The Oakland airport is quiet when I step off the jet bridge and into the terminal. Waiting for a car, San Francisco is out of character for a late summer day; the low cloud cover that usually haunts the city is nowhere to be found.

It’s a slow ride into the city from the East Bay, and I wonder how the 300-mile trip from Burbank can feel shorter than this 12 or so. The highway dips into neighborhoods as we approach the Mission just shy of 14th Street. Trees line the streets as we speed up Valencia Street, past commuters on bicycles and patrons pouring out of cafés onto the sidewalk.

The building that houses Bernal Cutlery used to be a mortuary before taking on a new life as the Valencia Rose Restaurant and Cabaret. Painted green now, it almost blends into the verdure.

As I cross the threshold, the smell of wood makes itself known. It’s not damp in the way a lumber yard smells, or astringent like the back of a hardware store, but is instead rich and warm with age. Before I can find the source, the entryway unfolds into a pantry of sorts. The walls are lined with dry goods and seasonings, tinned fish and vinegars. It’s enough to stop me in my tracks for a moment, before the glisten of a blade beckons me further.

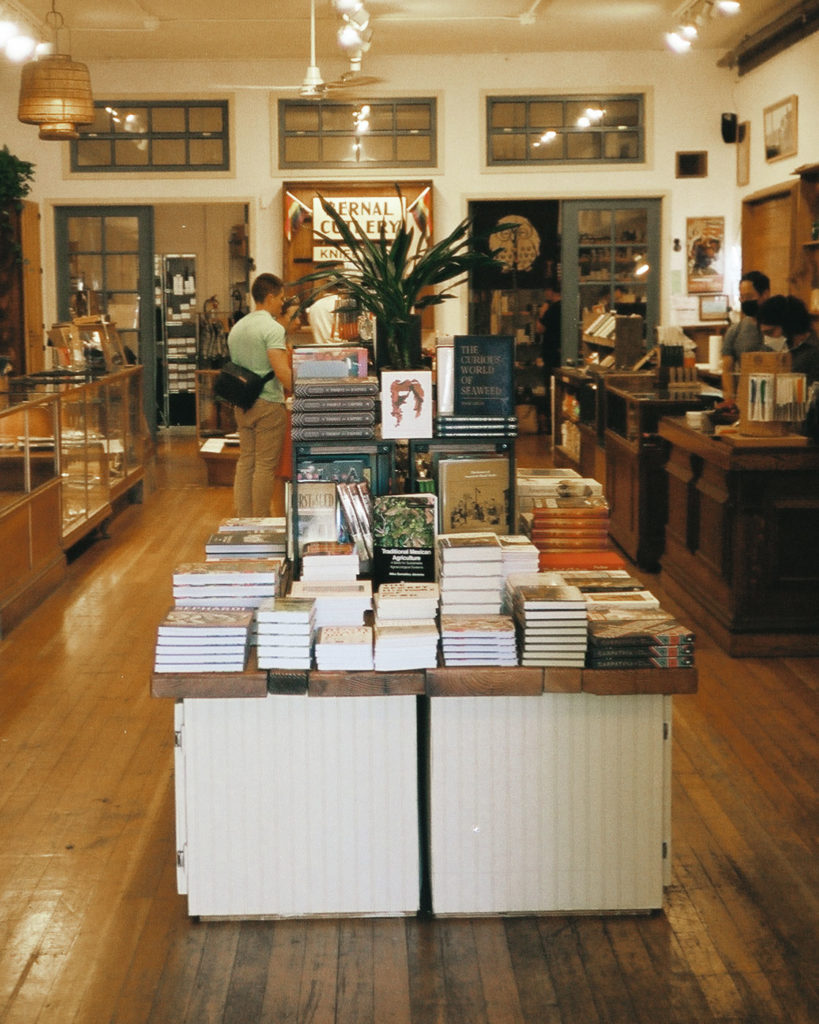

Stepping into the primary room of Bernal Cutlery, I’m rewarded with an answer to the source of the scent that caught my attention. Wood floors meet wood cabinets that point the eye upward to knives floating on the walls. I know their defiance of gravity is a trick of science, but at this moment it feels as though they could be holding themselves up to put on a show for customers who have come to admire them.

From across the hall comes a rhythmic sound of metal against stone. A glance around the corner reveals it’s the sharpening counter. Co-founders and partners in life, Kelly Kozak and Josh Donald, are on the floor with customers when I arrive. Behind the counters, they’re engrossed in separate conversations.

I’m then led through the sharpening workshop and up a staircase to the second floor by Tim Ferron, whose roles include, but are not limited to, brand managing, merchandising, and acting as senior sharpener. At the end of a long hallway before we turn into a storage room, I notice the first remnants of the building’s past life as a mortuary. A long ramp takes up the back of the space where bodies used to be transported. Now, it’s an art gallery.

Ferron joined Bernal Cutlery almost nine years ago. He was living in Orange County working as a cook at Disneyland, but his dissatisfaction with the job drove him to take an offer at a butcher shop in the Bay. He started at Avedano’s in Bernal Heights and quickly took an interest in butchering whole animals, but his beat-up chef’s knife was no match for the work. As fate would have it, Ferron was sent to Donald to buy new knives.

At the time, Bernal Cutlery was only a booth in a shared space on Cortland Avenue. But Ferron kept returning for new knives or sharpening old ones. He got to know Donald and Kozak, and when the opportunity to join Bernal Cutlery as an intern came, he took it.

Before Ferron can say more, we’re interrupted by a knock at the door; Kozak enters. She tells me how she was practically raised in the restaurant industry. As an unhoused teenager, it was the best way to get a job. She would do mostly front-of-house work, and often held two jobs up until she married Donald.

When Kozak and Donald had their first child, she was working as a freelancer on photoshoots. Although the money was good when it came, it was impossible to rely on. At the time, both Kozak and Donald were a couple years sober and in recovery. This moment was a chance for them to start their lives again.

Donald gained a reputation as someone who could sharpen pocket knives, so Kozak put together a flier advertising sharpening services and took it to their local butcher shop.

The business started slowly as Donald taught himself to sharpen. Doing all the work on a single stone, he would make around $3 an hour. But it became a sharpening speakeasy of sorts, with people finding out by word of mouth and dropping their knives off at the old Victorian Kozak and Donald were living in. They then started selling antique knives they found at a local flea market and would restore.

In 2010, Kozak did her last photoshoot and Bernal Cutlery moved into its first storefront on Cortland Avenue. They were part of a collection of other shops that shared kiosks in a space in Bernal Heights and spent three years there before moving to Guerrero Street in the Mission District, and finally their current home, 766 Valencia Street.

Their storefront is a stark contrast from where they started, but it comes with some bitterness for Kozak. The Mission was the first neighborhood Kozak lived in when she moved to San Francisco in 1997, but it’s practically unrecognizable now. By 24th Street, lowriders still cruise down the streets and street vendors surround the BART station. But here, the neighborhood feels sanitized.

Kozak remembers the first wave of gentrification that hit the Mission, and when the first dot-com moved in. She tells me about the shift she saw looking for an apartment when people started to show up with checks for the entire year of rent, making a point to emphasize the violence of these changes.

“I know what it’s like to experience medical discrimination,” Kozak says. “I know what it’s like to be food insecure. I know what it’s like to be a kid with a mom who doesn’t have a place to live.”

“It’s not lost on me that the street outside is a street I used to be a junkie on,” she continues. “And every time I come to work, I come to work on that same street and I walk into this place of abundance with beautiful people in it that don’t know that about me.”

Kozak doesn’t speak with anger or resentment as she recounts her experiences. Instead, she describes the empathy and understanding of her surroundings she now has as a privilege. She involves herself and Donald with the community in whatever way she can, from teaching knife skills classes at high schools to supporting organizations that offer job training to the unhoused population.

“I just think the most respectful thing you can do is know your surroundings and come from a place of deep humility,” Kozak says.

Donald filters in the room, and what immediately strikes me is his steadiness, in tone and temperament.

He retells the story of Bernal Cutlery, filling in details as he goes. Donald remembers Bernal Cutlery starting with a conversation between two desperate new parents across a dining room table, and tells me about the old school desk he used to hunch over to sharpen knives in the back of their old apartment. He recounts a story about picking up knives to be sharpened while taking his son out for a walk in his stroller, and the first time he met the antique knife vendor at the local flea market.

The Bernal Cutlery story is vast. I ask myself how you can take in the totality of the last decade-plus of someone’s life in just a day. But at every turn it comes back to just two people trying to make it in this world, in whatever way they can. It’s clear this store exists entirely because they never gave up on it.

We head back downstairs to look through the knife cases. I’ve decided it would be a shame to leave without one, even though I told myself I wasn’t here to shop. Donald walks me through the process of hand-picking a knife, asking how it will be used, what shape and length I prefer, how much time I want to spend on care, and more. It’s a slow process, pulling knives out of the cabinet to turn over in my hand until I find one I like. I pick it up and my hand recognizes it as if it’s an old friend. As I say my goodbyes and head to dinner, and then my flight back to Los Angeles, I know there’s still a piece of the story missing.

A few weeks later, I get on a Zoom call with Lisa Weiss, the head purchaser, head buyer, and quality control manager at Bernal Cutlery. As we fall into the rhythm of our conversation, Weiss tells me the story of how she met Kozak in 2011.

Living in Bernal Heights at the time, she was traveling back and forth between San Francisco and Hawaii due to her father’s recent passing. Weiss was working in restaurants, but her shifts kept getting cut because she had to miss so much work. Looking for another source of income, a woman at the restaurant who Weiss describes as “sweet and caring” suggested she look into working in childcare. She offered to shop a resume around for her, so Weiss put one together.

Weeks went by and Weiss heard nothing until she received a call from the woman from the restaurant, who admitted she kept the resume for herself. The woman was Kozak.

So Weiss started doing childcare for Kozak and Donald while they were on Cortland Avenue trying to get Bernal Cutlery off the ground. It wasn’t easy for Kozak and Donald to afford to bring Weiss on, but they made it work. Donald was still doing all the sharpening himself, and Weiss remembers Kozak sitting in the window trying to secure funding for the business while she took care of their youngest child.

When their youngest started pre-school, Donald and Kozak asked Weiss if she wanted to stay on and work at the shop. They just signed a lease for their first true brick-and-mortar on Guerrero Street, and Weiss thought to herself, “I think I would really like to do that.”

Weiss has had her hands on practically everything in the years since, from researching and developing relationships with makers, to learning to sharpen herself. The one or two vendors they started with have since turned into upwards of 30 in Weiss’ hands.

As we speak, I realize the question that has been lingering with me is one that neither Kozak or Donald could answer. I want to know who they are, and not to each other, or as a business, but from someone who has been alongside them for almost 10 years.

I ask Weiss and she pauses for just a moment before answering. “They’re very punk rock,” she says, sure of her words. “They roll with the punches, which is very different from myself.”

These are two people who created something special from will and determination alone. At Bernal Cutlery, they’ve created a space to demystify the world of knives, making a greater understanding of one of the world’s oldest tools more accessible through education. They’ve done what they set out to do at the dining room table where the idea was first born—they’ve made a new life for themselves.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.