Editor’s note: This story is published in The What We Carry Issue of Life & Thyme Post, our exclusive newspaper for Life & Thyme members. Get your copy.

On Edisto Island, just an hour drive from Charleston, South Carolina, Emily Meggett is a celebrity. There isn’t a market or community center in town that isn’t aware of the 89-year-old local. Her all-star status is well deserved: at almost 90 years old, Emily Meggett, a Gullah Geechee chef and homecook, has preserved the history and educated the world about the culinary landscape of Lowcountry and Gullah Geechee cooking.

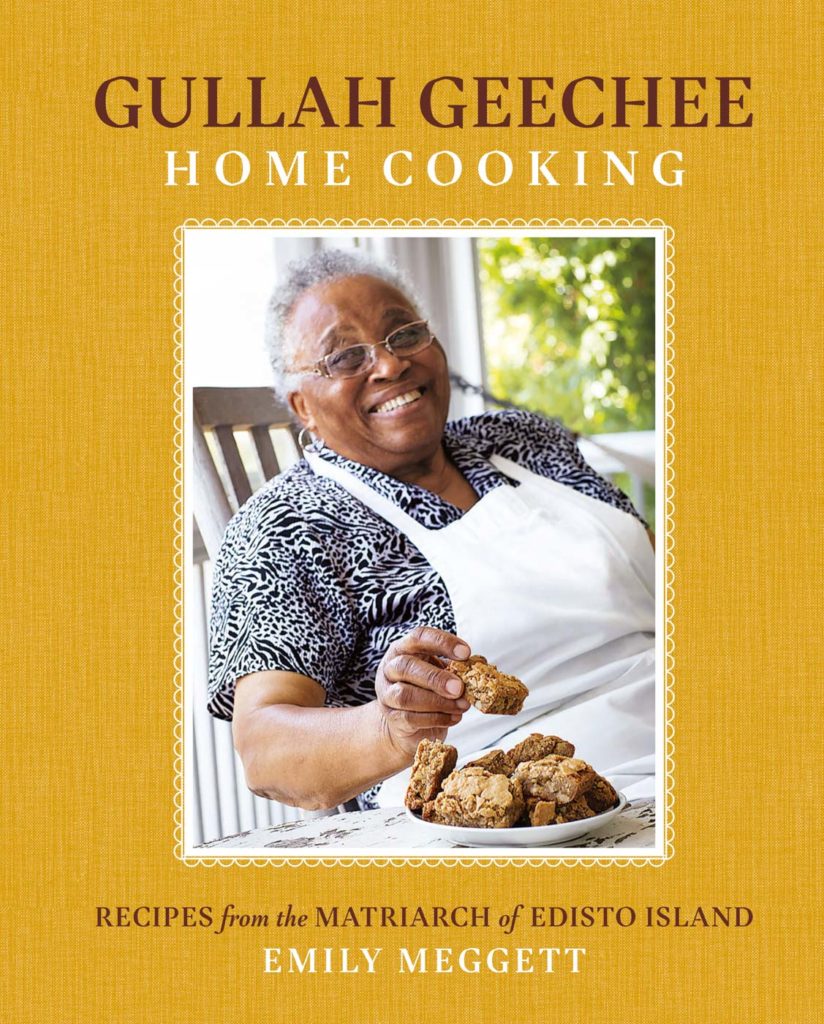

Her debut cookbook, Gullah Geechee Home Cooking: Recipes from the Matriarch of Edisto Island, shares invaluable information about the Gullah Geechee people. Descendants of African American enslaved people, the Gullah Geechee people are a group of Black Americans who preserved many African traditions, and created their own culture, language and foodways along the Southerneastern coast of the United States in South Carolina, Georgia and upper Florida.

Meggett’s book shares quintessential recipes in Gullah Geechee cuisine, such as the tomato-laden red rice, comforting chicken perloo, and irresistible chewies, a cousin of blondies. Meggett’s cuisine has become symbolic of a culture that was historically vilified and sometimes completely ignored (it wasn’t until Miss Emily was an older child that she learned what “Gullah Geechee” meant, and its role in her heritage and life), but that has undoubtedly served as the foundation of Southern food and American cuisine.

Miss Emily, who’s never used a cookbook, but authored one with myself and oral historian Trelani Michelle, is eager to share her expertise about good Gullah Geechee home-cooking and the importance of enjoying good food—and knowing where it comes from.

What was the first meal that you prepared with “mama” (Elizabeth Major Hutchinson)?

Grits and gravy. [As we made it more], it could be shrimp or fish. That would be your main meal.

What do you remember about the meals you ate as a child?

I remember salt pork with wild cat sauce. They would kill the cow and the pig, and then they would slice off the fat. They’d fry that. And then mama would say, “Go outside and bring me some onions.” She had her garden right by her kitchen window. I’d get the green scallions and onions, pour some grease off that pork, and put some flour in that, and then I’d make that sauce. And once I’d make that sauce, if it wasn’t brown enough, [mama] would take coffee and add some color and make a gravy. That’s a meal. You put it on grits and you put it on rice.

You would think that we were poor back then, but we were rich. Because you know what? We had everything that we needed. Fish, shrimp, crab, oysters. My uncle would go to the creek, and whatever he brought back? That’s what we would eat. We ate from the creek to the garden. We ate poultry, fish, shrimp, crab, oysters, corn, beans.

Everybody here on the island eats from the garden. You didn’t have to go to the store, except for a few things—except sugar—because we had everything we needed here. We had our own rice pond, okra, beans, butter beans, crowder peas—we had everything.

You talk a lot about the importance of fresh meat, seafood and produce. What were some of the things that were available to you and your family when you were growing up? How has that changed?

A lot of things have changed from then. Nobody has a garden now. Nobody has cows, pigs, a yard full of chickens, duck, turkey, guinea. Nobody here on this island that I know, maybe except one or two people, has that anymore. But when I was growing up, we had all of those things.

Mama had about 200 heads of chicken; there were so many that you didn’t have walking space in the yard. The only things mama had to go to the store for were things like sugar and salt, and oil and pepper. We didn’t have to go to the store for rice because we had our own rice pond. And we had corn, sugar, millet, sugar cane, and all of those things went to the mill. They were processed and brought back, and we had what we needed.

When do you remember first hearing the phrase “Gullah Geechee,” and what did you think it meant?

Here on Edisto, everybody was saying, “Edisto Island ain’t nothin’ but Geechee. Gullah Geechee girls and Gullah Geechee boys.” As I grew up, they said Gullah Geechee are country girls and country boys. “They’re all Gullah Geechee because they live on the island.” And there wasn’t a way for us to get off the island except to catch the ferry, because there weren’t a whole lot of cars here.

So we were in the country, and we were the Gullah Geechee girls. The way we speak and the language we use—the city boys and city girls didn’t use that kind of a language. And that comes from way, way back. Edisto will always be Geechee.

What are some of the things that Gullah Geechee people eat?

They eat everything. It’s things like red rice, chicken, seafood, Hoppin’ John. Everything.

Why is your Gullah Geechee heritage so important to your cooking?

Because I love cooking. And I love to see all the people cook, and I like to show what I learned. If someone wants to know how I fix a pork roast or ham or turkey, I like to show them how I do it—and how we do it.

What’s your favorite Gullah Geechee dish?

All of my dishes are my favorite because that’s how I learned. [Laughter] The way that I fix it, I like it, and I hope other people like it too.

You talk a lot about the importance of family. How does cooking allow you to carry the stories and history of your family?

Everybody wants to learn to do it “how grammy does it,” so I know what I’m doing is important. They [my family] call me and ask me to show them how to do it. And so future generations learn how to do these things, and that continues the story and the lessons.

What do you want people to take away from your cookbook?

All I want them to do is to try the recipes in the book, and enjoy it. That’s all that matters to me.

Photos courtesy of Clay Williams

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.