In 1969, two inventions arrived on the world’s stage. The first—a major feat of science and technology—was the supersonic jet. The Concorde was a needle-nosed phenomenon that captured global attention at warp speed, having the ability to travel at more than twice the velocity of sound. It signified huge progress in transportation, invention and beyond that, international relations. Its name, meaning union, was intended to highlight the relationship between the British and French, which co-developed the aircraft as part of an international treaty.

The second feat was itself a kind of union—one of sugar and technique. Perhaps a bit humbler, but no less impressive, French chef Gaston Lenôtre, invented the Chocolate Concorde Cake in celebration of that aircraft. This thing was a serious study in edible architecture. Delicate but sturdy circles of crisp meringue act as structural scaffolding for layers of densely creamy chocolate mousse. With equal attention to construction and decadence, function and flavor, it was a poetic homage to the plane’s launch.

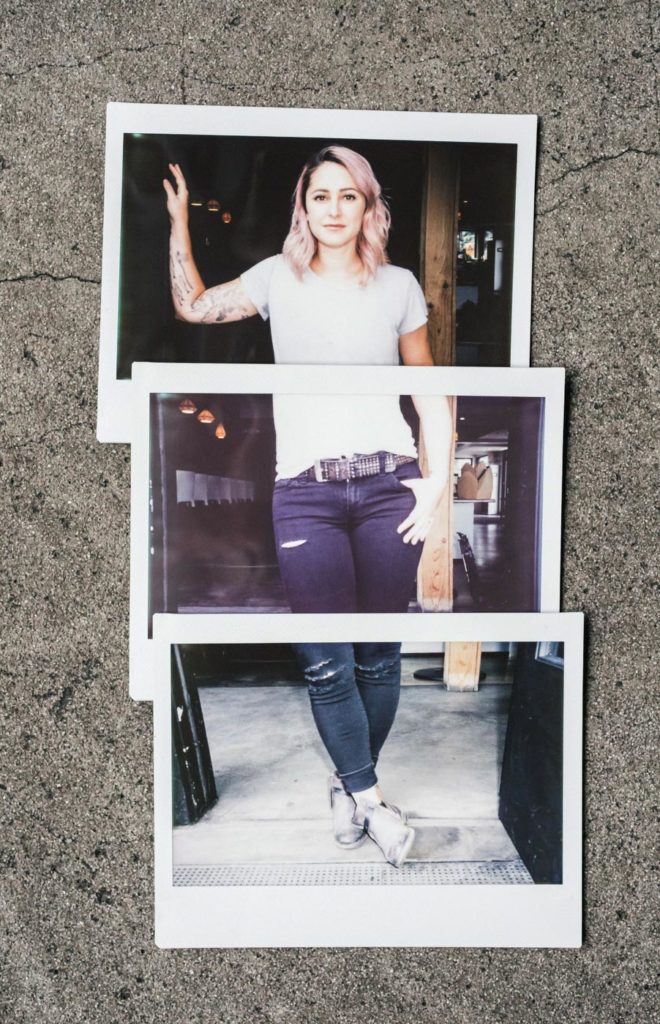

It’s fitting then, that not long after learning to execute of a version of this very cake—nearly six thousand miles from its place of origin and a several decades later—Chef Brooke Williamson’s career took off.

——

I think Williamson would agree that the first time we met, it was a fairly uncomfortable experience for us both. Not on account of the company—that part was lovely. But despite sitting in a brand new BMW, the circumstance was absolutely anything but luxury.

We were attempting to capture an audio interview with Williamson for a collaborative project—and that’s a pretty tricky thing to do among the condensers and cacophony of a kitchen. Instead of her restaurant’s comparatively balmy prep space, we set up in a colleague’s sedan, where we found that even an idling engine or running the air-conditioning contaminated the sound. And so, with windows sealed and the engine off, we sat in a sweltering vehicle beneath a scorching Southern California sun, take-after-take trying to stifle the punch-drunk laughing fits that come with being borderline heat-poisoned.

By the time we sit down together inside her restaurant nearly two years later, we’ve come a long way, both comfortably hydrated, sweaty glasses of ice water between us. We’ve since crossed paths on a number of projects, including Life & Thyme’s Doyenne exhibit, to which Williamson—among other prominent L.A. female chefs—donated her time and food to help raise money for Planned Parenthood earlier this year.

And beyond all that, quite a lot has happened in Williamson’s world. She opened a poke spot called Da Kikokiko. She expanded her ice cream concept, Small Batch, into a stand-alone shop. She’s cooked all over the country. Oh, right, and she was crowned champion on a little show called Top Chef, outperforming her co-contestants in all manner of culinary challenges.

In fact, trial by fire seems an igniting force for Williamson. It’s how she kicked off her professional life, taking a job as a pastry assistant—a part of the kitchen world in which she was not at all at ease—just to get her career off the ground. “The moment I was old enough to work in a restaurant, I worked in a restaurant,” she says of her first job at Fenix in Los Angeles’ The Argyle Hotel. “The chef was Ken Frank. I walked in and said, ‘I’ll do anything for free.’” Of course, Frank couldn’t hire her for free, but he he did need a paid hand in pastry.

Among the first items she was expected to learn? The Chocolate Concorde Cake. “You had to make meringue disks and layer it with this really thick chocolate mousse that would hold the cake, and when you took a bite, it would just melt in your mouth,” she tells me.

But it was with those individual lessons that Williamson began building her expertise. “I never intended to be in pastry; I’m super thankful that I know [it] now. I feel like it makes me a little more versatile,” she says.

It was an early lesson in diversity and adaptability, both of which have been recurring themes for Williamson as a chef and later a business owner—themes perhaps no more evident than sitting inside Playa Del Ray’s Playa Provisions. Observing the sprawling multi-concept space is a little like getting a look inside Williamson’s head. Housed in one building, five separate spaces are operated—counter market King Beach, the ice cream concept Small Batch, a whiskey bar called Grain, and Dockside, a full service dining experience, as well as the recently added retail area dubbed Tripli-Kit. And this is just one of the establishments she co-owns and operates with her husband, Chef Nick Roberts. The couple also count the area’s Hudson House, The Tripel, and Da Kikokiko under their umbrella. All in addition to Williamson’s other full time gig—mother to their nearly-ten-year-old son.

Williamson will tell you she has wanted to cook since before she was his age. That she eschewed Saturday morning cartoons in favor of Julia Child and The Galloping Gourmet. And that while her concepts are prismatic, her focus has always been pointed; by the time she finished her stint in the Fenix kitchen, her career went into hyperdrive. At age nineteen, she was the youngest sous chef in the history of the iconic Michael’s Restaurant in Santa Monica, and within a few years, she and Roberts were opening the first location of their own.

Becoming an entrepreneur was yet another crash course. “We opened our first restaurant when we were twenty-four years old, and within two years we were closed. We poured our heart and soul into that place,” she tells me. “I cried so much when we had to close the doors.”

Fortunately, Roberts and Williamson were able to see the writing on the wall, and began to plan their second restaurant before the first was closed. Since then, the food industry has entered uncharted territory time and again. For the couple, their ability to sense changing headwinds—their resilience and multifariousness—has been the difference between staying airborne or succumbing to turbulence.

——

In the late 1990s, it became clear that the Concorde jet company had a problem. For as flashy as it was, for as fast as it could go, they had a hard time bringing in return customers. Passengers wanted to say they’d made the trip—to check off the experience—but it wasn’t considered something they could repeat with any regularity.

It’s a problem that restaurants, decades later, are experiencing thanks to their own era’s rapidly evolving technology and diminishing attention spans. “[Diners] are always looking for the next shiny thing,” Williamson says. “I know I’m not the shiniest thing out there, nor do I try to be. I’m not trying to reinvent anything.”

Williamson wants to cook what people want—and will want regularly. For example, “[Da Kikokiko] is a very specific concept, but it’s also something I want to eat every day of my life. That is about sustainability and having something people depend on and want on a regular basis and crave.”

Clearly, the restaurant world is not in quite the same stratosphere as the aerospace industry, but it’s not uncommon now to find some meals cost as much as a transatlantic flight. Where people decide to spend their money and their time is increasingly fractured, the market flooded with options thanks to skyrocketing consumer interest. What gets people in the door once isn’t always what continues to fill seats. “It’s the repeat business that keeps you alive. It’s this neighborhood. The person across the street who comes in and gets a happy hour chardonnay and biscuit night—those are the people who fill up the room and make this feel like an exciting place.”

Williamson’s natural predilection for a variety of pursuits has also served the couple success. “All the different outlets are a really phenomenal way to help me not get bored,” she laughs. “I love the ability to be creative. I love that no matter what I’m inspired by at that moment, I now have an outlet for that regardless of what that is.” But beyond being a creative runway, it’s integral to the business strategy. “It’s also a solution—us trying to find a way to stay relevant and stay alive because we’re very aware that restaurants have a lifespan. It’s maximizing every moment we could possibly be open.”

Theirs is, at its core, a family business—one that benefits from the financial practicality of multiple revenue streams. “Nick and I are not relying on taking one paycheck from one place. We’re now to a point where we take a small salary from each place and that pays for our lives; but if we had to take a full blown salary from the poke place or the ice cream shop, we couldn’t do it.”

In a sense, Williamson and Roberts are piloting a new kind of mom-and-pop model, but what fuels their business is something identifiable regardless of trend or generation. “This industry is risky enough and I feel like having an almost ten-year-old kid, that kind of pressure—to give him an actual stable lifestyle—is really important to me,” she says.

Operating so many concepts means stepping away from the control panel perhaps more than Williamson cares to. “We’re about to open our fifth spot, and they’re all within twenty minutes of each other,” she says. “Yes, I understand I have let go most of my control over everything because I had to, but I also know if I have to be somewhere in twenty minutes, I am able to get to everything.” Having the restaurants clustered also allows her to be a presence for her patrons. “I really take pride in what I do and what I offer people. I need to be able to be a part of it and have customers come into my restaurant and [see me] there.”

The idea of presence is on the minds of Williamson and many of her contemporaries, for whom it seems ancillary projects, which often draw them far from their respective restaurants, are increasingly important. In fact, it’s too bad the Concorde is no longer in operation—Williamson’s travel schedule is often packed with collaborative dinners, regular support of nonprofit efforts, appearances at food events all over the country, and endorsements, all of which Williamson acknowledges are “huge” in terms of supplementing and promoting the core business. “I will never represent a brand I could not stand behind,” she says. “But at the same time, that stuff keeps it going. It’s publicity, but it’s also great for sending my kid to school. I’m fortunate enough to have those opportunities.”

Given what a chef has to consider today to be successful, there is a question of whether it’s even possible to grasp the ever-elusive, so-called work-life balance. “Is it possible to do everything professionally, and all my hopes and dreams? If I want to continue to be a mother my child can depend on and is around more than once a month, then no, it’s not possible to do everything. But it is possible to do a lot of what I want to do,” she says. “To do it all really well? Who knows,” she laughs.

Today, it seems as if there are more questions than answers to being successful in the restaurant business, but just as the industry has changed, perhaps the definition of success has too. “When I started out, I was making $4.25 an hour and working sixteen hours a day, but I was excited to go to work,” she recalls. “I was paying for my life, living on my own, not depending on anybody for anything. That felt good.” Today, the signifiers of success are slightly higher stakes. “I’ve got a kid in private school, which I never really thought I’d be able to afford—which I can’t really afford,” she laughs. “Sending my kid to a great school was a huge, huge accomplishment for me.”

Quantifiable meanings of success aside, it’s what defines Williamson herself—being a mother, a chef, an entrepreneur—that clearly brings her daily satisfaction. But with increased media attention in the food world, the necessity to package a life’s work and passion into such press-ready soundbites can feel reductive. For Williamson and her contemporaries, another qualifier often attached is female, although she recognizes it as one that can’t be ignored. “It would be really ignorant to say it doesn’t matter. Of course it matters,” she says. “It made things more challenging, but it also was the reason why I was getting full blown L.A. Times reviews at the age of twenty-two, because I was like the youngest female chef in the city. If I was a guy, I don’t know if I would have been recognized like that. So it definitely has made a difference in my career.”

In Williamsonian style, the added challenge was her kind of fuel. “I think the landscape for women has changed a lot since I first started cooking. But I also loved the fact that I had to work harder, because if I got to a certain point in my career, it actually meant that I had to work harder to get there, and I had to prove myself more.” she says. “And I always found it as a point of inspiration and motivation rather than being unfair. It makes me feel stronger.”

——

When I step outside Playa Provisions, planes streak by above the beach across the street; we’re just ten minutes from Los Angeles International Airport. The Concorde fleet retired in 2003. The Concorde chocolate cake, with all its layered, contrasting textural allure, is hard to come by these days too. Both artifacts of a past generation’s ingenuity, not quite able to adapt and keep pace with the times. Getting off the ground is one thing, maintaining altitude is another. Some trends take off, while others disappear from the radar. But for Williamson, there appears to be no sign of slowing.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.