types of kombucha. He has been dehydrating whole zucchini and burning various fruits and vegetables, like the corn skins that he now lifts out of the oven in long, crackling strips. “The greatest chefs don’t find themselves until later on in life,” he remarks as we discuss his indefatigable recipe writing, before moving onto his herbal pick.

“Marjoram is like the herb that time forgot!” He tells me this curious herb is hard to come across. Just a few hours ago, he visited the famous Borough Market vegetable aisle and asked for a bunch of it. The trader had never heard of it. “People are afraid of marjoram because it is really hard to find. It’s not readily available for people to experiment with, so they are less likely to pick it up if they do find it. I read a lot of cookbooks, and I rarely come across it.”

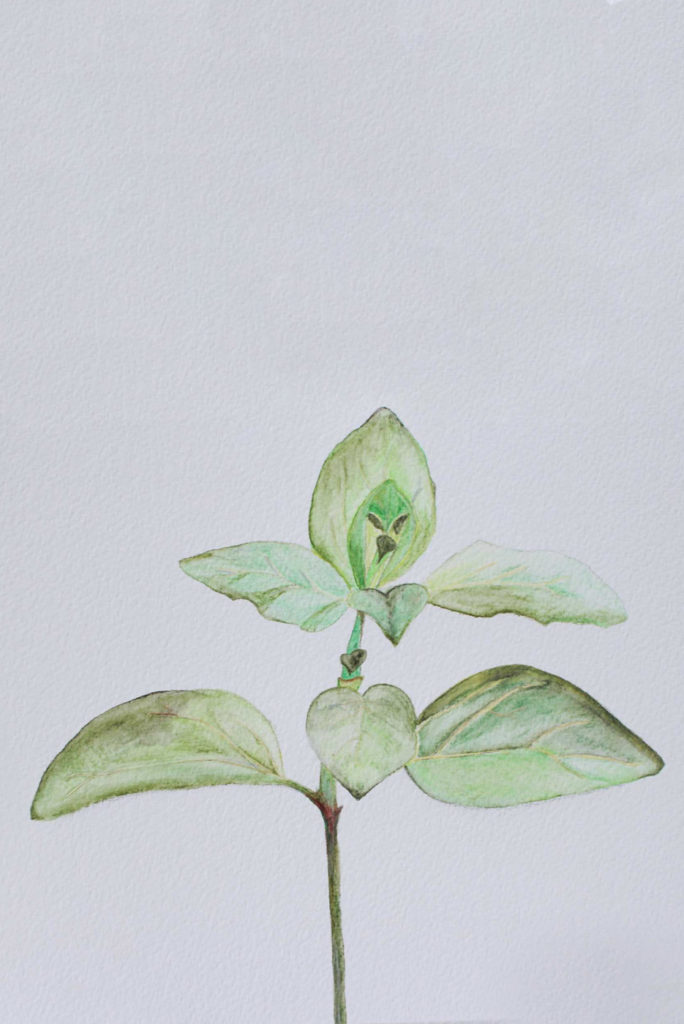

Marjoram is a relative of oregano, with wide, glossy leaves, most often found in Middle Eastern or Mediterranean recipes. “To me, oregano is the male version, and marjoram is the female version. It’s lighter and more delicate,” Scully says.

He gets to work on lunch—corn kernels sautéed with marjoram, spring onions and shiitake mushrooms served with sheep’s yogurt, grated cucumbers, and burnt corn husks. The result is subtle, carried by the lemony, piney freshness of the marjoram.

“I first came across [marjoram] in my twenties when I worked with an Italian chef in Sydney. He taught me how to make salsa rosa, which is marjoram pounded with paprika and coriander. It always reminds me of starting out,” Scully remembers, and notes that when he arrived in London, he hadn’t seen the herb in years. Today, he has found his source. “I started working with a Cornish farmer who grows little baby marjoram. They’re beautiful. They bring so much life to simple dishes. I want to give it the attention it deserves.”

Selin Kiazim

Chef of Oklava

Favorite Herb: Coriander

Selin Kiazim is getting married soon. The color for the wedding will be teal, the same shade as the stone oven in her Shoreditch restaurant, Oklava. It’s her first permanent space, perching on the corner of a quiet street of sand-colored brick buildings, a few steps from the bustling heart of East London. Kiazim started out hosting pop-ups around London, serving dishes based on her Turkish Cypriot heritage. It is the kind of food that silences a tableful of friends, drenching the moment with enough color and flavor that words become secondary.

Among dishes like lamb with sour cherries, monkfish with blood oranges, bread with medjool date butter and za’atar crumbed chicken, lovers of Oklava rejoice in the restaurant’s famous pides. These soft flatbreads are stretched out like a boat’s oar, bursting with octopus and honey with ricotta and green olives, or potato with leek, mozzarella and fresh summer truffle. The restaurant, Kiazim tells me, is named after the rolling pins used to flatten the dough.

Every dish that comes out of Oklava’s open kitchen is embellished with spices and seeds, wedges of citrus fruits, and twisted piles of fresh herbs. Coriander is always a feature, glistening with lemon juice or folded in to fresh salads. “I suppose coriander is the herb I use most. It’s so incredibly versatile,” Kiazim says, pulling up a chair as lunch service winds down. “My favorite part is the stalk. There’s so much flavor in there.”

Kiazim recalls a salad her mother and grandmother used to make when she was growing up—a shredded cabbage dish with orange segments, red onion, and whole leaves of coriander dressed with lemon juice and olive oil. “I remember loving the way the coriander cut through the rest of the flavors. It’s so dominant and over-the-top fragrant,” she says. Kiazim is fearless with the herb, using it not as a garnish, but as the main body of many dishes. “I love it because so many people dislike it,” she laughs, shrugging on her chef whites. “I will never understand that. Maybe I can help change their minds.”

Illustrations by Meg Abbott & Issy Croker

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.