Editor’s Note: This story is published in The What We Carry Issue of Life & Thyme Post, our exclusive newspaper for Life & Thyme members. Get your copy.

New Orleans has no shortage of culinary history. Great chefs like Leah Chase and Paul Prudhomme left the city with an enduring legacy to share. The city’s vivid architecture paints a picture of New Orleans past and present, and restaurants dating to the 1800s tell the tale of a city touched by Indigenous and international influences, converging in a cuisine that elicits an equal share of curiosity and envy.

It’s easy to assume that history exists in the past, but in the iconic French Quarter, a sweets shop reminds us that history is being made daily, often by the very people who make New Orleans what it is.

At Loretta’s Authentic Pralines in the French Market, lines steadily form upon the morning opening. Among the legendary pralines, patrons also stop by for crab and praline-stuffed beignets, pastries like apple turnovers and banana nut muffins, and the shop’s legendary sweet potato cookies—the stuff of New Orleans folklore. The abundance of sugary offerings makes Loretta’s a generally sweet place to be.

But a recent tragedy striking the heart of the business punctured a painful wound into the business. In February of this year, owner and business matriarch Loretta Harrison passed away at 66 after a difficult battle with cancer. The baker’s death sent shockwaves through the community, as Loretta had become synonymous with New Orleans culture.

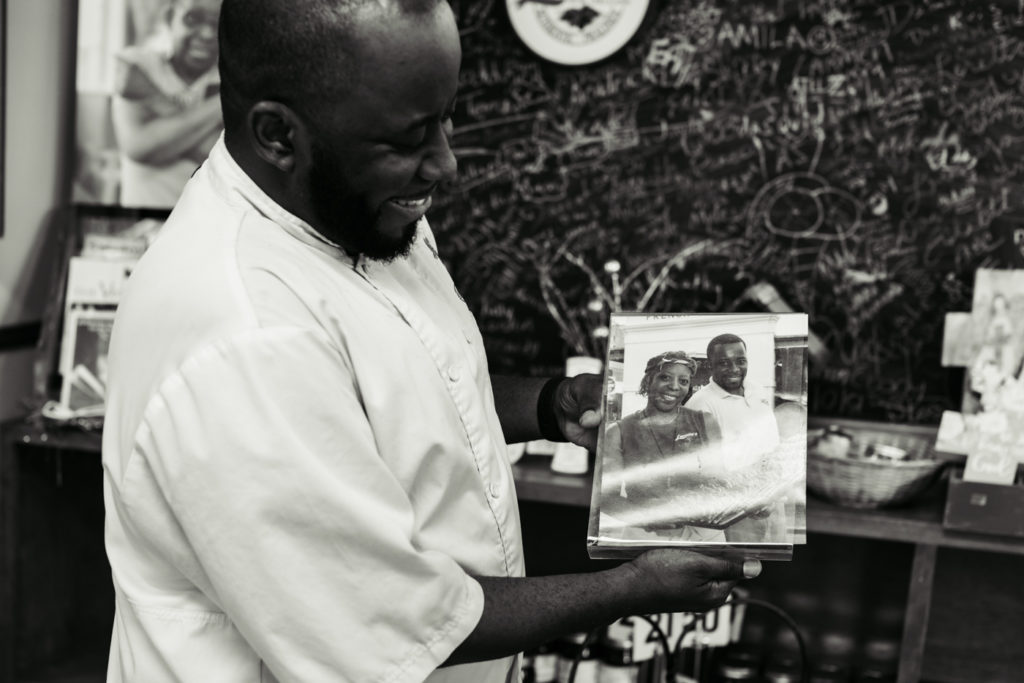

“When she passed, there were a lot of people who came to see us at the booths just to give their condolences,” Harrison’s son Robert recalls of recent experiences at two New Orleans festivals. “That was a good feeling. A lot of people had relationships with my mom through her product and through her spirituality.”

Harrison’s passing received a fair share of local coverage, and nearby mourners shared condolences at the shop daily (“She didn’t have customers; she had relationships,” Robert reminds me). Rather than focusing on her life, locals instead focus on the incredible institution Harrison built. Harrison owned the first and only praline shop owned by a Black woman in New Orleans.

“She was a phenomenal Black woman, and that’s why people are still showing up,” Robert says.

Raised in St. Bernard Parish in Louisiana, Harrison graduated from historical Black college Southern University. Like many South Louisianans, Harrison grew up eating pecans regularly. Early on, her business acumen was evident. Recognizing the local love of pecans, she would visit her grandmother’s house, gather a bunch of pecans from her grandmother’s tree, go to a local market, and sell them to vendors who wanted to sell authentic pecans.

When Harrison got older, she built on an old family recipe for pecan candy, or “pralines,” a regional delicacy that is a heavenly disc of sugary, buttery, pecan goodness. She developed a recipe for exceptional pecan pralines, and after a series of jobs, including a role at a New Orleans library, Loretta opened her own candy store.

“She was a young woman who wanted to be her own boss and saw the opportunity in New Orleans in the South with the praline,” Robert says.

Loretta’s Authentic Pralines became a mainstay of New Orleans culture. Harrison, a quick learner, became a skilled baker and introduced devilishly good variations of pralines, like rum and chocolate. She created her own iterations of fudge, pies, cookies and even calas, an old Creole dish of sweetened rice dumplings.

Loretta’s confections, according to Robert, have been served just about everywhere. She was always at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, better known as Jazz Fest (“Never missed a year.”), local festivals (“Everyone loved her!”), and even sweetened a few presidential inaugurations (“It’s Barack Obama, the first African American president! You know we had to represent.”).

In the 1990s, however, life was a bit different. And for a while, Loretta was, at least to most New Orleanians, an invisible figure.

—

“It’s very interesting, but I could definitely cut it to you straight: nobody knew the face behind the name,” Robert recalls of a different time in the store’s history.

Although Black people are critical to Creole and Cajun cuisine and New Orleans foodways, their contributions have often gone overlooked.

“Black involvement in the New Orleans Creole cuisine is as old as gumbo and just as important,” wrote Chef Nathaniel Burton and author Rudy Lombard in the groundbreaking book Creole Feast: Fifteen Master Chefs of New Orleans Reveal Their Secrets. The writers continue, “It is unfortunate that local attitudes toward racial matters have not allowed the contributions of Black people to this cuisine to achieve the kind of prominence they deserve.”

While Black folks haven’t received their rightful appreciation for their contributions to New Orleans Creole cuisine, it’s impossible to not see their impact across the city’s foodways. While Loretta was the first Black woman to open a praline shop in New Orleans, she follows an important legacy of Black women who popularized pecan candy in the region as one of the city’s earliest street foods.

When Harrison founded Loretta’s Authentic Pralines in 1983, turning a profit was a priority. Instead of being especially visible, Harrison was usually in the kitchen, looking at customers through the window. Because she wasn’t taking orders or speaking to customers—and the store opted to emblazon pecans as their store icon rather than her face—many people didn’t know what Loretta actually looked like.

“The store was her baby, and she wanted people to see the product,” says Robert.

Eventually, Loretta became more comfortable with a public persona. She started doing demonstrations at festivals and shows, but many white customers still didn’t make the connection that the person who owned their favorite praline shop was a Black woman.

“I think they saw a young Black woman and said, ‘Maybe she manages it or something.’ They didn’t put two and two together until the late ’90s,” Robert says. “By that time, my mom had blown up—like she was out of the country pushing her candy.”

Loretta’s products, and her charming and warm persona, became one of the crowning jewels of New Orleans. Not only was she producing local confections that were shipped as far as Switzerland, but as her identity became increasingly public, she was showing that Black women were integral to all that New Orleanians love about their food and culture.

“Miss Loretta is a Black woman. First African American candy business in New Orleans, and they just now figured it out,” says Robert. “She identifies with all people, though, and when people started to see her at the festivals, it just took off after that.”

Now, Loretta’s family takes the reins of the historic business. Robert and his family members have come together to make sure to follow through with Loretta’s primary request: to keep the business going.

“She sat us down, me and my brothers,” he explains. “And she was like, ‘Okay, legacy is set. Now it’s your turn to continue.’”

Although Loretta is no longer in the French Market to welcome visitors, her presence is still felt at both shop locations. You’d be hard-pressed to not see someone grinning ear to ear as they brush beignet sugar off their bottom lip, or some patrons’ eyes roll back in pleasure upon the first taste of a praline. And yes, New Orleans kids do love them some sweet potato cookies.

“It’s the family recipe and people come from all over,” Robert says. “They want that cookie.”

But for Loretta and her family, the shop has always been about more than sweets. It’s about the idea of embracing the old and new, and demonstrating the culinary and entrepreneurial capacity of Black women.

“I tell her story twofold,” Robert says. “She was a woman because she had to go through barriers to own her own business. She was a Black woman because nobody was going to just give it to her.”

“The people who are the trailblazers—you have people who are influential Black people in the South—who not only paved the way for the next generation, but they put in some serious hours,” Robert continues. “Loretta was one of those people.”

And really, is there a sweeter way to remember this history than through a bite of a praline?

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.