A Time for Women

The final chapter of our Prohibition series explores how the phenomenon impacted the dynamic and diverse roles of women in American society.

Prohibition wasn’t just about alcohol.

The 18th Amendment may have officially banned the sale and manufacturing of intoxicating liquors, but as we’ve seen over the last three chapters, that’s only what you get on the very first sip. If you were to distill Prohibition down to its characteristic themes, a discerning observer would find mounting racial tension, growing anti-communism and immigrant ostracism, a push to return to “American values,” deeply divided political parties, the heavy influence of media mass-marketing, and—of particular importance to this final chapter—the changing roles of women in a quickly-modernizing society.

Sound familiar?

While it wouldn’t be accurate to say women caused Prohibition—there’s no single origin for something so complex—it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that without the driving force of women, Prohibition might never have happened at all. And that could have been very unfortunate. Despite the rampant crime and corruption that ensued during the decade, the absence of Prohibition may have cost women a powerful springboard for the rights they know today.

Women are perhaps the most iconic emblems of the 1920s; they’re beacons of determination, ingenuity and revolution. From the petticoat-clad protesters who refused to leave saloon doorsteps to the bejeweled flappers finally able to order their own cocktails at the bar, Prohibition-era women demonstrated what previous generations had denied them and future generations would model after them: the ability to differentiate themselves.

Although not representational of every experience and woman at the time, those who follow are just a few who played key roles on Prohibition’s stage. It would be easy now, as it would have been then, to label these women as falling on either the “right” or “wrong” side of the law. But to do so would halve a picture best viewed as a kaleidoscope.

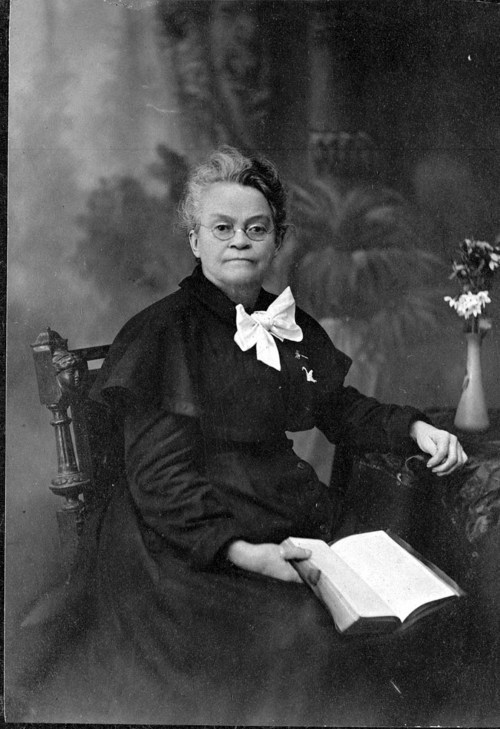

CARRY NATION

To know Carry Nation is to understand the sentiment that eventually passed the 18th Amendment. Most knew her by her hatchet, a small Crandall hammer, and the zealous force with which she’d use it to smash the bars of Kansas saloons and hotels.

Born in Kentucky in 1846, Nation was born into the system of women as wives, and wives as property. After her first husband died from alcoholism just two years into the marriage, Nation remarried and settled in Medicine Lodge, Kansas. As founder of her local Women’s Christian Temperance League (WCTL), Nation felt the weight of women having no legal voice, especially against husbands who squandered every last dime on drink. She advocated hard for Prohibition as cloaked women’s rights, believing that to take away liquor would be to save men (thus women and children) from the workhouse and an early grave.

Despite Kansas becoming the first state to prohibit alcohol in 1881, little was done to curb the popularity of its intake. Through repeated attempts to contact city officials, to reason with local bartenders, even to appeal to Kansas’ governor, Nation realized no one took her seriously. So, she started smashing.

From Kiowa to Wichita to Topeka, few bars in the state were spared Nation’s “hatchetation.” Destroying glasses, chairs, mirrors, bottles and chandeliers, she was eventually arrested—which only escalated the number of female supporters who felt she embodied their cause.

Nation was referred to as a werewolf, a giant, a closet drinker, and even a man in women’s clothing. In time, her following would grow so large she’d be able to financially support herself without a husband by selling hatchet-shaped lapel pins and editing her own newspaper, The Smasher’s Mail. She’d be on the front page of the New York Times and travel as far as Scotland to lecture on temperance.

In her words, “You wouldn’t give me the vote, so I had to use the rock.”

MARIE C. BREHM

By August of 1920, women would have the vote. And on its heels, the very first woman ever nominated for Vice President of the United States.

Although little is known about her upbringing, Marie C. Brehm was an active suffragette and supporter—like Nation—of the WCTL. Her career saw a steady incline through teaching and speaking on temperance, and she was later presidentially-appointed as a delegate to the International Congress Against Alcoholism in 1909 and again in 1913.

In 1920, she became the first woman to chair a national political convention, doing so for the National Prohibition Party. By 1924, and partly to appeal to the newly-established demographic of female voters, Brehm was officially nominated as running mate to presidential hopeful H.P Faris on the Prohibition Party ticket.

In her words, “Organize! Put a whole ticket of women in the field…and you will see the muck heaps of the past cleared away and flowers of a beautified civil life blooming in their place.”

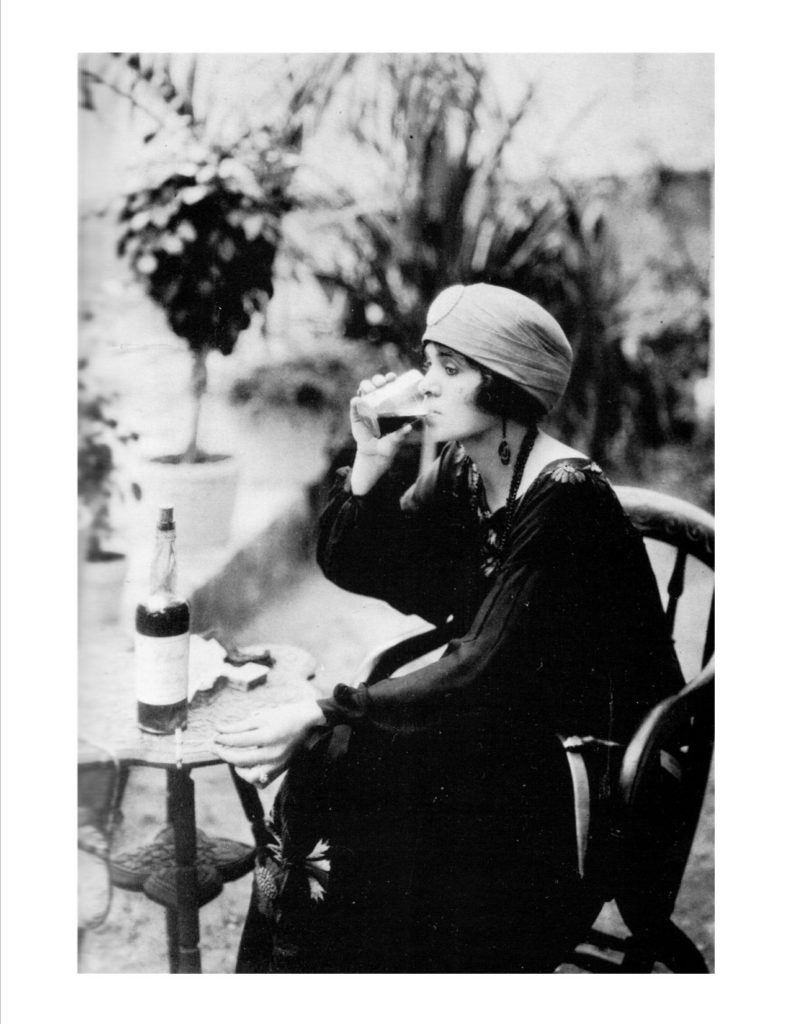

GERTRUDE “CLEO” LYTHGOE

As Brehm rallied for temperance and ran for public office, another woman achieved a very different kind of first.

Gertrude Lythgoe was born in Ohio to English-Scottish immigrants, but earned the nickname “Cleo” due to her striking physical resemblance to Cleopatra. Weathering a sobering childhood—losing her mother at a young age and being the last of ten children—Lythgoe developed a talent for school. She worked as a stenographer in New York and California before finding her way to a British exporter’s stateside liquor office. It was there she became the first woman to hold a wholesale liquor license, which she quickly put to use and moved to Nassau at the start of Prohibition.

Once in the Bahamas, Lythgoe’s charm, unique beauty, and most importantly, wit, combined with her European connections earned her another nickname, “The Bahama Queen.” As rum-running exploded up the Atlantic coast, Lythgoe was able to field the best imports from abroad and gain a reputation through the demand she created.

Rumored to have caught the eye of fellow rum-runner Bill McCoy, the two would never marry. Instead, it was Lythgoe’s steely, gun-wielding personality that backboned her ability to run a successful smuggling business as a single woman in the early 1920s. Although briefly arrested in New Orleans, she was later cleared of the charges and retired in 1925. She claimed she wanted to beat any jinx that was possibly out to get her.

In her words, “Everyone knows that my liquor is the very best.”

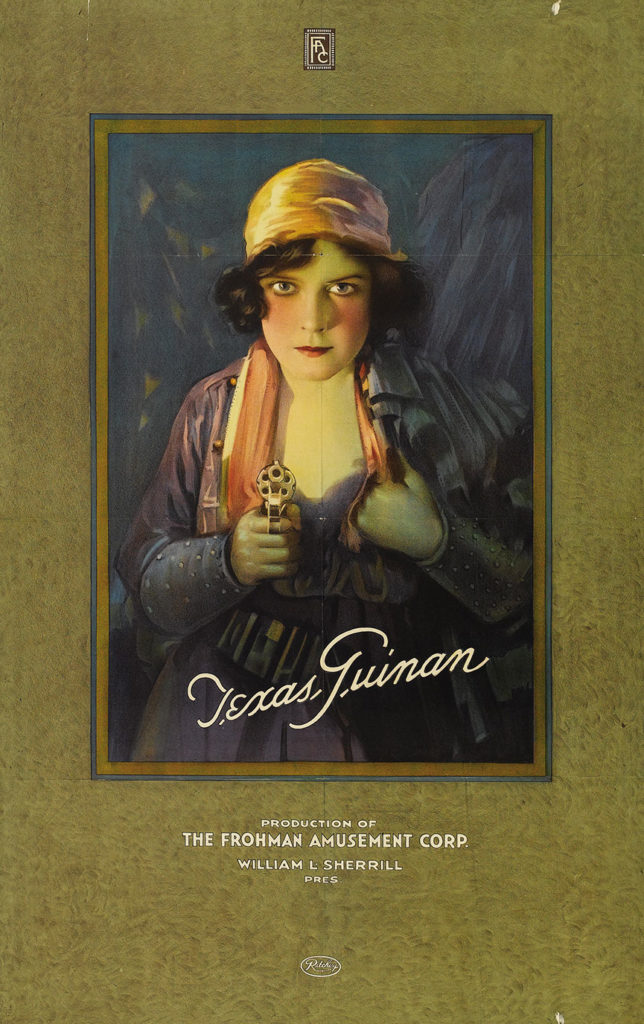

TEXAS GUINAN

As Cleo brought it in, Texas served it up.

Mary Louise Cecilia “Texas” Guinan started as an actress, establishing a tomboy presence in early silent Western films. However, it would be remembering her role as New York City nightclub hostess that would bring over twelve thousand people to her funeral.

During Prohibition, speakeasies in New York were too numerous to count. But plan a visit to any of the most popular ones, including the King Cole Room and El Fay Club, and there you’d find her. A reveler of the late night and armed with years of show-biz street smarts, Guinan made a career out of being a club’s most enchanting center. She had a way of charming anyone, from mobster bigwigs to straight-laced politicians, often through sarcastic remarks, biting humor, and ability to upsell even the cheapest shot of liquor (although ironically, there are reports she herself never drank).

Beginning as a hire of nightclub owner Larry Fay, Guinan was able to bring in close to $700,000 over a ten-month period—the equivalent of almost $6 million today. Before long she was able to finance her own ventures, opening the successful 300 Club and, later, the eponymous Texas Guinan Club, welcoming in patrons for as long as the decade roared.

In her words, “Hello, suckers.”

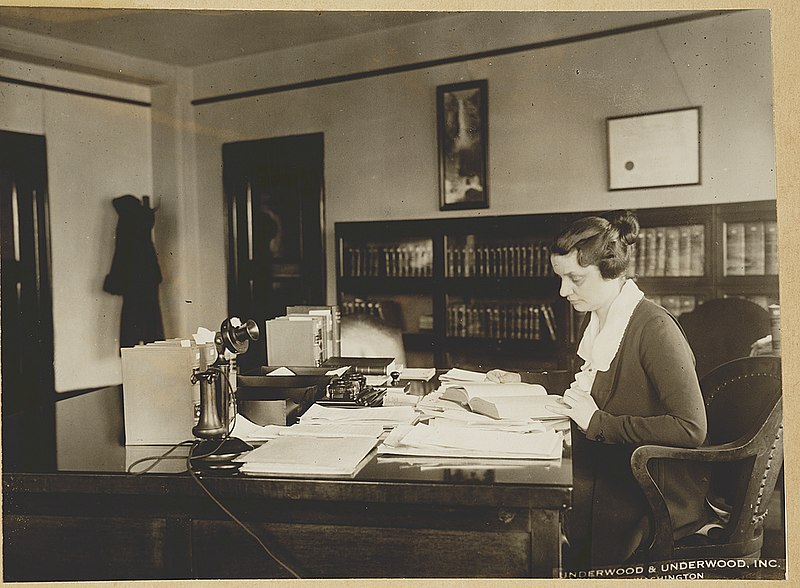

MABEL WALKER WILLEBRANDT

At thirty-two years old, Mabel Walker Willebrandt wasn’t the likeliest candidate for Assistant Attorney General of the United States. Unlike Nation or Brehm, she wasn’t a passionate teetotaler, she wasn’t a member of the WCTL, and she hadn’t even voted dry.

Willebrandt’s advocacy took a different path, beginning as a public defender in Los Angeles working with prostitutes and ensuring male clients had their day in court as well. She later opened her own practice working civil cases with two law school friends; but when a position came up to prosecute Volstead Act violators—a task with arguably no political advantages whatsoever—she was tapped by President Harding for the job.

Willebrandt began in August of 1921 and soon realized there would be little support for her to enforce legislature many officials disregarded after hours. However, she wasn’t easily swayed, even when ridiculed in the press with names like “Prohibition Portia,” “Deborah of the Drys,” and “Mrs. Firebrand.”

As the highest ranking woman in the federal government, Willebrandt put the whole of her ambition into her position, immediately going dry herself and replacing corrupt and ill-suited Prohibition agents with her own team of lawyers. She lobbied the Treasury Department and the Coast Guard to fortify operations against rum-runners and, at a high point, convicted over seventy smugglers in Savannah, Georgia, alone.

When newly-elected President Hoover, for whom Willebrandt campaigned impressively, hired someone else for Attorney General in 1929, she left the Justice Department disheartened and disillusioned but returned to private practice. She’d go on to earn her pilot’s license and lead the way in aviation and radio law, also to represent Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the Screen Directors Guild of America, and movie stars Clark Gable and Jean Harlow.

In her words, “It requires hard work and an unloosening of political strangulation to bring about real improvement.”

Prohibition Examined is an ongoing editorial series exploring the origin and history of one of America’s most infamous eras. Read Chapter I, Chapter II and Chapter III.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.