Just south of Colorado Blvd in Old Town Pasadena, CA, before Arroyo Seco Parkway converts to the 110, there is a small shop located in a small industrial building with a roll-up, warehouse door. Its facade is simple and unassuming, but through the door is a tiny factory producing what most think is an anomaly in today’s food system: local whole grains milled into fresh, natural, and sustainable flour using a wooden, stone mill.

Welcome to Grist & Toll, an urban flour mill.

The flour and wheat industry is a complicated machine that leaves little room for small-batch artisans and wheat growers since the majority of production is controlled by corporations and the industrial food complex—it’s a “join us or good luck” sort of thing. Whether it has become a trend or just a marketing ploy, “farm-to-table” has created an awareness about where our food is coming from and has made shoppers and diners more conscious about their food-buying decisions. However, this mentality mainly scrutinizes the sources of meat, veggies, and dairy—not so much flour. In fact, flour’s bad rap only got worse with the gluten-free movement. Wheat-based flour just can’t seem to catch a break.

In a way, food culture in the U.S. is moving backwards in time and we’re relearning how things were in the past. Sustainable practices, fresh and local produce, and happy cows are new and hip now, but that’s simply how life was before everything got so muddled by industrial practices. Now we’re taking baby steps to rectify the situation and revert back to a more natural system. Flour might take a little longer to get there, but there is a glimmer of hope with people like Nan Kohler, founder of Grist & Toll, who is taking the risk and leap of faith to change people’s perception of flour by redefining what “real” flour is, with all of its nutrients intact.

Before venturing into a large, white, temperature-controlled room to see Nan’s process of milling whole grains into an aromatic beige powder (never truly white), I sat down with her to hear about her ongoing journey as one of the few artisan, flour millers, and to learn about natural flour versus what is normally found in supermarkets.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Independence, Missouri, just outside of Kansas City. It’s famous because it’s the home of Harry S. Truman. So I grew up in a historic neighborhood halfway between his house and the presidential library.

I moved out here [Los Angeles] with my very dearest and oldest friend. We grew up together, and when we graduated from college we said, “We’re going somewhere.” So we graduated, worked and saved money for a year, got in our cars and drove out.

What led you to the food industry?

I started baking. I’ve been baking my whole life. I had a friend who was managing a farmers market. She said, “I don’t know why you’re not baking professionally. You should be baking.” Everybody has a friend they tell that to. I would tell everyone, “You’re crazy. But thanks, I’m glad you’re enjoying the sweets.” And this time she was like, “A space is here if you want it.” And I thought maybe I would be silly to not explore it. So I did.

I found a commercial kitchen a caterer had that I could sublease, and I launched my own little brand at the Studio City Farmers Market. And from there, I met Leslie Denelian, the owner of Sweet Butter; she was a long-time caterer and was about to open her first restaurant in the Valley. She came and tried my baked goods and started hiring me to do desserts for her catering events. From there, it was, “Will you come to Sweet Butter and be the baker?” and helped me launch this business. That’s when everything became more official. It felt legit.

So as a baker, you began working with flour. At what point did you decide to make your own flour?

It’s kind of an “out-there” endeavor. I think about it now… when I look at me today and see the business, I’m not exactly sure how I got there. I just kept asking questions, making decisions, and things started falling into place. All of a sudden I had a business and things were up and running.

But fundamentally, as a baker I’m very curious. My style is never overtly sweet, one-dimensional sugar bombs. I find that very boring; I’m not interested in it. I played around with ingredients and was naturally drawn to looking at different types of flour. So at the most basic level, it all stems from that, and me saying, “As a baker, this is my most important ingredient. Where is it coming from? How is it being produced? What about all these other flavors and things that are out there, and how do I get them?”

When you think of the farm-to-table movement, you think of vegetables and meat—not so much flour and wheat. How do you jump start a business like that?

It’s complicated. I laugh at myself now, because now I’m up and running as a real business, buying grains and milling them. But in the grand scheme of things, there’s a lot that’s much more complicated than I ever anticipated. You think you’re going to buy grain and you’re just going to mill it and sell it—easy peasy, life is great. But because everything has been so removed from our immediate society and our culture, and it is so huge and corporate, a lot of the fundamental infrastructure for things I am interested in and things I think are important for wheat and local grain economy are gone. And those will have to be built step by step.

I want fresh flour, I want local flour. As a baker, I want to be able to go to the mill and talk to the miller and have conversations about what I’m baking, what I want it to taste, look, and smell like. So question number one is: what’s the deal with wheat? Where are you going to get wheat? And how accessible is it? And California does grow wheat—a lot of wheat, some beautiful wheat.

One of the biggest challenges for me is that I’m so tiny. A lot of those bigger corporate farms and seed handlers are the distribution arm of the agricultural world. I’m so irrelevant to them. I’m one grain in a one-ton tote. When I first started having those conversations it was, “Really? Don’t you need two truckloads?” They’re not used to cleaning and bagging and selling products to smaller endeavors anymore.

So first, it’s a network of trying to make those connections. Who will do it for me? And I found some definite allies along the way. We actually have a California Wheat Commission with an amazing executive director, Janice Cooper, who’s been helpful to me in making a lot of those key connections. So where there’s a will there’s a way. If you just keep asking the questions, if it’s important you’ll figure out a way to make it happen, through perseverance and finding the right people who will ask those questions and help to make something happen.

I’ve also had to come to terms with—and I knew this pretty early on—that it’s going to take a while for a business like mine to be using 100% California grains. And I don’t know that I’ll ever get there—not because I may not ever have the opportunity down the road, but partly because of my nature. I’m an explorer. That means if I hear there’s this amazing grain or someone is growing something really cool and I can get a little bit of it, then I’m going to be all over that. I’m going to want to mill it; I’m going to want to offer it to people to bake with it. We’ll see what the percentage is and what the spread ultimately will be.

Tell me a little about the wheat you’re sourcing from and where it comes from.

It’s a lot of California-grown wheat. I have a few things—like my Sonora—which is heritage wheat and historically important to California. I actually get it from a farmer in Arizona because I don’t have it available to me here. There are a few farmers in Northern California who have been growing it for a few years now, but their quantities are small. They have enough for their immediate market. They have enough for their CSA business. But not enough where they can sell down here in the Los Angeles area.

I’ve been working very closely with a farmer who’s become a personal friend of mine on this journey. He’s a fourth-generation farmer. I met him up at the grain gathering up in Washington State, which they have every year. He grows beautiful grain that he mills himself and sells to his area very successfully. When I first approached him I said, “Look, there are two or three things I really, really want and can’t get. And I know you don’t have to, but would you consider selling to me?” And he has and we’ll continue doing business together because his product is excellent.

The most important thing for me is if I can’t have them in my backyard, I want to know who they are. I want to have a relationship with them because this is very much about a long-term partnership and business where ultimately I’m going to say things like, “I discovered this. Would you plant five acres?” That’s best-case scenario.

What is different between Grist & Toll flour and what you find in the supermarket?

It’s dramatically different. I hesitate to say “old world” and “old school,” but it’s very much a purist’s thing. I really want these products to be new and modern and relevant for the cooks and bakers today. My process is called whole berry milling. In corporate milling, the whole goal is to get to white flour. They begin with tempering the wheat—cooking it in some sort of a liquid; it could just be water—and they want to pop off the bran and the germ so they can get to all the white endosperm and culture of the wheat berry. And all the flavor and nutritional value—there’s a tiny bit in the endosperm—the vast majority resides in that bran and germ. It means that inherently in that process—which is pretty volatile—sometimes that endosperm is exposed to heat, high temperatures, bleaching, and all sorts of things happen.

In the grocery store, if you buy whole-wheat flour, it is a reassembled product. They take the bran and the germ—who knows how long it’s been sitting. That’s where the minerals and oils are, and they’ve begun to oxidize. And they just add portions back in to make a “whole wheat flour.” It’s not such a natural process and there’s no real regulation on what makes something whole wheat or whole grain. Pretty much stone milling and whole berry milling is the only way to get that.

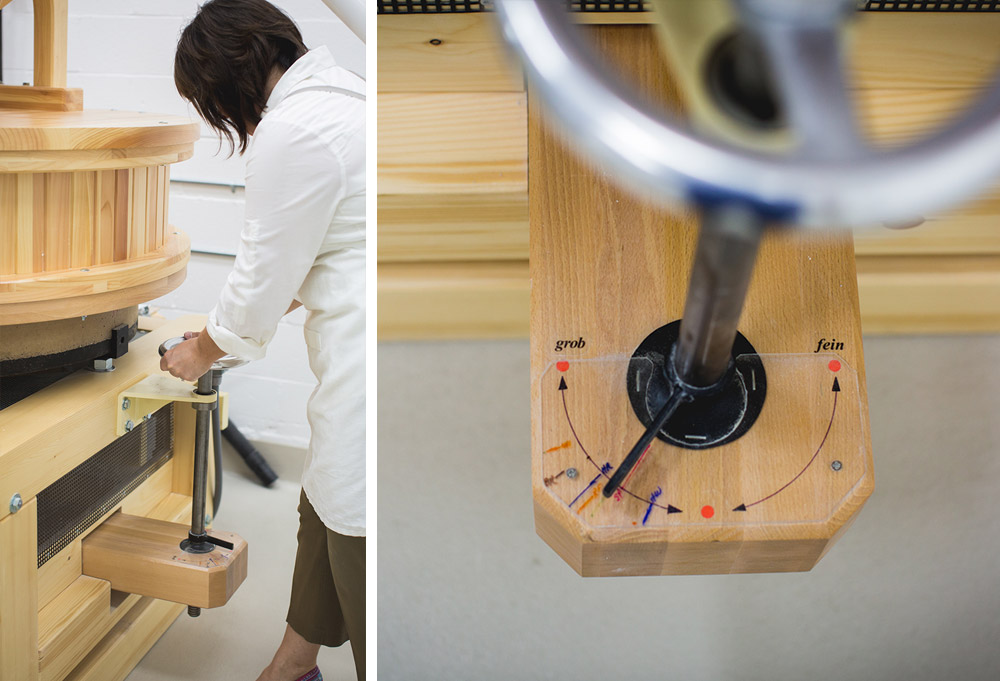

I have a stone mill. I’m whole berry milling, which means I’m not separating the bran and the germ from the endosperm. I don’t temper it. The berry goes into the machine, I have my setting and controls on the grain for how I want it to look and feel and what its baking properties are going to be, and that’s it. Right now I’m doing what the industry calls 100% extraction flour, or whole grain flours. It means every single component of that wheat berry has been extracted to make the flour.

I do have a sifter. So if I want to do what is known as high-extraction flour—which means some percentages of the germ have been sifted out—it’s there for that. I was thinking in the beginning I might need to do that because whole grain and stone-milled whole grain is so different than what we’re used to seeing and working with, that I thought I might need something to help wiggle me in. Except I’m finding that’s not really the case, which is great. But, I’m curious and I’m going to want to tinker around, play with some things and see how it affects the baking or the outcomes. So it’s there for me to play with and see what I want to do.

My flour looks very different. I’ll never be able to create white flour. The rye has a blue-green ashy quality to it. Sonora has very pale colored flour with little golden flecks from the bran and germs. Spelt is a little nuttier looking and smelling. They all have very unique colors and textures. I tell people the first thing they’ll notice if they open a bag of my flour versus something off the grocery store shelf is it actually has color and aroma; they smell dramatically different. All of that has an impact on whatever it is you’re baking.

Tell us a little about the actual mill you use.

The vast majority of these machines are traditionally are sold in Europe. In Europe, in large-scale bakeries, many of them still mill for themselves. They have kept that tradition, where we have lost it.

Another thing that was important to me was I wanted the stones horizontally placed. There are a couple examples where they’re vertically placed. In the milling process—stone milling, whole berry milling—heat is your enemy. So everything we can do to keep that process cool and controlled is a good thing. We’ve tricked our machine out a little bit to help in that endeavor. And I was convinced after what I’ve seen and the people I’ve talked to that having the stones set horizontally would make a difference, especially if I wanted to slow the stones down, which helps keep the process cooler.

In an ideal future, how would you like food culture to look? Especially considering you’re passionate about the farm-to-table movement.

It all mirrors this shift and these baby steps we’re talking about. And it’s a natural business and life cycle. Things get a little blown out of control, and people want to pull it back in and be a lot more hands-on. I want to make my personal stamp; I don’t want a generic product in 50 other states. I want something that speaks of me and where I am and my community. I hope we continue to build consumer awareness that products and businesses like mine are out there and coming up in the world, and that it will continue to matter. Right now, it really matters. The farm-to-table movement is relevant, and people understand the importance of understanding what’s in the food we’re eating, where it comes from and how it’s handled.

I think that’s only going to become more important because now we’re starting to examine and we’re getting a lot of surprises along the way. And that’s good, because that education makes us smarter and gives us more power in our buying decisions. And that’s how we all affect change and build something that’s long lasting.

The farm-to-table movement is relevant, and people understand the importance of understanding what’s in the food we’re eating, where it comes from and how it’s handled.

If you think back to your childhood, what is that one dish or meal you can always think back on and feel nostalgic about it?

First of all, I have two really excellent bakers in my family. My paternal grandfather, who came over from Germany, was a baker. My mother is an excellent baker. I learned to bake from her. So my grandfather, every Saturday of the world brought over a braided loaf. I would give anything to have that again. No one in the family has the recipe. When you were a kid you were, “That same old bread again? I’m so over this.” And nostalgic adult now is like, “What an idiot.” I can’t believe none of us ever wrote that down. I know it was some sort of enriched brioche/challah-type bread, but there was something a little different about it…

—

Grist & Toll

990 South Arroyo Parkway, Suite 1

Pasadena, CA 91105

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.