Editor’s Note: A not entirely comprehensive—but still handy—guide to some lesser and well known cuts. Jered Standing of Standing’s Butchery walks us through the beef shelf at his whole-animal, sustainably-sourced meat shop.

On what I once thought was an early morning, I walk through a spotless glass door on Melrose Avenue into Standing’s Butchery, where owner Jered Standing has been waiting for me since 4:45 a.m. He’s trimming a few steaks, arms decorated with tattoo sleeves moving methodically, tracing his knife along connective tissue with a practiced hand.

As part of a new generation of butchers revitalizing the craft, Standing is injecting some much needed youth and passion into a profession that in recent years has had its practitioners cornered in fluorescently-lit counters, their workspaces and products hidden in the back of chain grocery stores—if not already relegated to shelves of sterile meat packages. What once was a local necessity and a weekly—if not daily stop—for home-cooks, stand-alone butcher shops have all but faded from our cityscapes. Today, the art is slowly making a resurgence coupled with new practices of sustainability. Many butchers are now devoted to managing and minimizing waste, and are conscious of where their animals come from, how they are raised, and what they eat.

Standing explains his vision for this re-emerging craft. “I want to set an example for the meat industry. I know we’re on the far end of the spectrum, and this model doesn’t feed everybody,” he says. At the current rate of beef consumption around the world, switching to locally-sourced, sustainable meat would prove impossible. Through his shop, Standing hopes to educate and promote more Earth-friendly eating. He continues, “If we can just show this really extreme example, everyone is going to land somewhere in the middle, either in their buying habits or when people start selling meat differently.”

Standing’s and other similar shops offer a niche for meat-eating environmentalists. Eating beef from small farms that supply the shop supports farmers who raise animals in open grassland without relying on grain or chemicals for growth. Even if unconvinced about the benefits to earth and animal welfare, flavor-wise, many prefer the pasture-raised animals to antibiotic-laced and fast-fattened conventional products.

Having a personal meat guru on hand has its merits; consider this guide a step closer to a friendly neighborhood butcher, or the finger prod in the back to pick out something new for dinner.

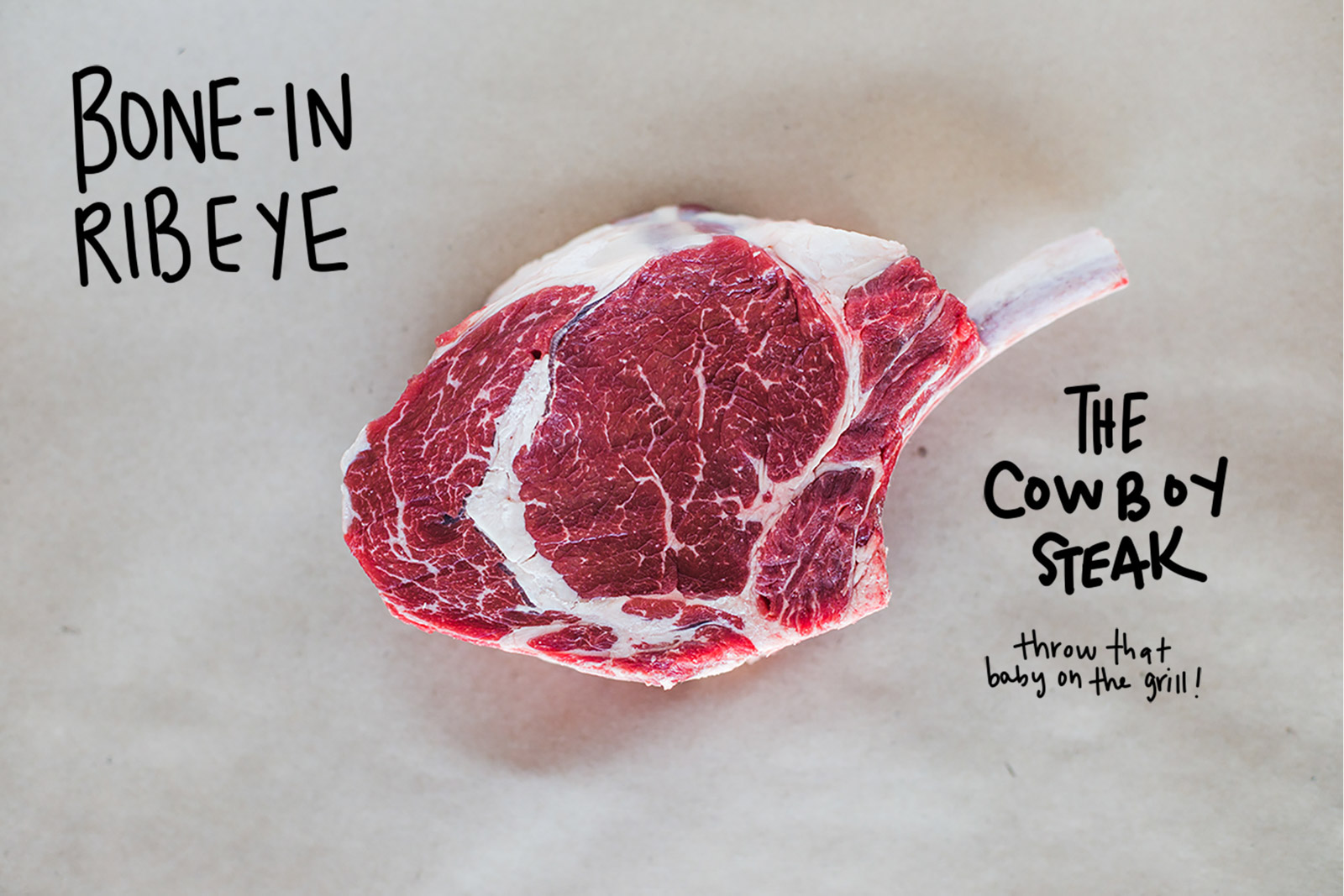

Bone-in Ribeye

The bone-in ribeye has great visual appeal and good value; to account for bone weight, these steaks are generally priced lower than their boneless counterparts. The primary muscle of the ribeye—longissimus dorsi—runs the length of either side of the spine perpendicular to the ribs. It doesn’t get a lot of exercise, and has a good amount of intramuscular fat. The same muscle farther down toward the pelvis makes up one of the two muscles in T-bones and Porterhouse steaks (the other being the psoas major, or tenderloin). True to its alternative name, the cowboy steak is most at home over a cookout fire.

When in doubt: Throw that baby on a grill.

Denver Steak

This steak is better recognized by its bone-in alter ego, the flanken ribs. Sliced thin across the rib cage in the shoulder area, they are often flung over a sizzling personal grill at Korean barbecue restaurants. The Denver steak forms the same muscle, and is prized for its robust flavor, mainly thanks to a high percentage of marbling. It’s a diamond in the rough—a quick-cooking steak surrounded by layers of chuck that require hours of braising or a trip to the grinder.

Despite its name, the Denver steak did not originate in Colorado; the moniker was selected by focus group participants when the Beef Checkoff Program (of the famous “Beef: It’s What’s for Dinner” campaign) rolled out some shiny new cuts to tempt consumers.

When in doubt: Marinate, then grill.

Filet

Even if you grew up under a vegan rock, you’re probably familiar with filet mignon. This is considered the Rolls Royce of beef cuts, and is the most expensive part of the cow. Mignon, in French, translates to “small and cute,” or delicate.

Also called the tenderloin, this small muscle rests on the inside of the spine on the lower back and barely moves. This popular cut has inspired countless recipes, including classic preparations like wrapping it in bacon, smothering it in Bordelaise or Béarnaise, or baking it in dough à la beef Wellington.

When in doubt: Sear in a hot pan, followed by an oven roasting. But be sure sure not to overcook; the lower fat content makes it easy to dry out.

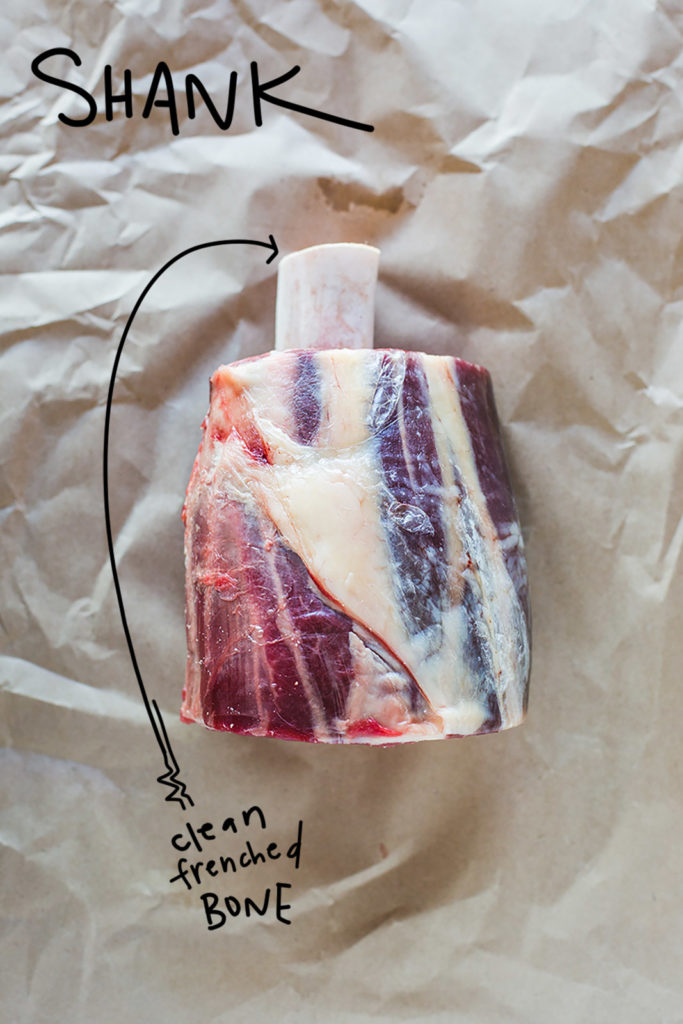

Shank

Cuts with clean, frenched bones are very attractive to customers who can present an impressive table-side feast to their guests. Standing uses only the hind shank for this cut (the fore shank is deboned and thrown into sausage mix), which has a round bone with lots of lovely, rich marrow. Unlike a bone in a quick-cooking cut that doesn’t have enough time to release its flavor, when cooked for hours the bone and marrow add complexity and depth. In similar preparations, this wins out over cooking something like chuck roast.

Standing explains his suggested cooking method. “The most accessible thing for everybody is a covered Dutch oven or pot,” he says. “Get a bunch of veggies nice and browned, [add] some stock like beef or chicken, some red wine or some dark beer in the mix, and just forget about it.”

When in doubt: Braise low and slow—or smoke it.

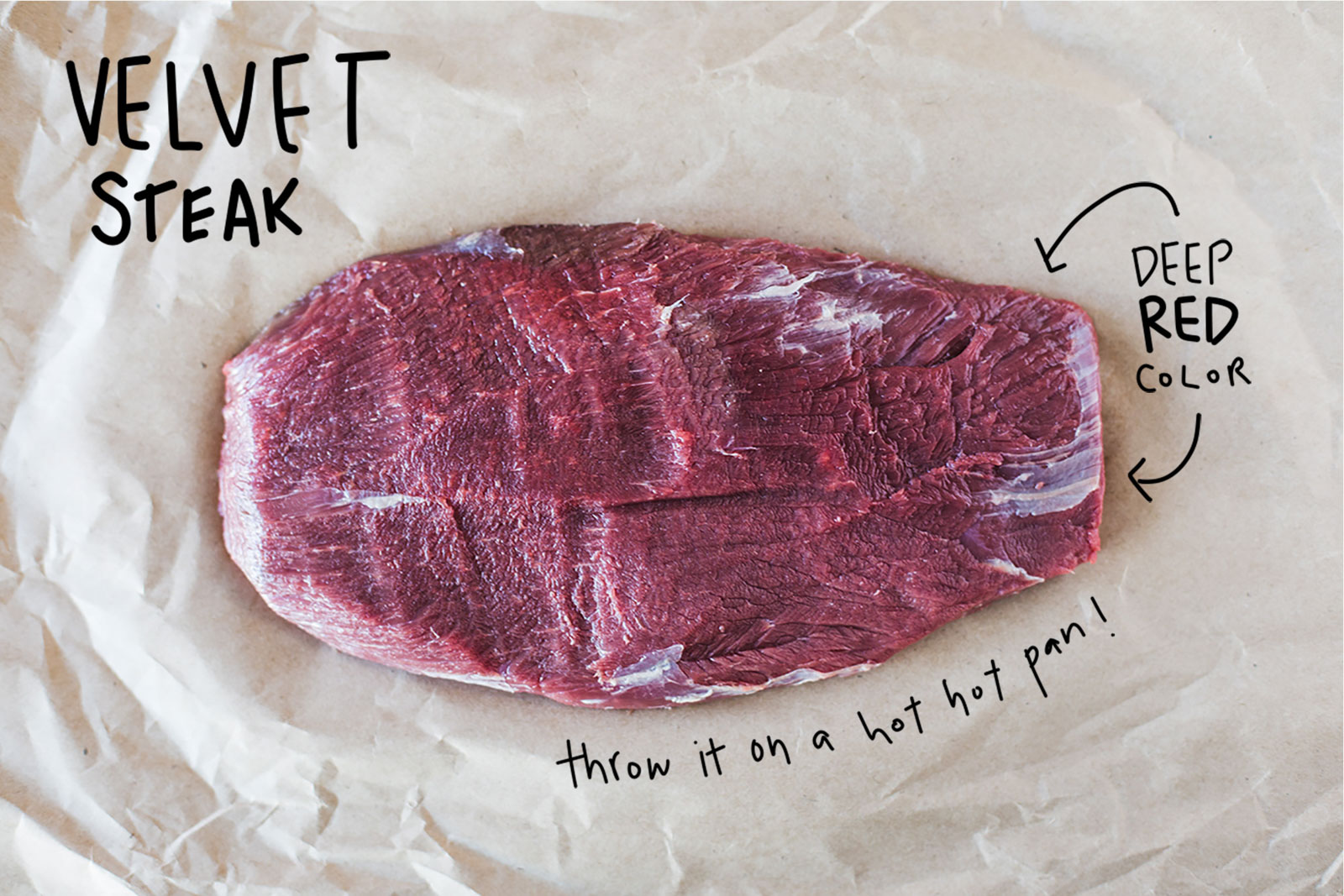

Velvet Steak

The velvet steak, also known as “the merlot,” sits in an area known as the heel in the calf muscle. It has a slightly more rich, red color than the meat around it and a fine grain. It appears fairly thin, but puffs up when it hits the heat. Standing recommends just a quick sear though; this one is for those who prefer their steaks bloody. He even suggests the velvet as a contender for tartare; it’s very low in fat and extremely juicy.

For the butcher, this specialty cut requires a lot of effort to extract and knowledge of its whereabouts. To demonstrate, Standing pulls out a hind quarter and begins excavating. By the time he finally separates the oval-shaped muscle, he’s surrounded by scattered subprimals, hunks of meat, and bones. He surveys his butcher block.

“Working in the grocery, [the heel] is just hamburger; you throw the whole thing in the grinder,” Standing says.“Then I discovered this fancy little thing.”

When in doubt: Throw it on a super hot pan, or cube it raw for tartare.

Picanha

This steak comes with its own basting liquid. Normally a steak gets better with a gentle showering of melted butter, and while that still applies here, the picanha comes pre-equipped with a stripe of ready-to-render fat.

Less likely to crop up at large retailers in the United States, the picanha is extremely popular at churrascarias in Brazil. Also called culotte in France, which is an evolution of the word calotte—a type of skull cap worn by Roman catholic priests. The cut comes from the top sirloin cap located in the rump near the tailbone.

“We have awesome customers who are open-minded and don’t come in looking for one specific thing; they just want to see what we have,” Standing adds after a customer exits, picanha in hand. “Picanha is the one thing that stands out to everybody—they don’t know how to [pronounce] it.” (It’s pronounced pea-ka-nya.)

When in doubt: Slap it on a hot pan. Or if you’re feeling adventurous, do as the Brazilians do—horseshoe skewer it over an open fire, churrasco-style.

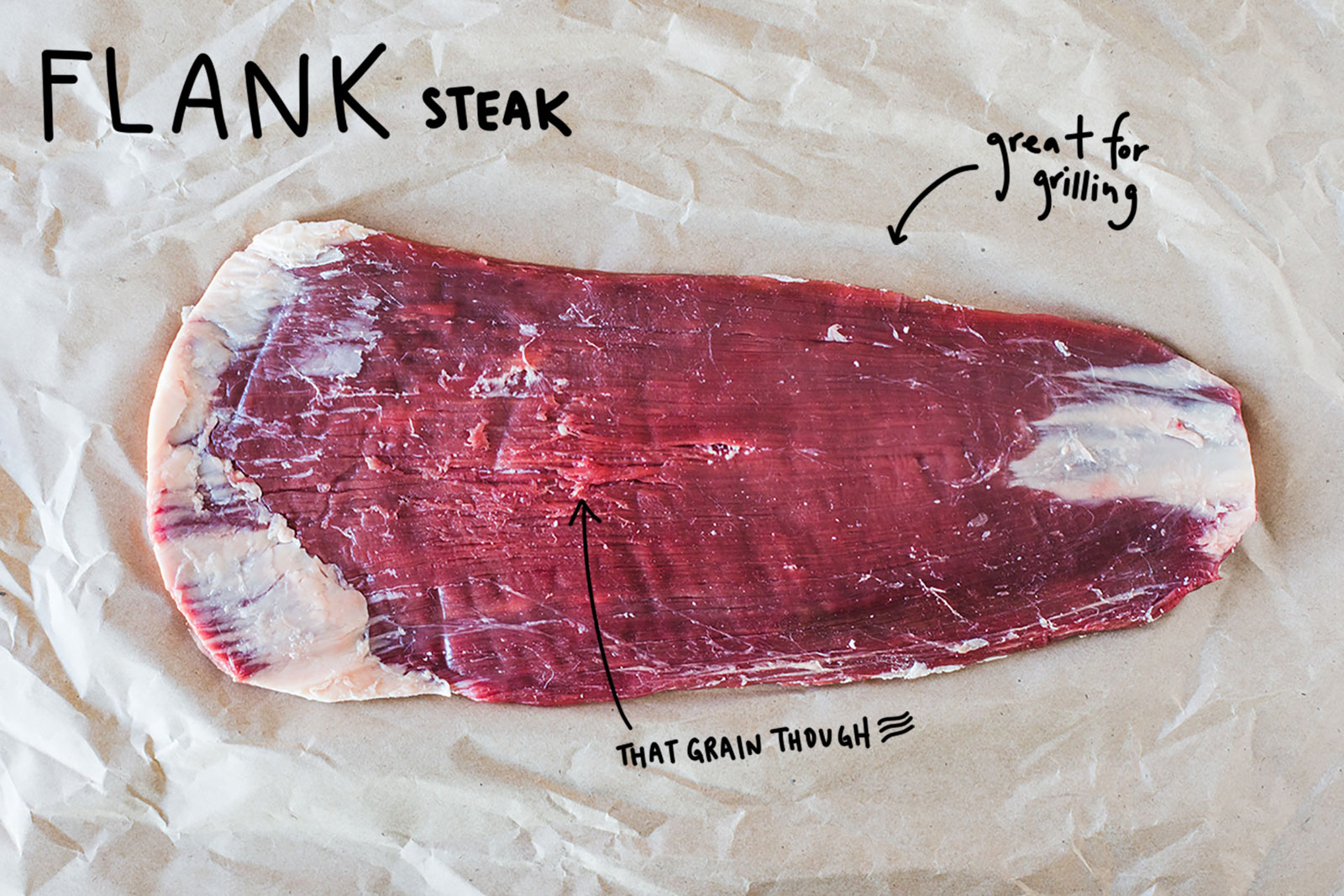

Flank Steak

Flank steak is great for grilling, takes to marinades and sauces well, and has a slightly firmer texture than something like the flat-iron. It comes from the lower abdominal area—near the hip flexor—and sports a long, visible grain.

“I always hesitate to say it’s tougher because it definitely has that kind of a bite; but if you slice it against that grain, it’s really tender,” Standing explains. “If you think about if you have a bunch of rubber bands [stretched out lengthwise] and you slice across them, it’ll just fall apart in little pieces.”

When in doubt: Grill and top with chimichurri, or stir fry.

Bone-in Neck

To support a heavy, grazing head, the steer’s neck works non-stop all day long. This strong muscle needs all the softening it can get, and tastes best after a long, slow braise. Additionally, leaving in the large spine bone improves flavor and complexity. Standing suggests heavily browning all sides of the meat that aren’t exposed bone before adding liquid and aromatics. He also prefers the neck for pot roast as opposed to the traditional chuck meat.

“The chuck roast has lots of different muscles and they all act differently [when cooked], which is why we break it up,” Standing says. “The neck, on the other hand, is all kind of the same [type of muscle] that all does well at the same temperature, with the same cook time.”

When in doubt: Braise away for many hours; it’s a good contender for the Crockpot.

Oxtail

Between each vertebrae of the tail lies collagen-rich cartilage that reduces and turns any stock into liquid gold. The throat-coating fat, paired with highly flavorful meat from a long braise makes this a popular option for any adventurous, patient cook. “All that collagen gelatinizes in there and you can reduce that down to where that broth is going to be a solid when it’s cooled, like meat Jell-O,” remarks Standing. “So much flavor.”

The unique qualities of this cut come at a cost, however. With only one tail per steer, demand may outstrip supply. For Standing, that’s a good thing. In the broader grocery market, customers are often accustomed to getting what they want, whenever they want, and that model is unsustainable. Prizing certain cuts over others forces farmers to overproduce so they might meet the desire for that small, but valuable portion. He’s combatting the wasteful habit through practice and education. When people walk through his door asking for a certain item that’s sold out, it’s an opportunity to explain why, offer alternatives, or turn customers on to something completely new they may not have cooked before.

When in doubt: Give it a long, slow braise.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.