Early on, after working at a grocery store, Jered Standing stopped eating meat. The more he learned about the negative impact of conventional meat products—a high environmental toll, human health concerns, and animal welfare—the less he liked his job slinging brisket. Fortunately for us, he found his way back to the meat counter. Standing explains, “all the exact same ethical reasons I wasn’t eating meat or dairy led me back to [butchery], because I realized that not eating meat doesn’t actually put any pressure on the industry to change.” Rather than quitting meat cold-turkey, he prefers supporting the farmers and businesses working toward sustainability, and luring enough meat eaters away from conventionally raised animals forces the competition to take notice. “I wanted to work in the industry to make it better,” he says.

For his pork, Standing is quick to point out that pasture-raising pigs looks different to the outside observer than pasture-raised steer. Pigs still need pens of some sort or they will destroy a pasture by digging and nesting. The trick to finding an ethically raised product is visiting the farm itself, and since most shoppers don’t have the time or access to do this themselves, Standing does it for them by meeting with every one of his suppliers.

Healthy, contented pigs still need lots of room to run, to roll in the mud and root around for additional nutrients. Standing gets his pigs from Devil’s Gulch Ranch, a farm in Northern California at the end of “a scary windy road on the edge of a cliff that goes down into the canyon.” But that doesn’t seem to sour the residents’ mood. According to Standing, “it’s all wooded, lots of oak trees and—most importantly—happy pigs.” The pigs are a crossed heritage breed—a mix of Yorkshire and Duroc or Berkshire. They’re fed whey from nearby dairy farms, spent grains from local breweries, and have ample opportunity to scavenge for tubers and acorns to supplement their diet.

When buying pork, Standing says he looks for a “darker red meat, good marbling, and reasonable fat cover.” He says the breed he stocks is much fattier than the average grocery store pork.

Probably the most versatile animal to cook, pigs have the most usable parts and a vast library of preparation methods, from sausage and salami making to slow cooking and barbecue. Pork is a staple for many cultures, the backbone of dishes like Mexican cohinita pibil, Japanese tonkatsu, Indian vindaloo, Cantonese char sui, British black pudding, and the sliced ham centerpiece of many Christmas tables.

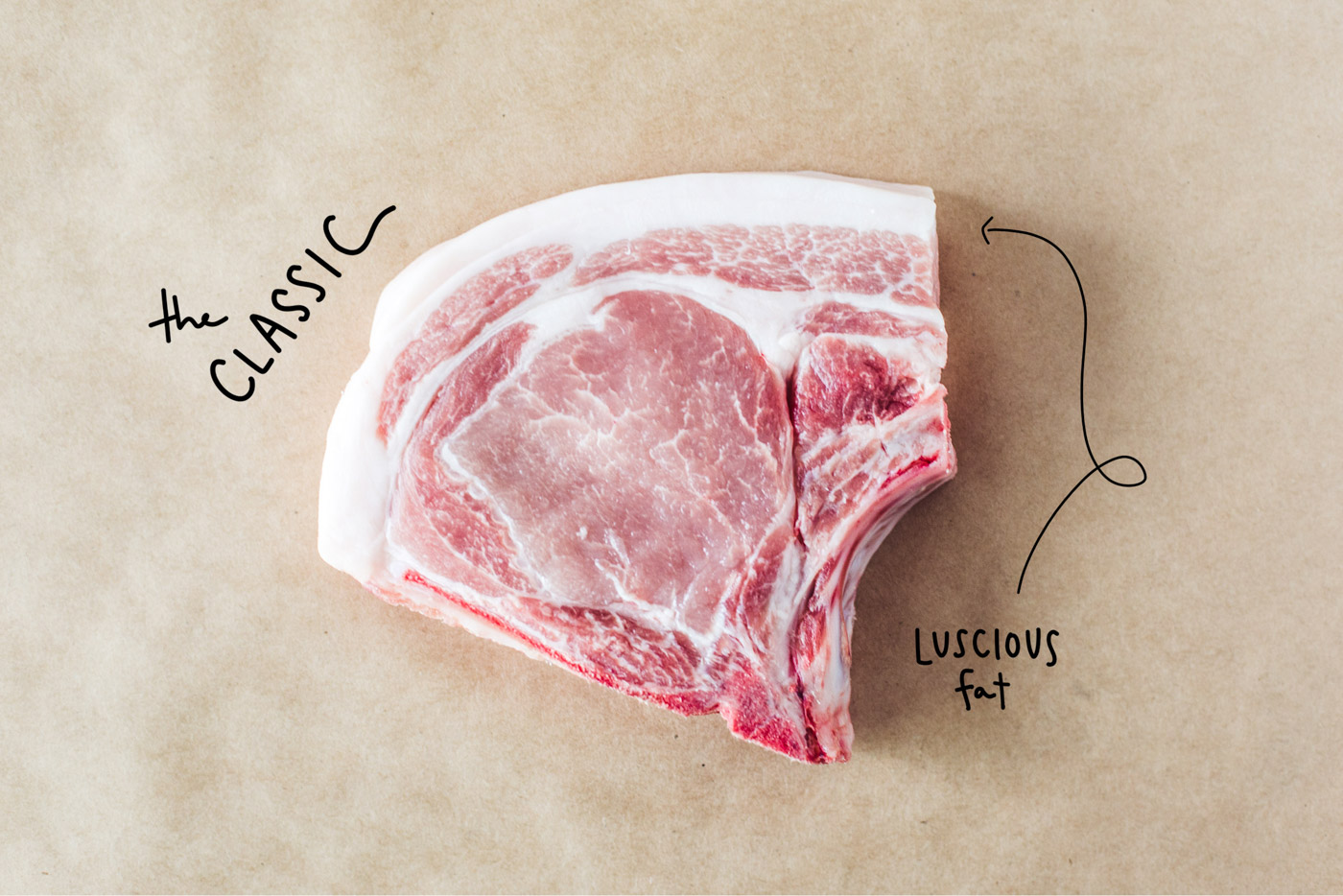

Rib Chop

The pork equivalent of the beef ribeye, the rib chop is what we know as the classic pork chop. This is the most popular cut, with plenty of luscious fat. Standing cuts his considerably thicker than most, providing cross sections over an inch wide. “People are still in the mindset that you need to cook the hell out of pork,” he explains. “[They] think you have to cook it like it’s chicken, going all the way up to 165 [degrees]. If I cut it thicker, it’s more likely you’re not going to overdo it.”

When in doubt: Lightly salt and cook in a cast iron pan on very high heat, until it reaches an interior temperature of around 140 degrees Fahrenheit. While many people brine their pork chops, Standing recommends skipping that step, letting the meat shine. “I like the sweetness of the fat when it’s not covered up with a bunch of salt and other flavors,” he says.

Butt

Despite it’s perplexing name, pork butt, or Boston butt, is from the upper shoulder region and not the rump of the animal. The name comes from the large barrels, or butts, used to transport New England pork in pre-Revolutionary and Revolutionary times.

This crowd pleaser (and crowd feeder, with the average butt weighing in at eight to ten pounds) is also one of the more forgiving cuts. As Standing details, “it is the most user-friendly, especially if you are new to smoking or braising.” He explains that even if it becomes overcooked, simply redistributing some of the fat by hand will help return moisture to the meat. He continues, “If you [weren’t able to cook it long enough] to where it was shredding—if that’s what you’re going for—it would still slice and eat just fine.”

When in doubt: Cook low and slow, for many hours. This cut is traditionally the go-to for pulled pork and carnitas.

Coppa

One muscle within the Boston butt tends to dry out with the low and slow method of cooking, so Standing chooses to remove that piece and sell it as his favorite cut: the coppa.

Coppa is made up of one long fatty muscle that starts in the neck and shoulder and runs into the rib bones along the back. The same muscle comprises part of the rib chops. Standing is usually only able to pull two or three coppa steaks from the animal.

Cured coppa, also known as capocollo in Italy, is one of the few whole muscle salumi, alongside other entire cut cures like prosciutto, bacon and lardo. Because of its wonderful curing potential, this cut is one of the most highly prized in Italy, although often overlooked elsewhere.

When in doubt: Throw it in the cast iron pan. There’s a good amount of fat marbling, so this cut might cause too many flare-ups on the grill. If you’re really ambitious, give curing a go.

Belly

Boy, do people love bacon. There are bacon contests, articles comparing the merits of various bacon thicknesses, debates over what the word bacon even means (see Canadian and British, which are made from the back or loin), and memes about Ron Swanson’s devotion to the grease strips (“I can’t think of anything more noble to go to war over, than bacon and eggs”). Cured, pork belly swiftly ascends to the throne of the meat kingdom. Pigs have an abdomen structure unlike any other animal we eat regularly, standing out for its thick layers of fat (lending to the belly’s covetous place in the food loving world).

Standing recommends many preparations for pork belly, but suggests that bacon is a fun home project for the curing novice. “It’s really easy for me to give somebody a very simple curing recipe with things they already have,” he says. Standing says with just “salt, sugar, and a Ziplock bag, the belly can be left in the refrigerator and flipped every day for five to seven days, depending on the size of the belly. If you can smoke it, that’s awesome. If you can’t, do a low heat oven roast just to par cook it. Then you feel like a magician because you’ve made bacon.” Look for belly sold with the skin on, which helps prevent over-salting and is sturdier to hook into for smoking.

When in doubt: Cook chunks of belly low and slow for a melt-in-your-mouth texture. Or, try your hand at curing to impress your bacon-loving friends.

Feet

Feet, trotters, or pettitoes look somewhat grisly, and cloven hooves are an oft-referenced characteristic for off-limits animals in Jewish and Muslim cultures. Pigs’ feet contain a high percentage of cartilage and collagen, making them ideal for long-cooking preparations, like braising with sauces and spices for a rich pork stew or simmering into into soup. Popular in Asian cooking, those same qualities are crucial for viscous, throat-coating ramen broth, and are the reason your leftovers are solid the next day (at 160 degrees Fahrenheit the protein bonds begin to unravel and the gelatin causes the liquid to thicken). As a help to the home cook, Standing offers to split the feet to access the connective tissue quickly and efficiently.

When in doubt: Simmer a big pot of stock, or attempt to make Fergus Henderson’s trotter gear (a dish Standing likens to “a jar of really fun jelly.”)

Sirloin Chops

From a harder working muscle, the sirloin chop—also known as rump steak—has a darker color compared to the pale pink of its next door neighbor the loin chop. That deep red usually indicates a higher concentration of the protein myoglobin and a bouquet of nutrients that contribute to a more robust flavor. Don’t try to fool your kosher friends with this one; its taste is distinctly porky. Baked, roasted, marinated or glazed, there’s no shortage of sirloin chop recipes.

When in doubt: Sear in a hot cast iron pan, using the rendered fat collected in the pan to baste.

Jowl

Not to be confused with pork cheek—which sits above the cheekbone and is great for braising—the jowl is from the outer face and chin of the pig, in a lower neck region. “Pigs are pretending to have a neck, let’s put it that way,” jokes Standing. With its ribboned layers of pink muscle and white fat, the jowl resembles a smaller pork belly and can be prepared similarly, but has a more delicate fat that renders at a low temperature. It’s commonly cured with salt, sugar and spices, a quick method that results in delicious salt pork to flavor dishes of beans or greens. Longer cures like jowl bacon and Guanciale are fantastic on their own, and are often used in pasta sauces.

As for the rest of the head, Standing dries the snout and ears for canine friends, and anything left goes into pork stock.

When in doubt: Cube and use in sausage, or do a quick home cure for salt pork.

Ground

Unlike other meat grinds, ground pork has a higher fat content and is therefore perfect for sturdy sauces, complex sausages, and superior meatballs. Standing opines, “If you have any recipe that [calls for] ground chicken or turkey, just get ground pork. [There are] probably a million reasons people don’t want to take that advice, but I can’t think of a recipe that isn’t going to work with it.” Ground beef also benefits from the addition of some ground pork—the combination makes a juicier burger and helps sausage mixes bind without the need for eggs or breadcrumbs.

When in doubt: Ground pork is the perfect playground for a novice cook. Beyond making a simple burger, Standing suggests trying homemade sausage. “Even if you don’t want to put it in a casing, make a loose sausage you can use on pizza, or make patties out of it.” Standing says sausage making is fun and forgiving. He says, “As long as you get a proper salt percentage, you can add any flavors that you want.”

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.