“The pleasures of the table are for every man, of every land, and no matter of what place in history or society; they can be a part of all his other pleasures, and they last the longest, to console him when he has outlived the rest.”

— Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste

…

Like most of my encounters, without anticipation, I was invited to dine at the tiny but mighty Chi Spacca in Hollywood. Tucked away under Nancy Silverton’s Mozza empire, and nestled inside the same building that houses Nancy’s legendary eateries, Pizzeria Mozza and Osteria Mozza, Chi Spacca is a kind of secret that everyone knows about. With Nancy Silverton, Mario Batali, and Joe Bastianich behind the project, there is no question about the quality of the cuisine they served.

Through the frosted windows and modest exterior, Chi Spacca’s intensity shines bright with a wood-fire grill and oven that left me mesmerized. Not for its warmth on a winter evening, but for what it signifies in food’s history: at the most basic level, fire—and our ability to harness it—is one of mankind’s greatest accomplishments in differentiating ourselves from animals. With it, the dawn of cooking and all of its opportunities, stem from this one feat. The irony of all this is I had arrived at the beginning of dinner wearing a tailored Ben Sherman suit—as any distinguished gentleman, by way of society’s standards, should—and by the end of dinner, one could describe my impetuous appearance as a ravenous, primal carnivore who feasted on its prey in the jungle.

More on that later.

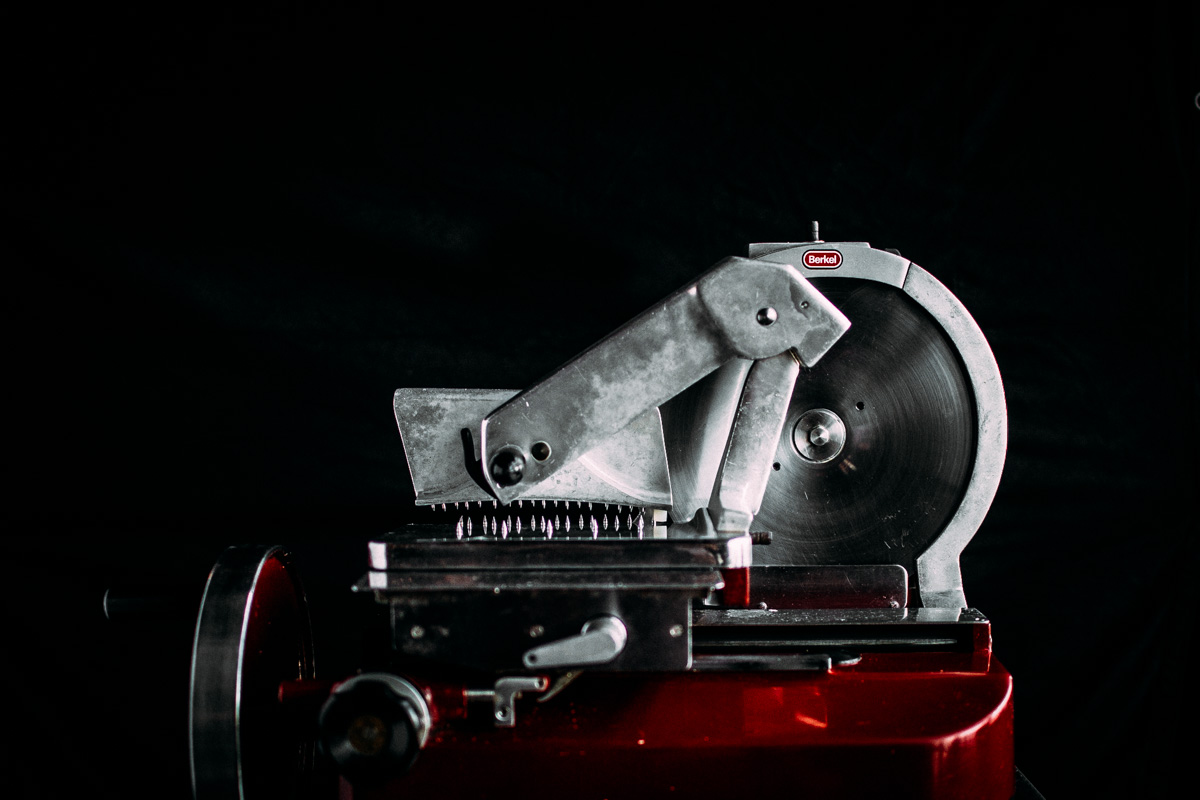

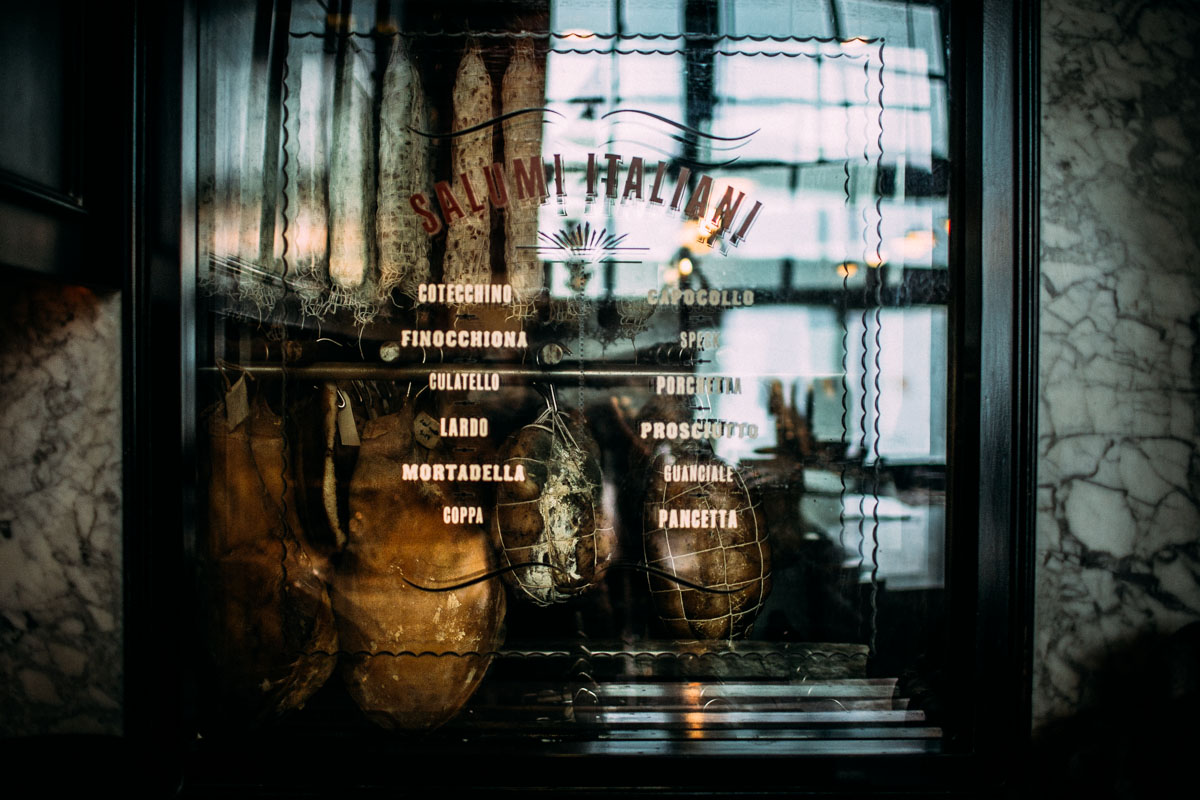

Chi Spacca proves to have a rather atypical history than most, because it was conceived with varying challenges and a rather ambitious goal of pursuing perfection with a meat-based menu, inspired by an underlying foundation of traditional Italian flavors. You won’t find pasta here, but instead: sweetbreads, milk roasted pork loin, beef & bone marrow pies, costata alla fiorentina, whole branzinos, and the king of them all: the tomahawk pork chop—oh, the thing dreams are made of, larger than my head. But the real challenge came with an inhouse salumi program where all of the butchering and curing would take place on the premises.

Allow me to back up, prior to Chi Spacca, a fully certified, fully legal salumi program did not exist in any Los Angeles restaurant. With the LA health department scratching their heads trying to find a certification that did not exist, the small but dedicated Spacca team remained relentless in achieving that ever so fleeting taste of Italian authenticity, for they wouldn’t settle unless their salumi was made in house. And triumphant they were.

A large wall with many, many bottles of Italian wine tower over the tiny dining room that only seats thirty-five patrons. The decor is neither pretentious nor overly rustic, but cozy, warm, giving off the feeling that you’re among family. Sitting at the kitchen bar for a front row seat of the theater of flavors to be bestowed before me, the service staff present each dish on the menu with a passionate story, telling of the intentions behind the flavors and its rich Italian history. It’s mesmerizing to say the least and a gateway for educating the guest. By the end of it, I felt like I had been told a bedtime story about chefs, Italian grandmothers, and… the many carcasses of beef and pork made into tasty, buttery, fatty bites of pure bliss. The mere detail of the overall experience is what excites me about food. For some, it’s just dinner, for people like team Chi Spacca and myself, it’s mankind’s way of finding common ground among foreign cultures.

The dinner concludes with sleeves rolled up, grease stains on my shirt, and a loosened tie. I’m in a daze and the troubles of the world mean absolutely nothing to me at this given moment. All I know is that my taste buds were punched in the face by an unapologetic intensity of meaty flavors in the form of grilled, baked, and cured methods. I wonder if ushering a first date to such a place is a bad idea, or the best idea, because it can reveal the primal nature of who you’re dealing with.

I will spare the details from my own recount of the context one should be aware of upon visiting Chi Spacca (I am still out of breath from the 42oz tomahawk pork chop after all) and, instead, allow the man behind the execution of the menu, Chad Colby, to impart such knowledge.

Chi Spacca. The beginning. What was it?

Chad Colby: The job I was first offered here was to work with Joe Bastianich, working on a wine shop featuring the wines he imports, the wine he makes, and the winemakers he works with. They wanted someone who could cook micro-regionally to accommodate it. They built this beautiful kitchen where that could happen. You could do these private dinners with the winemakers talking and the chef talking about micro-regional foods of that region and pairing them with those wines. They thought I’d be a good fit for that.

As the licensing didn’t translate, we evolved. We did everything we could. We had this big, beautiful room we used as a private event space. We hosted dinners that were family-style and focused on ingredients. I did pizza classes, pasta classes, and butchery classes. Just about anything we could do in this room we tried.

Throughout that process I would have a little more free time than a normal chef in a normal restaurant to do some things and spend some time on some side projects that you wouldn’t normally do in a busy restaurant. Part of that was the cured meat. Part of that was working with the health department and doing it legally, which hadn’t been done in Los Angeles before we did it. That process was a combination of artisanally trying to make something great and working with the health department on what we’d be allowed to do.

What was it that influenced you to pursue cooking?

Chad Colby: A sports injury. I was obsessed with soccer all the way through junior high and high school. By senior year, right as the varsity season started, I had the ball, did a little move on someone, shifted direction, and his entire body weight crushed my knee; I had severed my ACL.

Throughout that recovery, I completely shifted my attention, my passion, my focus to something else. Part of it was being at home—there were no DVRs back then—being hungry and watching the Food Network. It was right when there was this nucleus of great chefs making great food on the Food Network. I was hungry, I was excited, and it was something new for me.

Was there a certain direction you wanted to go in? Or were you hungry for learning everything and then honed in your skills for a particular direction in food?

Chad Colby: One thing I think you need—not just in American or Californian cooking—is the ability to realize that we’re not really rooted in tradition: you’re free to pursue any direction you want.

In Italy, for example, you can’t step outside of tradition without there being a microscope on you. To do something modern and different is to go against the grain.

Here [in the States], it’s the opposite. Here, to do something traditional, with purpose, and with history is against the grain because it’s so easy to go modern. It’s so easy to do something new and to be the equivalent of modern art versus classical because we don’t have that. If I want to do a traditional, classic dish I have to educate people on it. Where in Italy everyone knows these classic dishes and how not only their grandmother makes them, but how their aunt makes them versus how their cousin makes them. You never have to explain what a bollito misto is, or other dishes like that.

|

|

Were there any pivotal moments along your journey that attributed to what you’re doing today, specifically curing meats and cooking Italian cuisine?

Chad Colby: The first real introduction I had was when I was in school—it wasn’t for cooking, but hospitality management. And the direction was to go into some sort of corporate management for a big company. I got a wine scholarship through Castello Banfi and they send twenty students every year to do a food and wine education tour. We went from Piedmont through Tuscany, and ate and drank the entire way. During those tours we were on a bus experiencing beautiful stories, and getting an education about the history of food and wine in the region.

I do specifically remember, on that trip—I extended it and went out on some journeys of my own—eating bucatini all’amatriciana from a famous chef who was in the town Montalcino. He was from the town of Amatrice, where the dish comes from. I remember it being simple, and just so perfect. It was just simple enough where I could look at it and look at the variables and think, “I could create this. And I could enjoy this more often if I did.”

That was definitely an epiphany for me, proving to myself that I wanted to be a chef. I could do this, I could create this, I know these flavors, and it is something I would want to do. Very specifically, I would say that was the moment I knew I wanted to be a chef and an Italian-focused chef. I tried all sorts of cured meats on that trip without ever thinking it was something I would recreate. It’s something you’re not legally allowed to do. Everything needs to be imported. But the difference is they don’t import the ground salamis. The salamis you have in the States are the ones made domestically, and there’s a major difference in how they taste.

I did another trip the next year through Sicily. It was the same thing. There was this nostalgia, this flavor on my palate of great cured meats you wouldn’t get back in the States. Even the other things that are imported are imported through USDA standards versus the Italian standards. There are different salt thresholds and drying and everything else that they want. There was a constant nostalgia on the palate that essentially only became possible to have when I made it.

That was really the inspiration to try and make some of these things. If I want to have something as good as over there, I’m going to have to learn how to make it here.

|

|

I’ve gone back to Italy several times, specifically to try cured meats and get more inspiration. It’s funny how it’s evolved from having something I only enjoyed on the palate and wouldn’t be able to enjoy again, to having things now where I’m not looking to change my techniques, but am looking for inspiration for flavors and tradition. This is how they do this, and I can see a piece of meat and just from tasting it and looking at it, I can make it without asking for the recipe. I can look and see the grind. I can look and see how they bound it. I can taste how long they fermented it. And I can pick up the variables based on that.

I want the story behind it. I want to know how long they’ve been making this here, and why they make it here and not somewhere else. Every once in a while there’s something I can draw inspiration from and I can recreate it and have it be very similar. I’ll keep the name in Italian on my menu. If I twist it and I think mine might even possibly be better, I’ll do an English wording on the menu. Just because even if it’s better and different from home, people will say that’s not a true finocchiona. Maybe I like mine a little firmer with a bigger grind and a little bit of better bind than you’d traditionally get, so I’ll call it fennel salami, that way they can judge it based on the palate, and not its historical merits.

You mentioned you love the storytelling behind the food. Why was it important for you to bring that idea of storytelling and history to the experience of the diner?

Chad Colby: It’s funny to look back and think about this. I did it a couple months after we started. We do have lengthy staff meetings where we talk about dishes in detail. It came out of concern. It came out of making things that are traditional but aren’t typical, that might cross someone’s expectations and could, in theory, be something someone was upset about. We make a dish we’re known for, focaccia di recco, it’s now a staple at the restaurant. It’s a paper-thin, flat, yeastless focaccia. I had to stop people from saying it’s not a traditional focaccia. Don’t tell that to the people from Lecco; they’ve been making that for thousands of years. That is their tradition, it’s just not typical. People don’t know it. It’s not commonly translated here. And it’s also on a pan that could poorly burn someone.

So the first two things were make sure you talk about how it’s not like a spongy focaccia, and it’s on a hot pan. We started working that into some nuance in what the dish is. And we decided there should be a culture of that storytelling, of that experience. People were striving to hear more than just a disclaimer and a warning. It almost stemmed from an insecurity that people wouldn’t really understand it.

What were the challenges in securing the first certified salumi program in Los Angeles?

Chad Colby: There are different laws within state regulation that say you’re not allowed to dry cured meat on premise without a HAZOP plan.

There were plans that were put in place, ways to dictate how food is prepared, which was originally set up through NASA—how to get food in space and how not to get astronauts sick, because there would be no recovery from food-borne illness when you’re in a space suit. So they did these geometry proofs showing how food is handled, how it can possibly be contaminated (biological contamination, physical contamination or chemical contamination) and, at any possible point where any of those contaminations could occur, you have to be able to identify it and see how you would either fix or discard product. It’s something that has been adapted to for all large-format production of foods in different elements. You need it to commercially make pickles.

All these things need proof, and it’s particularly under the microscope when you’re working with something people are scared with, such as raw meat that isn’t cooked and it’s held at refrigerator temperature. And then it gets worse: it’s pork. And it gets worse than that: it’s in an anaerobic environment, something where botulism could occur. And it really is something where if the science isn’t taken seriously, if you’re licking your finger and holding it up to the moon, and deciding if you’re going to make salumi, that might work in certain towns where they’ve gotten away with that in Italy, but you need to know whether or not there are botulism spores potentially in a batch.

It was really difficult to find something that would apply to such a small space like we are. Everything we’d find in our research was geared more towards a large production plan. There were things that would be common in how the code of salumi making would be made that was blatantly written for equipment that was not within our size.

If there was one thousand pounds of meat going through this thing per hour, you would connect these different things to it. There was a point where they asked for constant temperature in the room for fermentation. I’m making a ten pound batch of salami in a chamber, and if I open the door it’s going to change a degree. They were like, “Well, it needs constant temperature for what we’re reading here.” I would need these networks of safes that go into the center of the perfect constant temperature room. It didn’t actually reflect the validity of the science of how it was made, so I had to prove how fluctuation of temperature during fermentation was allowed. And we had to document all that stuff. There was a lot of back and forth.

This was also something very new for LA’s health department.

Chad Colby: The health department could have easily—and other cities have done this—said, “No dice, we won’t even look at it.” They knew how excited and how much work had gone into it, and there must have been some interest to see how it would go. Whatever it was, they allowed for the idea of it to be pursued. One thing was I hadn’t served it to the public, I had already sent out samples to a lab proving it didn’t have pathogens, and because my curing chamber is isolated and separate—we had introduced it to them as being essentially quarantined—and we were looking to work with them symbiotically to see if we could pursue making it and serving it.

The Health Department, having us present to them, decided that they would analyze the program. They had never analyzed a HAZOP for cured meats, so they brought in a consulting team. And that consulting team had never analyzed a program for cured meat. They didn’t have any other health department guidelines to use to analyze it. Because it has to be within California code, they couldn’t look at other states. They decided to hold us true to the policies in place for a USDA facility. That means a lot of scrutiny. With the exceptions of the build-out, which we don’t have, it’s completely different than how you would conceptualize a plant to make your meats versus what’s in an existing restaurant. But the technique and the practices and the standard operating procedures needed to be at a USDA level.

Food can be a really powerful tool. It can be a conversation starter for sustainability, fair practices, and even for future restaurants and programs to look at Chi Spacca to move forward. Are there some issues or challenges you’ve seen now in the meat industry that might be overlooked by the masses?

Chad Colby: I guess some of the concerns and the issues of meat like whether it’s ethical and the quality of it are things that have been really highlighted recently. Probably one of the most influential books of my career was “The Omnivore’s Dilemma.”

It came from a place of the things I had opinions on, I didn’t really have the authority to talk about in my mind. And it wasn’t written by a chef. It wasn’t Bourdain rambling, swearing and ranting about things, which has also shaped my career and the way I think about food. But it was a botany professor talking about the science behind it and what was actually happening, and really acting as an investigative reporter in regards to some of the things he wrote about. It was really interesting, eye opening, and shocking.

I don’t necessarily go the exact path of full sustainability. This place has never really been perceived or marketed or sold as in that direction. It’s something I strive for and look to embrace and feature in the restaurant. But the restaurant is a place you go in and have a beautiful meal. And it’s something you eat on your palate, which is something I’ve always kept in mind. I try to, as much as possible, have that be something that involves things that are not only delicious, but well-raised.

The wine list is an entire Italian-only wine list, so that’s not local. These bottles came over on a ship. But I don’t necessarily want wines within 100 miles of here served on the menu. There’s also the element of is it a wine we love and enjoy and we think is perfect for this room. And is it made beautifully in the bottle where it came from; that’s important.

I work with what I truly believe is some of the best pork in the country. And it’s coming out of places that I think have true terroir for pork. We’re working with farmers who are out of Kansas and Iowa—places that don’t have a Chez Panisse across the street from them. They maybe have a truck stop across the street from them. And if they’re not making this product that is going to the coasts, it’s not being produced. They’re going commodity.

The beef program as well. We do prime Black Angus. It’s a program of cattle that’s been grass-fed, and then finished on a corn-fed 120-day diet. We’ve gone through and worked with the company, looked at videos and everything else through the entire process. It’s something that is a combination of striving for that natural product, but also they’ve put a lot of attention into how they corn finish them. It’s not straight commodity corn; it’s the entire corn stalk. It’s filled with alfalfa and all this other stuff. The farmer can grab a handful of it and eat it and say it tastes like granola. And then on the palate the beef’s better for it. It’s an amazing product.

There’s amazing grass-fed beef that’s fully grass-fed. It’s also seasonal. It’s also inconsistent. I want a perfectly consistent steak year-round in the restaurant, so I look to have elements of that. I strive to get as close as possible to something that’s perfect. But I never want to stare someone in the face and say, “The reason you don’t like your steak is because you’re not supporting my ethics.” I want someone to eat a perfect steak.

There is an interesting pull in that direction of the products that we work with. Our chicken program is incredibly sustainable and also interesting in that the birds are processed the same day that we order them. That proximity to soil and the proximity to the slaughter makes an incredible affect on the quality.

|

|

What advice would you give to aspiring chefs who don’t necessarily want to become a cookie-cutter chef but might want to do something special and take risks?

Chad Colby: I’ve always learned to not cook with fear and cook to my palate, and in a sense cook selfishly—cook the food I want to eat—and think about the dish and how I want to enjoy this. Not how I want it to look. Not how I want it to pair. Is this something I crave and I want to eat? When I keep that in mind, I’ve never had a hard time serving anything and having it not be received. Whether it’s offal or a new type of fish or anything different or that’s not typically served, as long as I put myself in the mindset that this is something I really would enjoy it’s gone over well.

The insinuation with L.A. cooking is, “Are you cooking steamed vegetables, tofu and all this stuff?” The [Chi Spacca] menu is about as brash as you can get with the style of food that we do. And you look at some of the other best restaurants in the city and they’re rooted in brash cooking that is full-flavored, doesn’t apologize for what it is, and features items that could be deemed challenging on the menu, but are beautiful on the palate.

—

Chi Spacca

6610 Melrose Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90036

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.