The Pizza Issue, April 30, 2019

Pizza Primer

An exploration of some of the world’s most famous and favorite pizza styles.

Words by Stef Ferrari

Illustrations by Lori Bailey

I love pizza. Pure, blissful, Ninja Turtle-level love. I love the way it tastes and what it represents, in terms of nostalgia, memory and Americana. I love the comfort of a piping hot slice or square, I’ve loved it as school lunch, family dinner, or a late-night snack—even served cold as reheated breakfast leftovers. I love the taste, but also contemplating its tradition, where it comes from, and the creative liberties makers take with it today—a perfect platform for experimenting with just about every ingredient and flavor combination imaginable.

I will enjoy pizza in almost any form or circumstance, but one thing in which I will not indulge is a conversation that starts with, “What’s your favorite kind?” They’re all so vastly different, each with its own individual merits, that it’s impossible to choose; and honestly, why would you want to limit your prospects at pursuing pizza happiness?

What follows is a very condensed primer on all things pizza, because the way I see it, there’s a pie for every mood, place and time. I was raised twenty minutes from New Haven so I have special affinities there, but I also feel an allegiance to Roman-style pizza al taglio, being of Lazian descent. And although I have never been to Detroit, I can absolutely enjoy a pan pizza that bears its name, and I will never say no to a slice from old Napoli. Being able to appreciate the specific bliss that comes along with each style, now that, my friends, is amore.

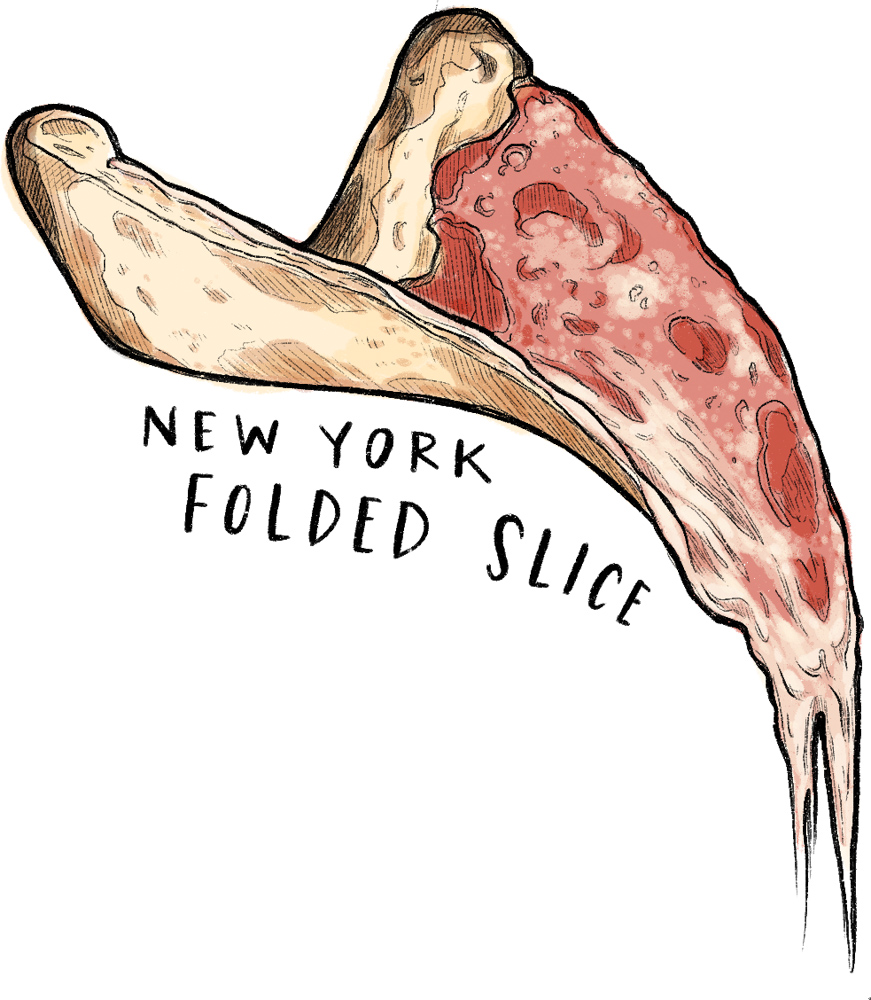

New York style pizza is probably the most commonly recognized, and is what comes to mind for most of us when we think of pizza. Today, it seems as if every city in the U.S. has a “New York style” pizza spot, but if you want a slice of the real deal, you’ve got to get yourself to the Big Apple.

Typically, a thin crust is hand-tossed (although rarely with the kind of flair we romantically imagine). The classic topping situation is a layer of tomato sauce and shredded mozzarella cheese, but a range of other toppings are commonly available—especially pepperoni.

Some credit New York City municipal water for the perfection of New York pizza, and argue it’s the main reason it can’t be replicated outside of the area; but perhaps one of the most important characteristics about New York pizza isn’t flavor—it’s functionality. For a town that’s all about getting shit done, it’s no surprise our meals are often taken on the run, before or after or in between something or somewhere else. To that end, the humble pizza pie must stand up to being carved into portable slices, engineered to fold easily and not fall to pieces without the support of a plate.

At one time, New York easily had the market cornered on the pizza game, but it clearly and historically owes its evolution to the adaptation of neapolitan style.

Notable purveyors: Lombardi’s, Joe’s Pizza, Totonno’s

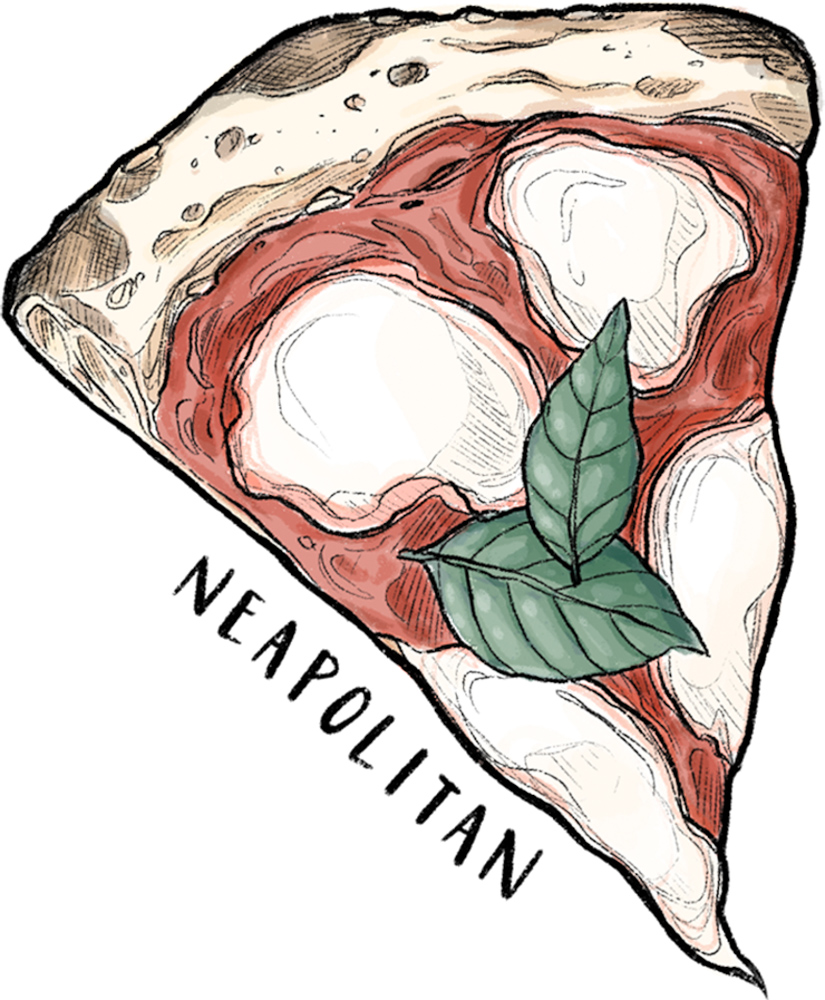

Most commonly called the birthplace of what we consider pizza, Naples has been turning out flatbread topped with cheese and sauce and all the wonderful things for more than three centuries. The pizza is so tied to the city’s identity that as of 1984, Neapolitan pizza has an official, protected designation with the The Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (VPN).

In addition to other strict guidelines, San Marzano tomatoes (grown in volcanic soil) are the only acceptable varieties here, along with two options for cheese: fior di latte or mozzarella di bufala. Because of the intense heat and short cook time, the center of a Neapolitan pie is wet and doesn’t hold up to the folding treatment to which a New York slice is often subject. It’s a bubbly, sometimes blackened crust—made solely with salt, yeast, water and flour—that comes out with a touch of chew.

Pizza Margherita came from Naples, where accepted lore has it that Queen Margherita visited Naples with her husband, the King of Savoy, for summer vacation in 1889. A local pizzaiolo, Raffaele Esposito of Pizzeria Brandi and his wife, took the opportunity to make a name for their little restaurant, and created a dish just for her based on the Italian flag: green basil, white mozzarella, and red tomato sauce. Another classic has Neopolitan roots: marinara suggests the sauced pie was created for the fisherman working the ports of Naples.

Notable purveyors: Pizzeria Brandi, Pizzeria Carminiello

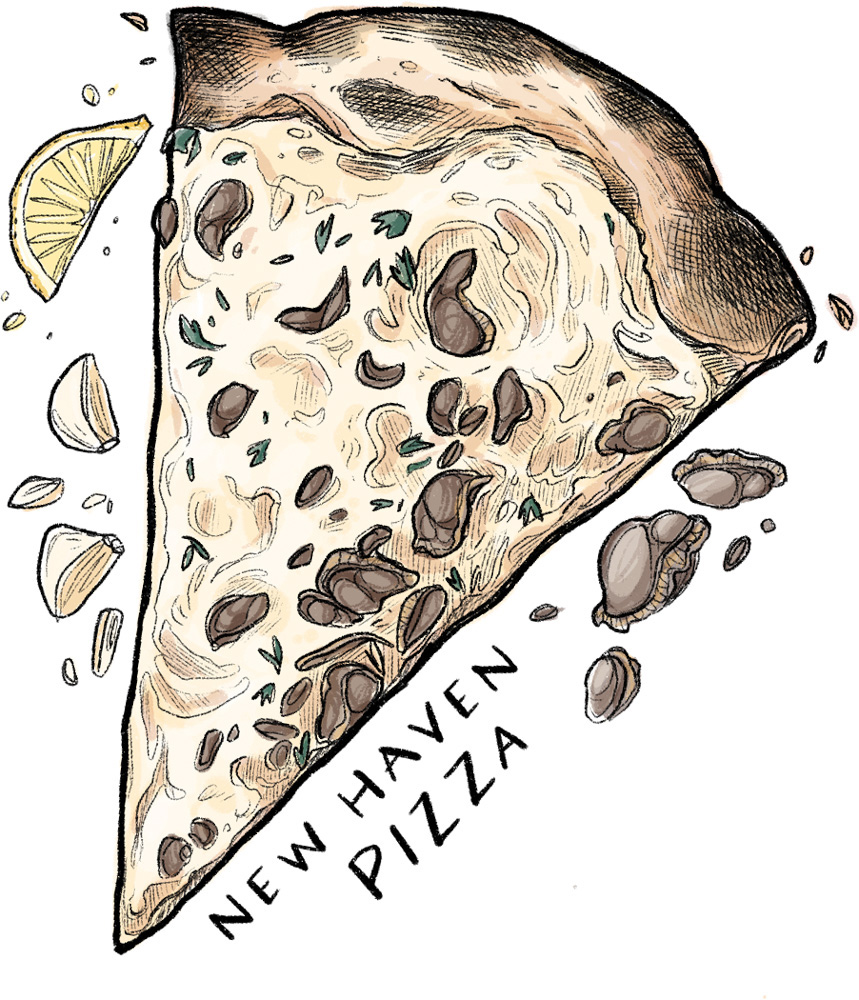

As a Connecticut-born pizza lover, this style is a personal favorite. Characterized by charred crust, it hews more closely to the inspiring neapolitan style than New York’s interpretation. One of the major points of differentiation in New Haven pizza is technique: few pizzerie still have access to and use of the kinds of ovens that are required to turn out these iconic pies. These coal-fired brick ovens get incredibly hot, which means in just around ninety seconds, the edges emerge blackened, soot covered from decades of the oven’s seasoning.

This pies are blistered, spotted with black bubbles and concentrated tomato sauce, they’re sooty and smoky. It’s that bitter char contrasting with tangy, sweet tomato, and salty pecorino cheese that typifies the experience, and it is my personal opinion that if you don’t leave one of these spots with slightly black fingertips, you really haven’t done your job as a diner. Traditionally in New Haven, mozzarella is a topping available on request—not at all a given. Tomato pies are still standard, but meatballs, sausage and veggies are there for you upon request. New Haven is also home to the ultra-controversial white clam pie, which, with grated cheese, garlic and salty bacon, should really give no one any reason to argue why it exists.

Frank Pepe is usually the man who gets the credit for setting up shop on Wooster Street in the 1920s, but now there is a whole network of New Haven-style joints doing apizza (pronounced more like “a-beets” by the locals). Wooster alone is home to Pepe’s, Sally’s, and The Spot, but if you venture a bit off the epicenter of the Italian enclave to State or Crown Streets, you’ll find Bar (which also brews beer on site and is famous for its mashed potato pie) as well as my personal favorite, Modern Apizza.

Notable purveyors: Frank Pepe, Sally’s, Modern Apizza

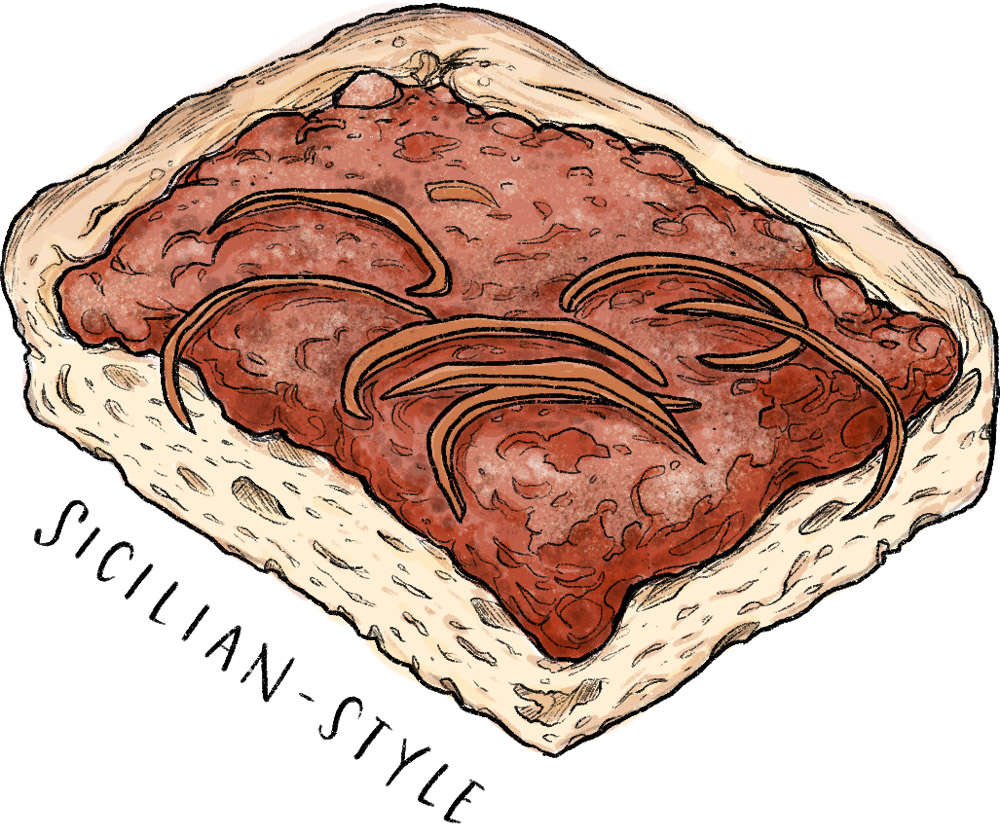

This is the square pizza most of us are most familiar with, but the thick and airy style wasn’t always served with corners. Sfincione (which is what the Sicilians call Sicilian pizza, and translates roughly to “thick sponge”) is sometimes found in a more familiar round form as well, and is an evolution of focaccia.

Although it doesn’t always call for a tomato component, when it is employed, traditionally sauce ingredients have taken cues from the island’s cuisine and included onion, anchovy and herbs. In this scenario, pizzerie take an inverted approach, layering the wet ingredient on top of the cheese, which acts as a barrier to keep the doughy crust from becoming too damp. This approach also allows the sauce to cool down during the baking process, resulting in an umami-rich, super concentrated red sauce with the added funk of anchovy.

An ideal slice of Sicilian pizza has a crisp bottom that crunches a bit in contrast to the otherwise chewy, more bread-like layer, after baking in an aluminum pan. Sicilian cheeses are often made from sheep and goat’s milk, although Caciocavallo, a hard, cow’s milk cheese, is common for these pies. The stateside version is typically topped with the more available mozzarella, and a more straightforward tomato sauce made anchovy-free for the American palate. The derivation of the style in the U.S. is typically quite thick—sometimes up to an inch.

Long Island, New York, is also getting credit these days for popularizing a variation on the Sicilian known as the grandma pie (or, pizza casalinga, meaning the “housewife”), and is differentiated by the fact that it isn’t left to proof—Sicilian pies rise sometimes for up to seventy-two hours— and is rather baked right away, resulting in a slighter thinner, denser finished product.

Notable Purveyors:

For Sicilian: L&B Spumoni Gardens

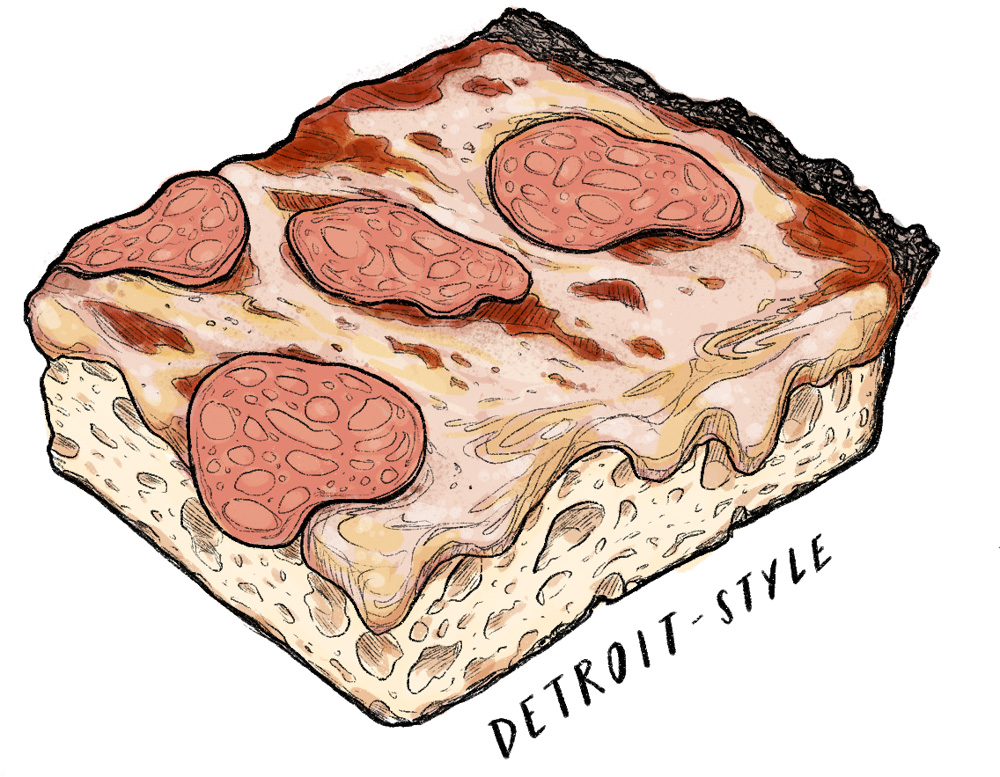

Like most things that come from Motor City, the story of this pan-style pizza has a direct link to the area’s deep car industry legacy. A derivation of Sicilian-style, the legend says that original iterations were actually baked in spare, blue steel automotive part pans brought home by industry workers. Buddy’s Tavern generally gets the credit for this creative adaptation of equipment in the early 1940s when the owner, Gus Guerra turned his mother-in-law’s recipe for a quick at-home pizza into the makings of a movement.

From there, Sicilian inspiration was subject to change based on ingredient availability. Guerra used a process Wisconsin-made product known as “brick” cheese (certainly a far cry from the pecorino at origin). The pizza is baked first without sauce—simply a fluffy dough pressed into the pan with a thick layer of grated cheese. During the baking process, the edges of the pie crisp and the cheese caramelizes—arguably the Detroit pizza fans favorite part, and the cause for many arguments about who gets the corner piece. Once pulled from the oven, two “racing stripes” of fresh marinara are ladled over the top, in what is said to be another nod to automotive roots.

Today’s producers have branched out from those Michigan origins, and are experimenting with the style, swapping old-school brick for small batch artisanal cheeses, changing up the classic toppings and spreading sauce more liberally over the finished pie.

Notable purveyors: Buddy’s, Luigi’s Original, Lions & Tigers & Squares, Emmy Squared

When we refer to pizza as “pie,” perhaps this is the style that most deserves the moniker. Here, the term “flatbread” doesn’t really apply, as the finished product probably has more in common with a casserole.

Although it bears almost no resemblance to anything found in Italy, the Chicago pizza does in fact have Italian roots. There is much debate about who can take credit for its invention, but most accounts credit an influx of immigrants to the city in the mid-twentieth century including entrepreneurs Rudy Malnati, Ric Riccardo and Ike Sewell, and their ambition to reinvent the classic combination of crust-sauce-cheese in a totally new format.

Their innovation has begotten a class of pizza baked a high-walled vessel that could probably double as a cake pan. The crust itself is pressed to create a kind of bucket shape which can contain the heavy toppings. In order to create a sturdy foundation, the crust must be parbaked before layering in the contents: layers of cheese (A Chicago pie can have up to a full pound of mozzarella), meats, more cheese, tomatoes, and sometimes vegetables like peppers and onions. Some deep dish makers opt for butter over olive oil, but in either case the shell gently fries to a delicate, flaky crunch during the cooking process. The crust displays a golden tint thanks to the chosen cooking fat, which has become such an integral part of the pie’s identity that some pizzerie have been known to add artificial coloring, to deepen and emphasize the hue.

Slices are served with a spatula—no folding here—and usually require the use of a fork and knife.

Notable purveyors: Pizzeria Uno, Gino’s Pizza, Pizano’s, Lou Malnati’s

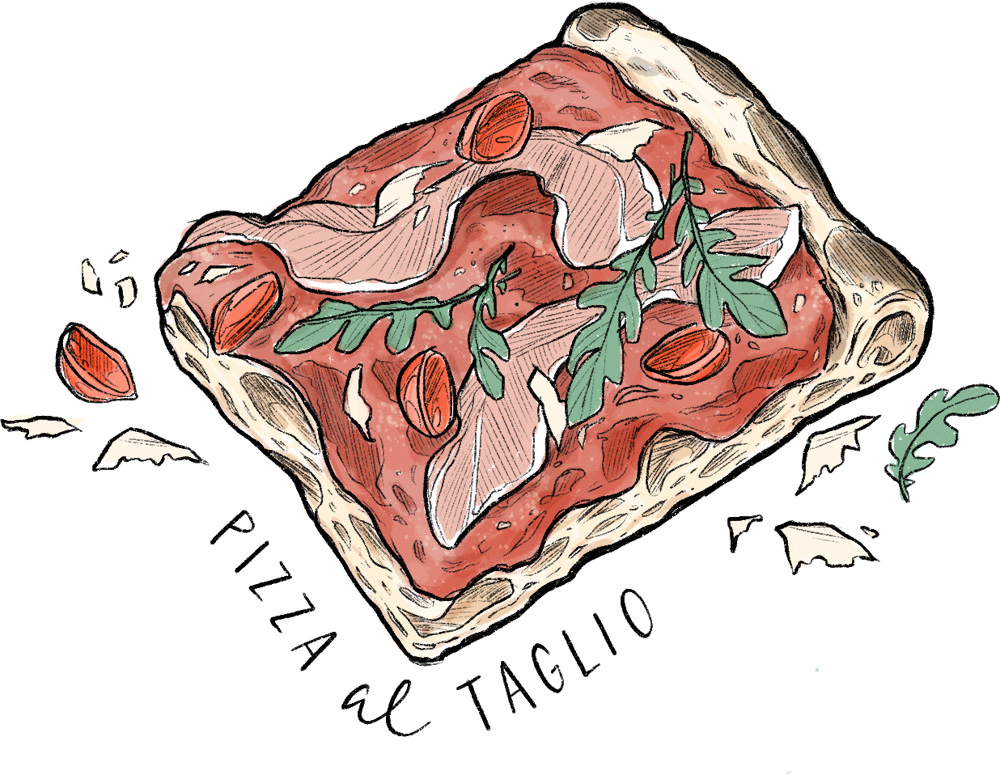

Traditional Roman street food runs the gambit. You can find freshly cut and fried artichokes, baccala (fried cod), maritozzo, and gelato for the sweet tooth. But pizza al taglio is the king of the Roman road.

“Pie” doesn’t really apply to this style either, as each option is presented as long, narrow focaccia-esque belts. The name translates to “pizza by the cut,” and is a slice to order situation (although it is occasionally called pizza al metro, referring to the meter-long length of the full pizza). In these shops, patrons simply point to the pie that interests them, give a general sense of the size they’re looking for, and then pizza is then cut, weighed and priced by the gram.

While bianca (olive oil and salt) and rossa (sauce, sans cheese) are classics of course, toppings can run wild with al taglio. On a recent trip to the Lazio region of Italy, I filled my tray with slabs of the following: zucchini and eggplant, amatriciana, potato and rosemary—even zucca (pumpkin) and chicory. In contrast to most styles of pizza in which toppings are piled on and cooked, these pizzaioli are cognizant of how a longer oven time might impact their choice of ingredients, and sometimes make a judgement call to add certain items during or post-cook—a clear example of Italian inclination to spotlight quality ingredients in the most optimal way.

A resurgence of popularity for the style has come thanks to a new wave of Roman pizzaioli. chefs like Gabriele Bonci lead the charge with locations in the United States as well, serving classics and creative spins, even catering to vegan and vegetarian pizza-lovers.

Notable purveyors: Pizzarium, Bonci (Rome and U.S. locations), Pizzeria La Boccaccia

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.