It is a day made for postcards, travel brochures and for pulling to the side of the road for a photo; it is the kind of day where you simply can’t ignore the natural splendor of the Napa Valley.

Blessed rainfall has soaked the previously drought-stricken vineyards to the point of flooding in some areas. In these reflective pools the sunlight shines clearly, illuminating the effervescent yellow of the mustard flowers growing between the rows of vines. Against a backdrop of lush, emerald-colored hills freckled with wildflowers, the almost-black, gnarled and naked vines are the only indication that winter is not quite over.

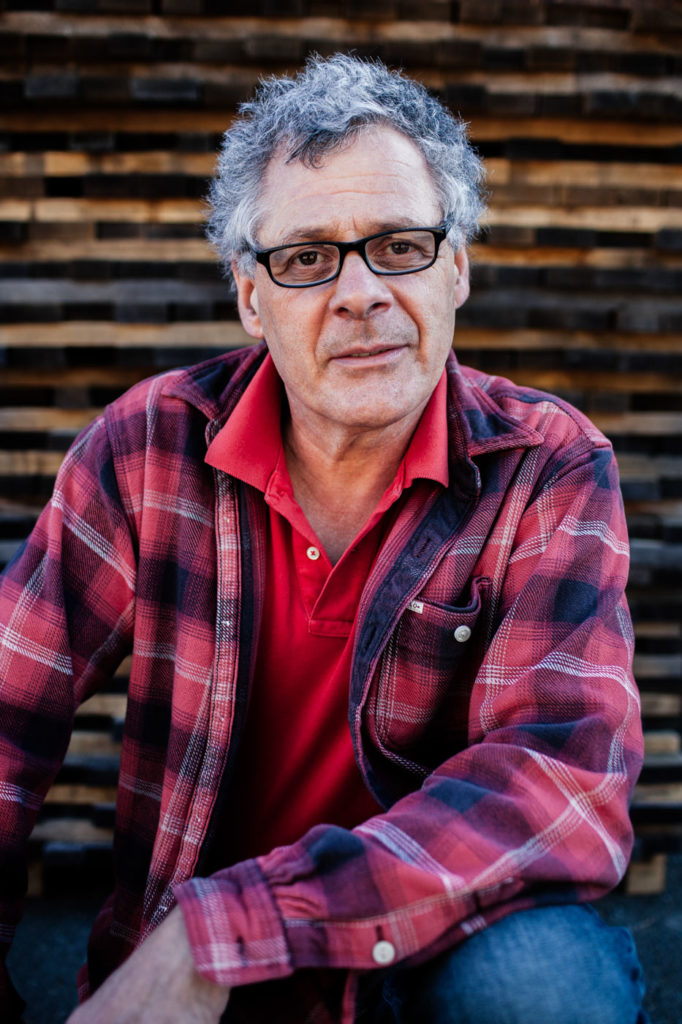

But, I am not here to see the vineyards or taste at the wineries; I have come to Calistoga to learn about cooperage––the art of barrel making––from Master Cooper, Alain Poisson, at Nadalié USA.

Much attention is given to vintners and sommeliers, to mixologists and microbrewers, but it’s not often one hears about coopers. Their craft has somehow gone unnoticed, but during the transition from the vineyard to the bottle, it is the artful work of the cooper that influences the wine. In an age of sterile steel tanks, oak barrels remain beacons of tasteful tradition in the production of alcohol.

Born in Burgundy, one of the most famous wine regions in France, Poisson was raised around the best of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, yet he was the first of his family to pursue a career in the wine industry. Of his interest in coopering, Poisson shrugs: “In Burgundy, if you don’t know what to do, you make barrels.” In the language of coopers, the word Burgundy is, itself, known as a common descriptor that characterizes the size of a barrel.

Many artisans romanticize their craft, but though Poisson may love and admire the art of barrel making, his emotions are tempered by a timeworn and hard-earned realism. Like any vintner or farmer knows, the production of high-quality goods at the mercy of nature and ever-changing trends is not easily done.

“There are no two barrels that are the same. We do not want that,” Possion tells me. “A tree is cut down, it is gone. You wait two hundred years for another one, but it isn’t the same. It depends on the terroir and the grapes, which change all the time. There’s no formula, but the winemaker tries. We must adapt all the time.” In his words, I find a lesson people are relearning across the artisanal food and drink movement: Beauty is not perfect, symmetrical or replicable; the beauty of art lies in the nuances that make it unique.

During his late adolescence, Poisson spent three years as an apprentice working under different Master Coopers in France. “When you begin coopering, your hands bleed. It’s very hard work to make a barrel,” he says. Despite the exhaustion of his first years, Poisson speaks fondly of this time in his life. “I was goofy and free,” he laughs.

Poisson dreamed of traveling the world. In his early twenties, he contacted Victor Nadalié, a fellow Frenchman, whose family cooperage had recently opened a new location in the Napa Valley. In 1980, Tonnellerie Française became the first cooperage to make American oak barrels in the United States using traditional French cooperage methods (the name was later changed to Nadalié USA.) In 1984, Poisson packed his things and moved to the Napa Valley to begin work as resident Master Cooper. Today, Poisson works with Nadalié’s son, Jean-Jacques, and grandson, Vincent, to produce vessels for some of the world’s best wines.

When Poisson first arrived, Napa Valley was experiencing a boom in the wine industry, thanks to The Paris Wine Tasting of 1976. At this historic occasion, French judges conducted a blind tasting and––much to their chagrin––unknowingly declared Californian wines the winners in two important competitions.

It was fortuitous timing for Poisson, but his interest was in the barrels, not the wine. “When I first started here, I didn’t know anything about wine,” said Poisson. “I knew wine because I was drinking wine like every French person. I wasn’t drinking wine out of barrels. I couldn’t afford it! I had to learn to drink wine that comes out of barrels. Now I can taste the difference between American oak and French oak.”

Developing a taste for distinct species of oak seems like an impressive talent, but Poisson is modest; his comments on wine border on reverence. Unlike the sometimes haughty attitude of sommeliers and the eccentricities of winemakers, Poisson gives the impression that he doesn’t take himself too seriously.

Even before entering the Nadalié cooperage, its architectural design hints at a sense of playfulness mixed with pride. The entrance is shaped to mimic a barrel; a wide arch lined with wooden staves. A silver bike leans against the sandy-hued stone block façade. Upon entering, there’s a distinctly woody aroma, warm and inviting.

Sitting in Poisson’s office, where he has worked for over three decades, it’s apparent that the charm of the cooperage has not worn off. “I like everything here. You come, you open the door, you smell the toasting––it smells so good,” he says enthusiastically. “I came here on my bike this morning and I heard the bang-bang-bang of guys banging on the barrels. I remember that from when I was young.” Though Poisson works outside of the production room of the cooperage now as Nadalié’s Vice President and General Manager, it isn’t hard to imagine him, even in middle age, banging away on the barrels with vigor himself.

Poisson has lived in California for most of his life now, but an endearing French accent lingers when he speaks, and the wine industry similarly retains its French heritage in many ways. When Poisson receives a call, he carries out the conversation in French, which is the primary language for much of the core team at Nadalié.

Cooperage is a craft of precision, but the materials––the wood that forms the barrels and the wine that fills them––are natural, and nature can’t be depended upon. Poisson had a deep understanding of different species of wood, their nuances and the competitive market to acquire high quality wood. From him, I learn more about trees in an hour than I have in my life––that American oak imparts a more aggressive flavor to the wine, while French oak is more subtle, and that in the U.S., we tend to cut down trees that are around 75 years old, while French coopers create their barrels from trees that have grown for roughly two hundred years. It’s all fascinating, but perhaps nothing more so than the process of aging the wood.

Like wine, the French tradition insists that wood becomes better with time. Poisson explains that after a tree is felled and cut into smaller pieces, the wood is stored outside for two to three years to age. There, the natural interaction with its environment eliminates any negative flavors in the wood. Without the benefit of aging in this way, the flavor would be green and bitter due to the tannins lingering in the wood.

Poisson tells me when wine is aged in oak barrels, “There is an exchange between wood and wine. It is because of the barrel that the wine is better.” He makes a short, dramatic gasp and leans in conspiratorially. “I don’t know if you can say that,” he laughs.

In the end, it is up to the winemaker to make decisions about the kind of barrel he or she believes will suit the wine they hope to produce. There are an infinite number of choices a cooper and winemaker must collaborate on. Poisson jokes, “I’ve met some really strange people. They all have a special formula in their head.”

Kevin André, a sales representative at Nadalié, explains the process during a tour of the coopering space. André is, coincidentally, also from the Burgundy region of France but also found a home in the Napa Valley; he explains, “I was tired of France. I like the spirit here.”

We start at the beginning, where a machine cuts the aged wood into staves. Nadalié uses machinery only to facilitate parts of the barrel making process that require especially hard, repetitive labor. Human expertise is still necessary for the artistic finesse that defines the craft. André points out that the machine cannot detect imperfections, so one of the coopers must individually examine each stave for wood that is splintered or knotted. Flawed pieces are used later as fuel for a fire in a part of the toasting process.

Nowadays, most coopers are only familiar with one task of the many involved in the coopering process. Poisson, in his training to be a Master Cooper, learned every detail. There are only a handful of Master Coopers left in the world.

The staves that pass inspection are then arranged by another cooper, who must find and piece together staves of different sizes to form one complete barrel. These pieces are held together on one end by a metal hoop to form the shape of a skirt, cinched at the waist and flaring toward the bottom. A second hoop will be hammered on later, forming the signature shape. There is no glue to hold together the wood––instead, it all relies on the cooper choosing perfect staves that will fit neatly together like a puzzle.

As we walk past a collection of finished barrels, I notice one has a special note. André removes the plastic wrapping, revealing several lines burned into the wood reading: “Nadalié USA, 12th Ping Pong Tournament, 2015. 1st Place.” André explains that Nadalié hosts an annual Ping-Pong tournament. As per tradition, the winner is given a barrel. It’s one of several quirks I discover that makes Nadalié feel more like a family than a business.

Next, André leads me to the room where barrels are toasted. Here, those imperfect pieces of wood have a new role. Because the room gets extremely warm, the coopers only toast the barrels early in the morning. Nadalié uses a traditional oak fire rather than gas-powered flames, to toast the interior of the barrels. Each half-formed barred is set over a small, controlled fire and a stream of water is sprayed on the surface of the wood. The steam makes the wood more pliable, so that it can be bent into the shape of the barrel, while the smoky heat imparts flavor. I imagine the effect is similar to Southern barbeque––a piece of meat roasting over a wood, and I think about how those earthy flavors could enhance a glass of wine.

A cooper can apply a light, medium or heavy toast to the barrel––or a level of toast elsewhere along the spectrum, depending on the winemaker. For fruity flavors and a subtle hint of oak, a cooper will keep the barrel over the fire for about thirty minutes (a light toast). For notes of chocolate, spice and coffee, the barrel can be toasted for roughly an hour (a heavy toast).

There is no machine to test the temperature of the fire or to time how long the barrels are toasted. This step of the process requires the presence of an experienced cooper to carefully assess the treatment of the barrel. It’s a skill that engages almost all the senses; the cooper watches the color of the wood change, touches it to test texture, and can detect when it’s reached the desired toast by an acute sense of smell.

I can smell a slight difference in the woody aroma of each part of the cooperage, but my distinctions are sentimental, not scientific. The scents call to mind campfires and freshly struck matches. I try to think of every instance of burning wood in my life and find that the occasions are few, but always special, and inspire a deep feeling of nostalgia.

As we reach the end of the tour, André runs his hand along the inside of a barrel, then leans over, pokes his head deep inside and inhales audibly. “It’s still warm from toasting,” he observes. I follow his lead and find myself immersed in the barrel, enjoying its comforting perfume and pressing my fingertips against the warm surface. When I examine the barrel from the outside, I notice faint wisps of smoke emerging from the bunghole, the round opening from which the wine will be poured.

There are approximately 4,000 wineries in the Napa Valley and only about a half dozen cooperages. Poisson observes, “Businesses that make a lot of wine don’t think barrels are worth it.” While certain spirits, like bourbon, are legally obliged to be aged in oak barrels, there are no regulations that require wine to come into contact with wood. Poisson estimates that less than five percent of the wine produced globally is aged in barrels. Most of the wine we drink is kept in steel tanks, which are cheaper and easier to maintain, but lack the romantic aesthetic of wooden barrels and the ability to add complexity of flavor to the wine.

It is the work of artisans, such as Poisson, to create a moment of pause in appreciation for something as seemingly simple as a sip of wine or the smell of an oak fire.

Like the best of winemaking, cooperage is a science and an art, but it’s also something that can’t be explained. As our conversation comes to an end, Poisson makes a confession: “There is no formula to make a barrel––and I hope we never find one! If they figure out how to do it with just a button, our work is gone, the magic is gone. We are magicians,” he says. I believe him.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.