March 1, 2022

Decolonizing Maple Syrup

The fact that maple syrup is so rarely acknowledged as an Indigenous invention is a direct result of centuries of colonization and the concerted effort to erase Native culture and identity.

Maple syrup has long enjoyed an easy ubiquity on breakfast tables and shelves of souvenir shops all over North America. Gallon for gallon, it is more expensive than crude oil, and historically, it is centuries, if not millennia, older. But conversations around maple syrup rarely exceed the technical depth of grading and purity, the infamy of the supposed maple syrup mafia, or the racially charged branding of Aunt Jemima. Excluded entirely from these discussions is its true origin as an ingenious invention, simultaneously food and medicine, of the Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee and Wabanaki peoples of northeastern North America, also known as Turtle Island.

The true origins of maple syrup are couched in legends—of a boy, exhausted from practicing his hunting skills, falling asleep with his tomahawk wedged in a sugar maple. Of maple syrup running freely from trees until Nanabozho, an Ojibwe trickster figure and culture hero, filled the trees with water, turning the syrup into a sap that required processing to prevent his people from becoming indolent. Of a woman—in some cases an Algonquin chief’s wife, and in others, a daughter or granddaughter—mistaking maple sap for water and boiling meat in it, creating a delicious surprise. Or of observing squirrels or woodpeckers drinking beads of sap from incisions in the trees’ bark.

By some accounts, Indigenous peoples like the Akwesasne Mohawks have been using maple sap, sugar and syrup to flavor and preserve meat for roughly 9,000 years. Maple products have long been revered in many First Nations communities as both energy boosting and for their medicinal and anesthetic properties, believed by some to be a natural remedy to cleanse the kidneys, liver or digestive tract.

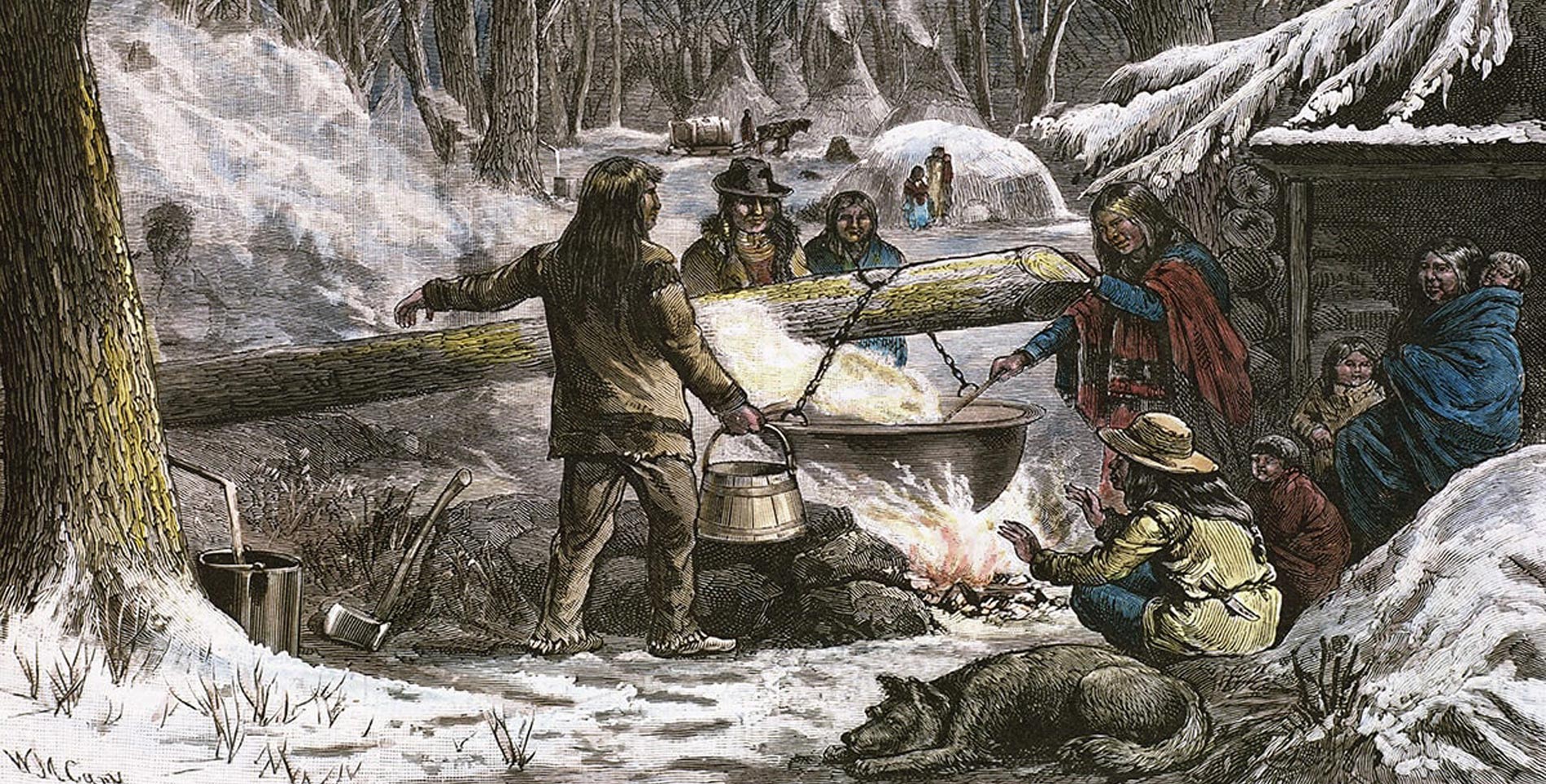

As the maple harvest coincides with the end of a long winter and the promise of spring, historically, it has held special significance in many First Nations communities, such as the Ojibwe and Haudenosaunee, as an opportunity for ceremony and celebration. While these differ from nation to nation, they may include sacred dances, offerings of tobacco to maple trees as a form of giving thanks, maple sugar festivals, and community socials. Some elders recount that the first loaf of maple sugar produced from the harvest was traditionally offered in the middle of a lake to thank the water and the tree for their gifts. While these rituals are maintained to a certain extent in some communities even today, they feel entirely divorced from the plastic and glass jugs of syrup lining the breakfast aisles of big-box stores across North America.

The disconnect between Indigenous knowledge and modern perceptions of maple products is entirely by design. Traditional First Nations and Métis influence on maple syrup production is almost never acknowledged by non-Indigenous maple companies, with images of lumberjacks, idyllic snow-covered maple groves known as sugarbushes, and one very problematic Aunt Jemima being used to market the product as a quaint colonial tradition, part of an all-American or classic Canadian breakfast. That isn’t to say this imagery should be replaced by stereotypical or damaging representations of First Nations people à la Land O’Lakes butter or Indian Head cornmeal, but rather to question why maple products are never advertised as millennia-old traditional foods with both taste and health benefits, the way Ayurveda is revered as ancient wisdom or how even paleo diets hinge on an apparent nostalgia for 10,000 years ago.

Centuries of colonization on Turtle Island have separated many First Nations communities from their traditional maple harvests with many losing their sugarbushes due to forced relocations to reservations and large-scale clear cutting. Government policies, like Canada’s Indian Act, served to further this agenda by banning cultural ceremonies and practices from 1884 until 1951, forcing those able to continue harvesting maple sap to either eliminate the ceremonial and spiritual aspects of it or to maintain them in secret and at significant personal risk. The Indian Act also introduced the Indian residential school system, designed expressly to “kill the Indian in the child,” dismantling Indigenous knowledge and culture through forced assimilation and abuse. The full impact of those schools, the last of which closed in 1996 in Canada, is still unknown, as unmarked graves on those schools’ grounds, containing bodies of children as young as three years old, continue to be discovered, and testimonies from survivors recounting their trauma come to light.

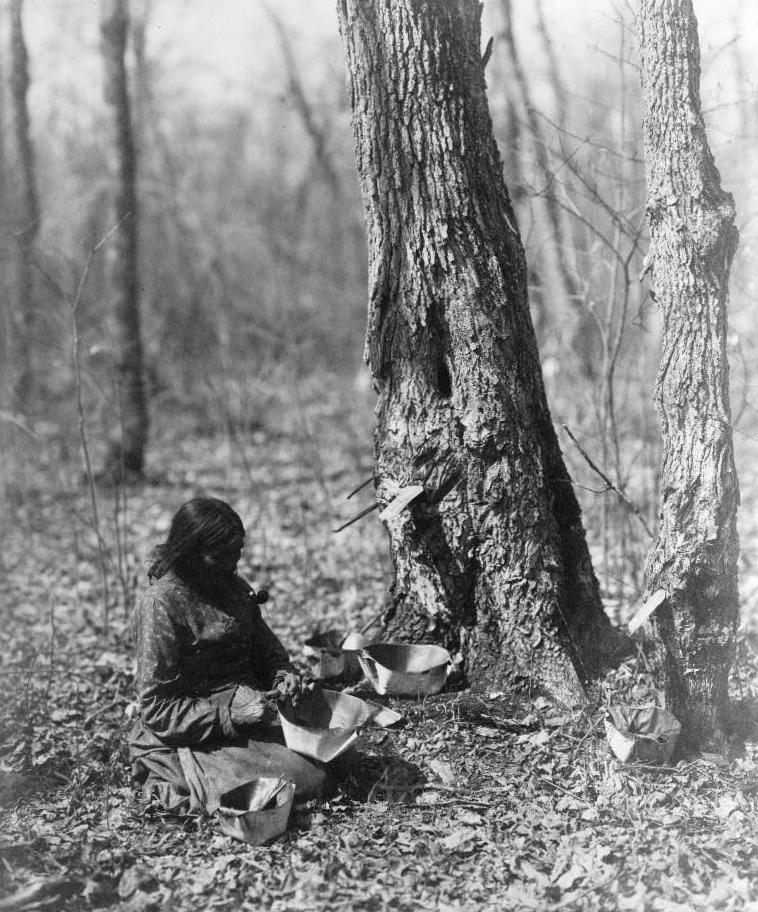

By that point, however, the First Nations people of northeastern North America already freely shared with French and English colonizers the secrets of how to tap sugar maples for an abundant late-winter source of subsistence, and the production of maple syrup had seen its own form of industrialization. The demand for maple products, not only within North America but also in Europe, had grown considerably. In many places, the buckets traditionally used to collect sap were replaced by tubing systems, and shallow evaporators were introduced to reduce processing time. Traditional wisdom—like heating the sap over a fire made of maple logs to create an even better taste, or letting the sap sit overnight in a bucket so much of the water would rise to the top and freeze, leaving a more concentrated maple sugar at the bottom, or storing it in makaks (birch bark boxes sewn tight with spruce root)—was mostly forgotten.

But a reclamation of sorts has begun, with Indigenous-owned businesses producing and selling their own maple syrup with an artisanal quality to it and broader visions to uplift their communities. Deborah Aaron, co-founder of Giizhigat Maple Products in Northern Ontario, shares a perspective on maple syrup that is filled with spirituality and gratitude.

“Spirit came and shared with us today that maple syrup is ‘the sweet medicine of loving life,’” she explains.

Aaron and her husband, Isaac Day, an Elder and Knowledge Keeper from the Serpent River First Nation in Northern Ontario, founded Giizhigat to support his life-long goal to start a teaching lodge and healing center where all people could come together to learn and grow. Day recalls the happy memories and peacefulness of the maple harvest as a child; families would build spruce huts, hunt and fish during the day to feed everyone, and elders would sit around the fire and boil the sap all night, telling stories, while the children would fall asleep listening to them. Now, they hope to recreate that opportunity for others.

“One of our goals is to have a traditional maple syrup camp on our farm. To gather and share stories,” Aaron says.

This sentiment of community and togetherness in boiling maple sap is echoed by Marie Harnois, Operations Manager at Passamaquoddy Maple, located in Maine and owned by the Passamaquoddy Tribe. She fondly recounts their record of preparing an impressive 700 gallons of maple syrup within a sleepless 24-hour period during one maple harvesting season, and speaks passionately about the broader cultural significance of their “tree-to-table company,” as she calls it.

“To take a traditional Indigenous product and bring it to market, we take a lot of pride in that,” Harnois shares. “Our peoples’ name is on it. It’s a point of pride for the people on our reservation and others off the reservation as well.”

Apart from the pride she takes in Passamaquoddy’s products, her enthusiasm and deep knowledge are also evident as she thoroughly explains their complex production process, which involves thousands of taps, stainless steel tanks, double filtration, hand-bottling, and a mission to “make it sparkle,” as Harnois describes it.

Although maple syrup is a millennia-old Indigenous tradition, both Aaron and Harnois recount that setting up these businesses was no walk in the sugarbush. “The maple syrup business is not cheap to get into—the modern equipment and tubing needed is expensive—so the capital investment required to get into the maple syrup business with modern technology has been one of our biggest challenges as a small business,” Harnois explains.

For Passamaquoddy Maple, in spite of owning more than 65,000 acres of land with plenty of Mahgan (sugar maple trees), it took years to secure the funding to tap into this natural resource and eventually bring the product to market. Now, they boast an 80% customer return rate, have created employment opportunities for the community, and are expanding into new markets.

Wabanaki Maple, another Indigenous-owned maple syrup brand, offers a barrel-aged bourbon maple syrup with 2% alcohol content, a far cry from the common table syrups on the market. Located on Neqotkuk in present day New Brunswick, Wabanaki Maple is 100% Indigenous female-owned, a poetic ode to a time when sugarbushes were passed down matrilineally, per some Indigenous traditions.

So deeply embedded in Indigenous traditions is maple syrup, that Honor the Earth, an Indigenous organization of water protectors, also sells a creatively branded “Pancakes Not Pipelines” Ojibwe maple syrup to support their fundraising efforts. Theirs is a wood-boiled, horse-hauled maple syrup, described as “a treat enjoyed by our Anishnaabeg ancestors for generations,” with proceeds going toward protecting sacred lands and supporting frontline Native communities in the fight against environmental degradation.

What is the legacy of maple syrup if not a legacy of uncredited Indigenous ingenuity, a tradition that has endured cultural genocides and centuries of appropriation? As conversations around reconciliation happen, maple syrup can no longer remain a symbol of North American settler-colonial identity. Over thousands of years, it has nourished generations of First Nations people through the ends of winter as stores of food dwindled. It is so much more than a topping for flapjacks or waffles. As Giizhigat’s slogan goes, it is “adding more love and sweetness to our lives.” It is a gift from nature, and from the Indigenous communities who have shared it with the world.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.