HOW IMMIGRATION AND TRADE POLICY HAVE SHAPED U.S. AGRICULTURE

A history of immigration, trade and discriminatory economic policies have made U.S. farms dependent on exploitable labor mostly by Latinx immigrants.

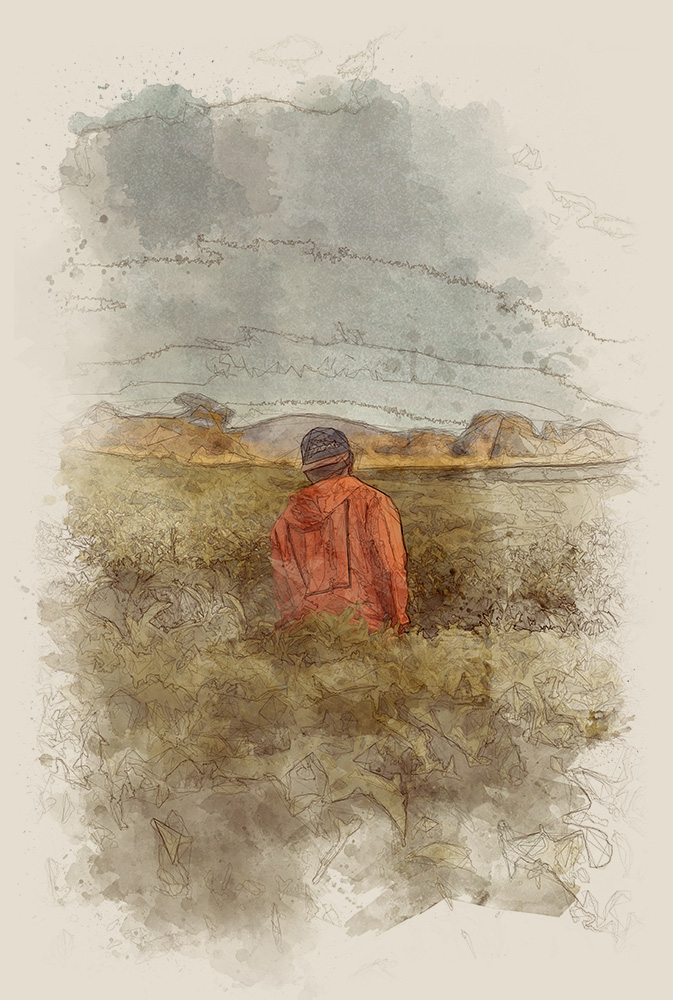

In a field in Las Lomas, California, Bertha Magaña pulled strawberries from their stems, a quick movement she’s repeated thousands of times. Magaña was fifteen years old when her family came from Mexico to California to work in the strawberry fields. “It was very hard, but it was the work that we had,” she says as the coastal fog creeps in toward the stalks of blue and white corn behind her. But after a lifetime of harvesting other people’s crops, Magaña is a permanent U.S. resident and owns a piece of California’s strawberry heartland. She purchased nine acres in 2015, converting the property into an organic farm that sells produce to a local broker. “We thought it was impossible, but here we are,” she says.

Magaña is an exception amongst farm owners in the U.S., ninety-eight percent of whom are white due to a legacy left by government sponsored land theft, violence, and discriminatory policies that have persistently stripped land from people of color.

Increasing land costs and access to financial information and resources are additional barriers for people of color to establish their own farms. Finding a commercial lender to purchase land is generally difficult for aspiring farmers, and Magaña only had the opportunity to buy her property in the first place through a rental agreement clause giving her first right of refusal when her landlord wanted to sell. That agreement and her USDA loan were secured with assistance from California FarmLink, an organization that attempts to level the playing field by linking independent farmers and ranchers with access to land and capital.

“Both of those things tend to be huge obstacles for farmers in general, and even more so for first generation farmers and for immigrants that don’t have the social networks and the experience working within the financial system,” says Brett Melone, director of lending for California FarmLink. He adds that documentation status also presents barriers to acquiring land.

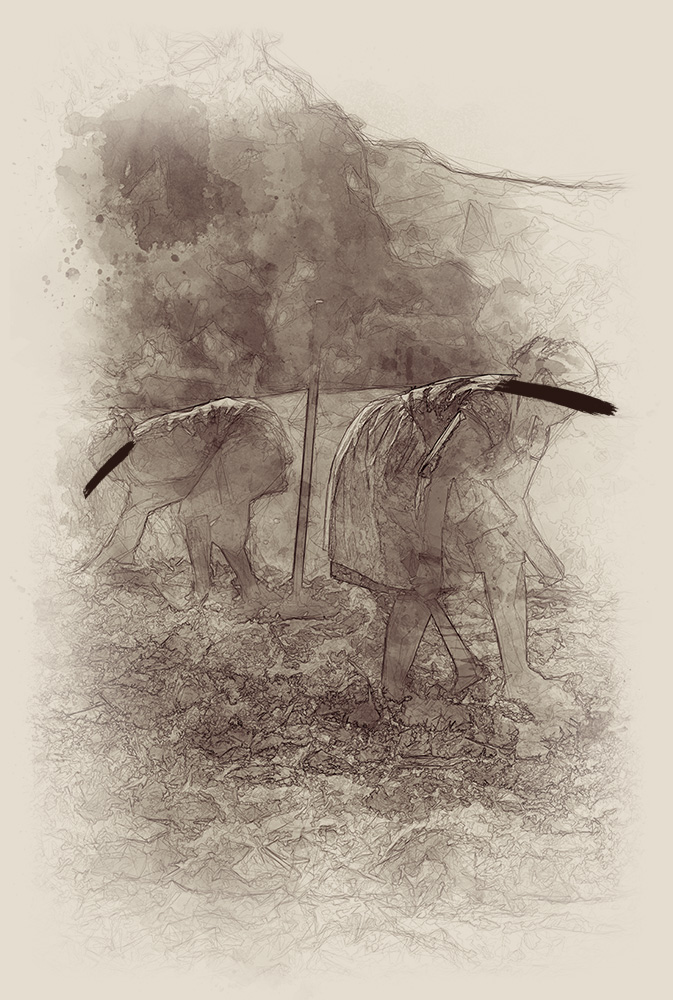

While mostly sidelined from ownership, it’s no secret that America’s $132 billion agricultural sector relies on families like Magaña’s, Latinx immigrants who make up about seventy percent of the farming workforce. Most of the country’s 2.5 million farmworkers are of Mexican descent, and at least half are undocumented. Wages are generally low; in 2019 farmworkers earned less than what workers with the lowest levels of education in the U.S. labor market earned. They typically endure long hours, face occupational health and safety hazards, lack health coverage, reside in crowded housing, and many of them live below the federal poverty guidelines. At least six percent of farmworkers identify as Indigenous, and for those without English or Spanish fluency, accessing medical care or information can be even more difficult. And while immigrant farmworkers are some of the most vulnerable to Covid-19 due to these circumstances, they have been deemed essential workers.

“It really shows that we as an economy and as a political system prioritize labor over laborer; we prioritize capital and profits over people,” says Stephanie Canizales, assistant professor of sociology at University of California Merced, who specializes in migration and immigrant integration. “We’re willing to protect people to the extent that we can extract profit from them, but not to the extent that would allow them to settle down, feel safe, and establish a secure future for themselves and their families.”

This inequity of including people in an economy for their labor and skills and yet excluding their humanity in narrative and policies is part of maintaining racial and economic power structures—and the nation’s food system was built on it.

EXPLOITIVE LABOR SYSTEMS BUILD BIG AGRICULTURE

“When you look at the history of agricultural labor in this country, for a long time it was done by slaves. And then once slavery was abolished, agricultural workers continued to face exploitative economic structures like sharecropping,” says Iris Figueroa, senior staff attorney for FarmWorker Justice, a nonprofit in Washington, D.C. In more recent history, those structures morphed into the recruitment of immigrant Asian and Mexican workers who have been denied basic legal rights through exclusionary policies and guest worker programs.

After the Mexican-American War in the mid-nineteenth century, the flow of emigration was primarily south. Mexican landowners and Native Americans were also forcibly removed through violence and government sanctioned discriminatory policies to make way for white settlers coming west.

But toward the 1890s, new industries drew in Mexican workers. During World War I when European migration to the U.S. declined, Mexican workers were recruited by agricultural employers via the country’s first guest worker program. The agricultural sector even lobbied to exempt this new workforce from the Immigration Act of 1924, which banned and established quotas discriminating against other immigration populations.

That changed, however, during the Great Depression and Dust Bowl, when drought pushed white farmers to sell their land and look for work in the fields. Over a million people of Mexican descent (at least sixty percent were U.S. citizens) were coerced by federal and local authorities to cross the border south under what was referred to as Mexican reparation.

During the establishment of the New Deal, labor laws were put in place to protect American workers, but they excluded protections for domestic and agricultural workers. “They were left out of minimum wage protections, they were left out of overtime protections, the right to unionize,” says Figueroa. “And not coincidentally, agricultural workers have historically been African American, Latino, and Asian American workers.”

A current problematic structure in our labor system today is the H-2A program, which allows migrants seasonal visas bound to a specific employer—meaning workers can’t keep their immigration status if they want to switch jobs for better pay or to escape workplace abuses. “It doesn’t take an expert to see that creates a power imbalance and a situation where workers are not going to want to speak up because of the consequences they could suffer if they did,” says Figuerora.

The H-2A program is a derivative of the infamous Bracero Program, which at its peak relied on the brazos, or the arms of 400,000 Mexican workers per year to power the agricultural sector during and after World War II. Under the program workers suffered widespread abuse, unsafe housing, and were cheated out of wages.

Currently, ten percent of farmworker labor (amounting to 250,000 visas in 2019) is done through the H-2A program. Workers have reported wage theft, squalid housing conditions, debt servitude, and lack of enforcement of legal protections. H-2A workers are also paid some of the lowest wage rates in the U.S. labor market.

The power dynamic is similar for undocumented immigrants, who work under the threat of workplace raids or U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrests and have no labor protections.“Your ability to speak out about pesticide exposure, about wage theft, about whatever else might be going on in the workplace is completely curtailed by the fact that you have the threat of immigration enforcement hanging over you,” says Figueroa.

INTEGRATIVE ECONOMICS CREATE A FLOW OF IMMIGRATION

But why have immigrants from Mexico, and more recently Central America, left their countries in the first place? Policies designed to increase trade between countries have played key roles in displacing people from their jobs and foodways south of the border.

Formed in the nineties, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) allowed U.S. products like corn, the staple of Mexico, to be imported and sold into Mexico at a cheaper rate than Mexican-grown goods. It also meant U.S. corporations were able to develop their own farms, displacing Mexican farm owners. “In integrating economies, the U.S. essentially displaced Mexican workers,” says Canizales.

Since NAFTA, the rural poverty rate in Mexico has increased, and almost two million farmers have abandoned the countryside with many of them heading to the U.S. In the five years after NAFTA took effect, illegal immigration increased seventy-five percent.

Opening markets also changed how Mexico eats due to a flood of processed food coming from the U.S. The shift has been linked to wide changes in health, and in 2016 the Mexican government declared obesity and diabetes epidemiological emergencies.

While violence in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala has driven up migration to the U.S. since the 1970s, the 2005 signing of the Central American Fair Trade Agreement (CAFTA) combined with drought and other climate change factors have contributed to economic hardship for communities that depended on farming. The number of immigrants in the U.S. from those countries rose by twenty-five percent from 2007 to 2015.

IMMIGRATION REFORM IS FOOD SYSTEMS REFORM

Despite the Trump administration’s campaign for stronger borders, immigration from Mexico has decreased since the 2008 recession. Undocumented immigrants are mostly settled here, with two thirds living in this country for at least ten years and twenty percent for over twenty years.

The slower flow of exploitable migrant labor explains why farm employers are lobbying for an expansion and deregulation of the H-2A program. “When comprehensive immigration reform has been on the table that has included a possible path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants, the one demand from the business community has been for bigger guest worker programs with fewer rules,” says Daniel Costa, Director of Immigration Law and Policy Research at the Economic Policy Institute.

As of late June, the Trump administration virtually shut down the immigration system apart from agriculture guest worker visas and a few other exceptions, citing the familiar excuse of protecting American jobs during economic crisis. But it’s U.S. employers—not immigrants—that limit lifting the floors for all workers.

“If you raise standards in guest worker programs and legalize the undocumented population, then you reduce that ability of employers to push down wages and standards for everybody,” says Costa. “It should really be a common cause of solidarity; immigrant workers and U.S.-born workers, especially in the low-wage sector, have a lot more in common than not.”

Policies creating pathways to citizenship could not only disrupt how low-wage workers across sectors are treated and paid, but also help transform the U.S. food system. Immigrant farmworkers have long been leaders in improving labor and environmental policies. For instance, the farmworker justice movements of the sixties and seventies were on the forefront of educating the public about pesticides and strengthening regulations. Today, as workers from the fields to food processing plants continue to feed the nation, it’s immigrant workers and coalitions of advocacy groups that are raising awareness and filing complaints against hazardous workplaces and racial discrimination.

Immigrant farmworkers and farmers also have skills and knowledge that could revitalize the way the U.S. grows, distributes, and eats food. As the pandemic brings the problems of the U.S.’s industrialized food systems into the spotlight, immigrants with agricultural expertise could be instrumental in building a more sustainable and resilient food system.

“We should definitely see immigrants and refugees as not just disposable or dispensable people in the fields,” says Vanessa Garcia Polanco, the Federal Policy Associate of the National Young Farmers Coalition, whose background as an immigrant has shaped the way she’s studied policy and advocacy in food systems. “But also people who come with a lot of knowledge and skills; and they can make our food systems stronger because we will have more diverse participation, diverse crops being grown, diverse ways of growing and diverse ways of eating.”

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.