Our oceans cover over 70 percent of the planet. They regulate our climate, they serve as a source of livelihood for millions––and of course, they also provide us with food. Our appetite for that food has grown exponentially in just the last few decades. The staggering increase has led to overfishing––largely unregulated fishing––and trawling, a fishing method that involves a net being pulled through the water, capturing large amounts of bycatch. On a global scale, approximately 39 percent of all stocks are being overfished, with only 48 percent measuring at a healthy abundance level, according to the Status of the World Fisheries for Tuna report released by the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation in February 2016.

The result has been a stark decrease in many main species. Oceana, an international ocean preservation and advocacy organization, estimates that more than 90 percent of the ocean’s top predators, such as sharks, swordfish, marlin and bluefin tuna, have been eradicated. There aren’t definitive numbers to accurately illustrate the impact our increase in seafood consumption, partly due to the fact that we lack a unified governing body to provide oversight and accountability on this issue. Some countries regulate their fishing practices, via efforts such as the European Union’s Common Fisheries Policy, but many others do not, so it is difficult to compile data that can provide an accurate picture of the effect of these practices.

According to National Geographic’s Pristine Seas project, a research endeavor led by Marine Ecologist, Dr. Enric Sala, this decline began in 1989. At that point, 90 million metric tons of seafood had already been caught, but large-scale industrial fishing continued. This resulted in the stark reduction of large ocean fish to 10 percent of the pre-industrial population. There has either been a stall in growth or a further decline in the species in our oceans.

Baja California, Mexico’s narrow peninsula, is home to a large array of diverse marine life. The eastern portion of Baja is met with the Gulf of Mexico, and the western portion with the Pacific Ocean. The peninsula can be divided into two main regions––the northern and the southern peninsula. Each region attracts numerous sport fishers and companies of varying sizes. Much like other parts of the world, Baja California’s waters have experienced a strain, and there is a growing movement to prevent further damage.

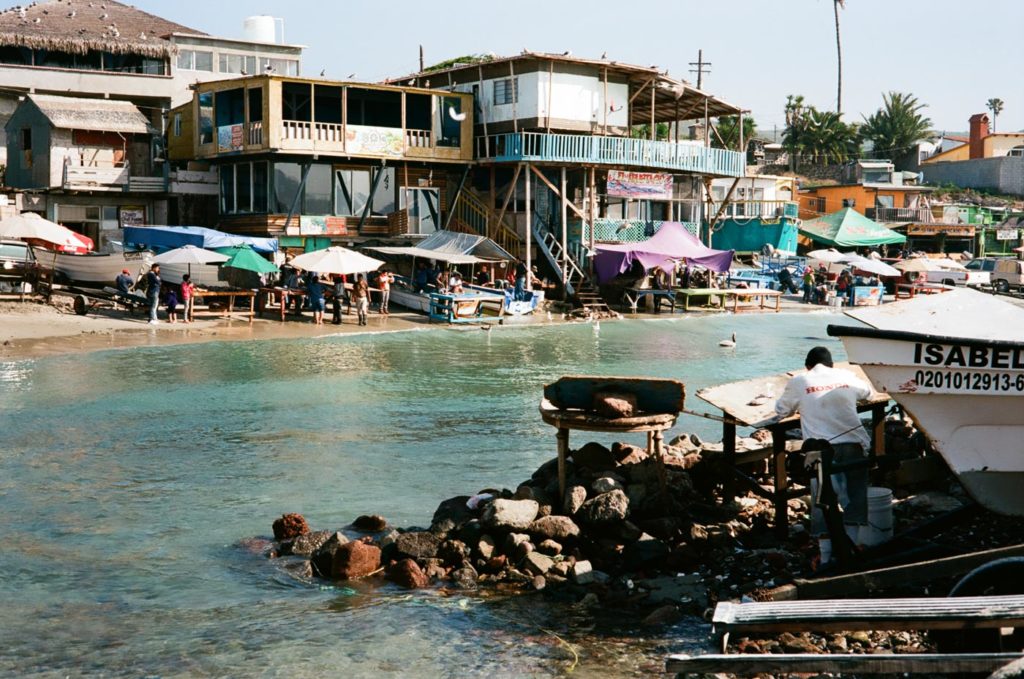

Recently, I traveled to Popotla in Baja California, just 45 minutes south of San Diego, to visit with a group of fishermen that have been living to support this dogma, helping to preserve the area’s seafood. This small fishing town lies between Rosarito and Ensenada, and often is overlooked by visitors––but I found Popotla to offer some of the freshest and most traditional Baja cuisine in comparison to many typical tourist stops.

I experienced how the locals catch, prepare and consume their food thanks to Think Blu founders and Popotla residents, Patty Villarreal, and her husband, Marco Bejarano, who invited me to spend the day with them. Over deep fried spider crab in a red pepper sauce and fresh clams with pico de gallo, the couple shared with me their story.

Bejarano had been a mechanical engineer for over 25 years, and Villareal a school principal for 12 years, but despite not having professional experience in the fishing industry, they felt compelled to find a way to impact the local fishing industry they admired. Bejarano had been sport fishing for many years; he had a love for the ocean, for its marine life––which Villareal shared. They instilled this sense of respect for nature in their children; weekly fishing trips were a family tradition.

The family wanted to start an organization that addressed environmental issues, created sensibility towards local products, and altered the societal perspective towards the fishing industry and local fishermen through education. They also hoped to promote the diverse species found in the region, while at the same time to discouraging overfishing.

Bejarano and Villareal were confident in knowledge they had obtained from local fisherman and from living in the region. Three years later, Think Blu has become one of the most sought out suppliers of seafood to restaurants in the region and is helping educate culinary students by providing them with firsthand experiences.

How did Think Blu begin?

Villarreal: It started back in 2013 after we decided to submerse ourselves in the community that we love. We came to Popotla to start selling locally caught fish and give a voice to the fishermen. We started off selling Bluefin tuna and it grew from there.

On what market does your organization focus?

Villarreal: What we sell here is for local clients, for local restaurants. Some people get lazy, they want to go to Costco––which is fine, but it’s not fresh.

What are the fishing practices and regulations here in Popotla?

Bejarano: Most of the fishermen use single pole and line fishing to reduce the amount of bycatch. There are local regulations on what can be caught and when. For example, we have two types of sea urchin––red and purple. The red ones are the bigger ones that get shipped to Japan and they cannot be caught from February through the beginning of July. This gives the species a chance to reproduce. The smaller purple ones can be fished all year long, they don’t have a season. The Mexican Navy typically are the ones going up and down the coast checking the boats for permits, size and species of the boats catch.

What are some of the limitations that impact local fishing?

Bejarano: The biggest limitation right now is getting the fishing licenses in order. The fishermen do not trust the government so some do not get licenses. They tend to stay away from the government and go off on their own. It’s like a small country here. They each have their own president municipal, like a Mayor. It’s a limitation for them and for us because we cannot ship our local catch because those fishermen do not have the license needed to create an invoice.

Villareal: If they can’t provide us with an invoice, we can’t supply it. We supply our fishermen with permits from Ensenada.

Are there other regulations to fishing? Can anyone go out and just fish?

Bejarano: You would need a fishing permit for sports fishing; it’s about $10 per day. You can’t just go out and fish––the Navy is checking the boats. What they’re bringing, what type of fish you’re carrying and the merchandise you’re carrying. Like the sea urchin right now cannot be caught right now.

Do you see any specific issues with overfishing in Popotla?

Bejarano: Yes indeed. We are seeing a strain on the sardine species.

What can chefs and consumers do to help with the problem of overfishing?

Villarreal: Develop menus that adapt to the different fishing seasons so we can begin to control the seafood demand that has been harming our oceans.

We try to use social media and put information out there. Also, our chefs used to just ask for the filets but now we are teaching them to use the whole fish––to use the bones, head, the skeletons, and not to waste. We have to come back to the roots, to the basics.

Bejarano: We are working with culinary schools to help educate the students to use our local fish––teaching them to what we have here locally to help support our fishermen. The students get to come here to Popotla to meet the fishermen and see what is being caught. We are promoting the local catch to the new generation of chefs.

Villarreal: We are also part of the culinary curriculum. It is not mandatory, but it is part of their culinary studies. They get to come down to Popotla to see the fishermen do this without the resources that they have. They have to feel that this [the community] is also theirs. If you don’t support the community, how can we bring them all together?

Bejarano: [The new generation of chefs] need to learn how to select fresh fish. What is a fresh fish? Look at the eyes, look at the skin, smell the gills. Fresh fish doesn’t smell like fish. We try to sell only catch that is fed natural food, catch that is wild. We don’t like to sell cultivated product.

———

Here in the United States, there are organizations, such as Seafood Watch by the Monterey Bay Aquarium, that are dedicated to helping fishermen and consumers become educated about and to practice seafood sustainability, in an effort to help replenish our oceans and manage its resources. Researchers have noted the increasingly important role local fishing is playing, and will continue to play in this struggle to safeguard oceans.

The future of our oceans not only lies in sustainable fishing practices like what Think Blu is promoting, but also in further educating our society about the food that they are consuming. We must rediscover the beauty and value in artisanal fishing, and in the dedication of the women and men that are placing food on our tables.

———

Photographer’s Note: All photos shot on Ektar 100 film stock

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.