Op-Ed

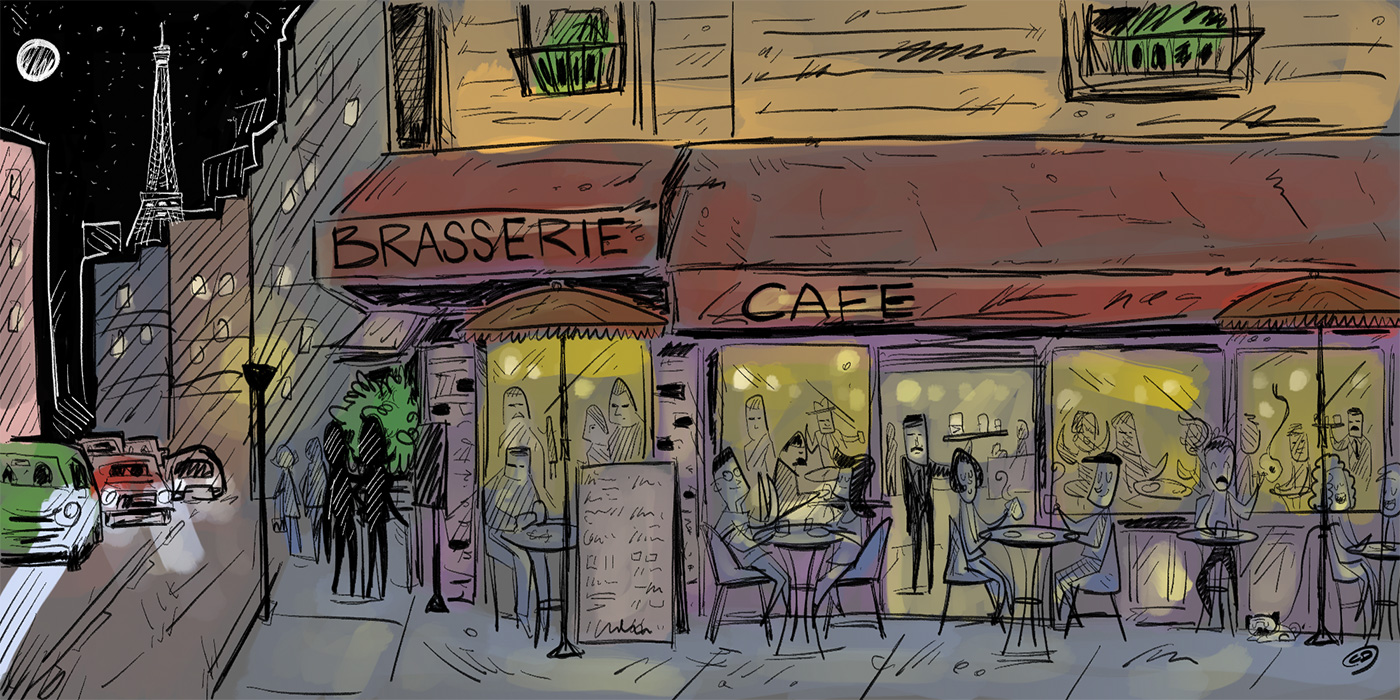

The scene takes place in a small, busy Parisian restaurant a few stone-throws away from the banks of the Seine, not far from the Assemblée Nationale (France’s Congress). It’s Saturday night, and like every Saturday night, it’s packed. People are pressing themselves along the long, shiny zinc bar, drinking Morgon by the glass while waiting for a table. It’s 10:30 p.m. and the curb in front of the door is filled with patrons smoking cigarettes between courses, the ever-present wine glass dangling from one hand. Amidst the laughs, the music, the long-legged Parisian girls and their cotton-scarf-wearing dates, a couple enters and goes straight to the end of the bar where the owner oversees the placement, orders and bill-payment of the human flood contained by the eatery’s four walls. Their exchange is short, but to the point.

“Hey, do you have a table for two?” asks the blonde, fur-collared girl of the couple.

“ Do you have a reservation?” answers the owner, while opening a bottle of Condrieu.

She takes a short breath and answers, “Do I look like I have a reservation?”

The owner raises an eyebrow, not even making the effort of meeting the patron’s eyes, and answers, loud enough for the whole bar to hear, “ I don’t know, but you sure look like someone who’s not going to eat here tonight.”

This exchange might sound outrageous, but this is business as usual in many French restaurants. I know; I’ve worked them.

This exact scene took place while I was tending bar, handing out bottles by the dozen to the loud and rowdy crowd of regulars and tourists who comprised the bulk of our clientele. We served pretty okay French food; it was heart-warming, no-fuss grub. But we had a great time doing so, and observed a silent contract between server and customer. We aren’t here to serve you; we’re here to try and have a good time—possibly with you.

This was true for all the restaurants I’ve been a waiter or barman at in Paris, and there was an understanding that this was okay because regardless of our informal manners, the service was top notch. It was fast, efficient, and dictated by rules that felt more like a code of honor than anything else. God have mercy on you if entrées arrived before you had served wine and beverages, and you’d better not have forgotten the bread. A table in your row where main courses and cheese were finished but still sported a salt shaker or a pepper mill made you the laughing stock of the restaurant.

It seemed the French waiter’s creed: Service is the source of pride; customers are collateral damage.

French people as a whole are quite wary of over-zealous, friendly service, like what they perceive is found in the U.S. The general feeling is this: “We do not know each other on a personal level, so please don’t ask me how am I doing today. I know you don’t give a rat’s ass, and neither do I.” And believe it or not, this isn’t perceived as being rude, but rather dispensing with unnecessary niceties. French customers don’t feel the need to know their waiter’s name and have a formal introduction—it feels fake and forced. For a server, this is a job—one centered around craftsmanship and excellence—and doesn’t require a stranger’s family history or observations on the weather forecast.

This informality in service lies at the heart of the relationship between a French restaurateur and their clientele. When speaking with someone like Loïc Martin, owner of MARTIN Boire et Manger, a lively (and mind-blowing) eatery a few meters from République, he explains that many restaurateurs view those who come to dine not as clients, but guests. They view their restaurants as an extension of their homes. He also explains that the most significant difference between Anglo-Saxon and French service lies in the tipping culture. There is less of a need to be overly amicable when you have a fixed salary. That’s not to say servers don’t want to be excellent hosts, however.

But bear in mind: French-style service’s aloofness (and sometimes downright rudeness) is rarely unsubstantiated. If your waiter is mumbling under his breath or giving you the stink-eye, chances are you crossed him or her in a way only French men and women can be crossed. Reasons include but are not limited to: ordering a Diet Coke with what is considered to be an exquisite meal, asking for ketchup in a bistronomie restaurant, or the most unforgivable of outrages: requesting your meat to be served well-done. If a French waiter is rude to you, most of the time, it’s because you’ve offended French savoir-vivre in some way.

In a world where everything seems to be leveling up to a certain global standard in which the client is king and always right, you just have to remember that the client is rarely the king in a French restaurant. Cuisine is and will always be.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.