Author’s Note: Roots explores lesser-known stories of those who take a traditional approach to food to honor their heritage or to rediscover those useful, time-tested methods. These stories hone in on the lineage, history and perpetuation of cultural customs—or even the clashing of those values with the fast-paced life much of the world embraces today.

——

It was a crisp San Diego evening a few years ago when photographer Lauren di Matteo and I crossed paths with an Irishman for the first time. Approaching a nearby café, the undulating vibrato of an opera singer beckoned us inside. We squeezed into the very last table, and ordered drinks to warm our hands. As the steam swirled upward in unison with the melodies serenading us, a chorus of foreign languages rang out from every corner of the room. Friends and patrons, whose origins spanned the globe, greeted one another with hugs and kisses. Somehow, it was as though we were the only strangers in the room.

A faint trace of cigar drifted in from the patio, a fitting scent for the sight before us. Every wall stretching toward the vaulted ceiling was covered with ornately framed mirrors, antique paintings and old muskets from worlds away and years past. A local concert pianist inhabited a baby grand piano tucked in the corner, educating us on Tchaikovsky’s works between Italian arias.

We must have stood out—sitting wide-eyed, soaking it all in. A friendly Irish patron pulled up a chair and joined us, taking it upon himself to play host and introduce us to the key players in this old world café. The owner, the singer, the pianist and the room full of regulars—we met them all. They’d become long-time friends of his since he began frequenting this neighborhood café over a decade ago. Hours passed as we conversed about art, literature, music and philosophy—surely we had stumbled upon some sort of wrinkle in time. Moonlight and laughter waxed on into the wee hours of the morning, until the place had nearly emptied. A round of port was poured by the generous owner as a final adieu, followed by a farewell Irish tune from our new acquaintance, Colm Lynam.

A friendship has been forged with Lynam over the years since that memorable night, with occasional run-ins at the café that he frequents daily, just as he would a pub back home. He is a master in the art of conversation and as friendly as they come, greeting every passerby as he would a friend. It’s hard to believe he left Ireland over 20 years ago—apparently not all things fade with time.

With deeply ingrained values of generosity and hospitality, he once entertained us in his home for an entire evening with tales of his homeland and a savory Irish feast of roast leg of lamb, boiled potatoes and brown bread—Irish soda bread, that is. Steamy and warm, the bread was served right out of the oven and was so filling I could only handle one slice with the meal. It was tasty, yet somewhat unassuming. We wouldn’t begin to understand its significance to the Irish until a trip to the West Coast of Ireland the following year—per Lynam’s ardent recommendation.

Our host at the time had a beautiful, handmade wooden table in his kitchen, adorned always with a loaf of bread and a golden brick of Irish butter. He spent most of his days outdoors tinkering away, but when he came in, it was always for a piece of brown bread with a thick slathering of Kerrygold. Some days it served as breakfast all on its own. Others, an addition to scones and a true Irish breakfast of eggs, bacon, mushrooms, tomatoes and black pudding. Quite often, however, we lounged around the table for midday tea, eating a few slices with butter and jam, while discussing politics, history and current issues within Ireland. The bread served not only as delicious sustenance but as an avenue for connecting with a new culture—and various visitors who would stop by for a warm cup of tea and a slice or two.

The temperature has finally dropped here in San Diego, and the days are shorter. Misty mornings and chilly evenings bring to mind images of Ireland’s emerald landscapes, enchanted faerie forests and the warmth of Lynam’s friendship. We pine for that freshly baked soda bread and decide the long awaited arrival of baking season is the perfect opportunity to reach out to Lynam to catch up—and maybe even garner a recipe.

We meet in his neck of the woods and take to the streets, walking several blocks to a restaurant of his choosing. He grows a bit shamefaced, admitting it wasn’t until his early thirties that he attempted to bake soda bread himself. He called his mother in Ireland to request her recipe and, “She just laughed at me,” he says with a shake of his head. Undeterred by her response, he resorted to looking up recipes online and quickly understood why she thought his request ridiculous—most recipes call for only four or five ingredients. The bread is exceedingly simple to make, although he confesses that the art of getting it just right takes everyone a bit of time.

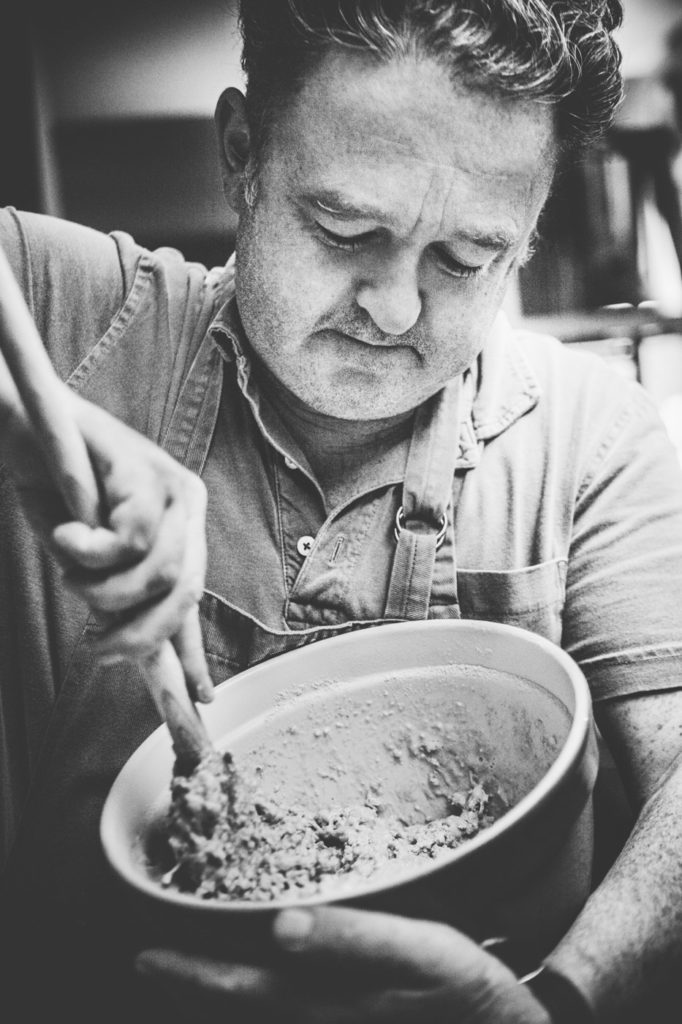

After dinner, we find ourselves unable to resist Lynam’s generous invitation to head toward his home straightaway to whip up a fresh loaf of Irish soda bread. When we arrive, he shows off his day-old brown bread that is wrapped in a small towel. Following in his mother’s footsteps, he bakes twice-weekly, refusing to purchase bread from the grocery store during the cooler months of the year. There are two versions of brown soda bread out there, and this is the dark, earthy one usually prepared in a loaf pan. A more complex soda bread, it is often made with the addition of molasses, egg and even wheat germ and oats, for a nuttier finish. Although it can be found all over Ireland, it remains fairly unknown in the U.S. Its hearty, thick slices are perfect for sandwiches or alongside a bowl of stew. I prefer them generously layered with smoked salmon.

Then there are the other, more ubiquitous soda breads—brown and white—which are made in a dutch oven or cast-iron skillet. Most brown soda breads are made with three parts wholemeal flour to one part white, with the white ones made of all white flour or a one-to-one ratio of white to wholemeal. Wholemeal flour is made of Irish wheat and fares best with baking soda over yeast. But unfortunately, the nearest equivalent we have to it in the U.S. is coarse-ground whole wheat flour; although less than ideal, it suffices as a substitute.

Another familiar soda bread is rather sweet, with the addition of currants and caraway seeds. It is generally recognized as the American—dare I say, bastardized—version of soda bread, blending Irish heartiness with the American sweet tooth. Something I must admit: I don’t really mind. While this bread can in fact be found in some corners of Ireland, it was historically made on very rare occasions. I make a mental note to perfect each of these versions during the cooler months of this year, but we decide to have Lynam teach us to bake brown soda bread for the time being.

He walks us through each step, lending a floured hand here and there, and within a few minutes we are seated comfortably at the table, watching the bread slowly rise inside the oven. We marvel at how quickly we went from sifting a few cups of flour, to rising bread. The time is passed by looking through old books of Lynam’s town, discussing his upbringing, and gaining a greater understanding of the tumultuous history of Ireland. “Soda bread isn’t actually Irish, you know. It came from America,” he explains. It was the indigenous peoples of the Americas who created the forerunner to baking soda by mixing maple or elm tree ash with a mild acid, like buttermilk—causing quick-breads to rise. The first soda bread recipe was published in 1796, nearly 50 years before baking soda was used in Ireland.

Soda bread’s place in Irish history began in the mid-1800s—in direct correlation with the Potato Famine. While the potato blight affected many countries, its effect on Ireland was absolutely devastating due to several factors. A disjointed government system, which long favored landowners with large estates, widened the gap between aristocrats and peasants. Tenant farmers and laborers who made up the majority of the population had very little land on which to survive, forcing them into dependence upon one single crop—potatoes. The variety that was most resilient, high-yielding, and calorically dense was the Irish Lumper, so all other varieties were abandoned for the sake of survival. Unlike other European countries, the Irish lacked the luxury of cultivating more than one variety, and when the blight hit, it destroyed the food supply for the majority of the island’s population.

It was in this climate the Irish turned to a food source that had been largely neglected—bread. Irish wheat did not do well with yeast, nor were homes equipped with ovens that offered a fixed temperature for baking—in walks quick-rising soda bread. A less finicky dough, it could be placed in a bastible, flat-bottomed cast iron pot, and suspended over open flames. Women began baking them en masse, utilizing relatively cheap baking soda in addition to a few ingredients every household contained: flour, salt and sour milk.

The bread required little time and effort, and it provided the necessary sustenance for large peasant families. Its increasing popularity among the poor, along with being made from soft wheat rather than hard wheat—a superior grain according to the British—made it an inferior bread. It became widely referred to as peasant food. A stark contrast from today, as it is greatly praised for its healthy properties and extolled as an Irish gem.

The Great Famine is a blight on the history of several countries and has forever changed relations between Ireland and England. Although America served as a beacon of hope, widespread ignorance of the horrors the Irish faced back home bred fear and disdain toward them upon their arrival on our shores. I hope our generation will be better and wiser than those who have gone before us. That we would embrace those that are seeking refuge, even now. Not only for their relief, but for the richness that we experience by leaning in and listening to the story of another over a shared table.

As we remove the bread from the oven, Lynam immediately flips it upside down, and we knock on it with our knuckles, laughing and listening for that hollow sound of baked perfection. As the bread cools, he prepares tea and we sift through more varieties of jam than you can imagine. Setting out the Kerrygold butter, he beams with pride that this treasure from his small country made its way across the Atlantic and beyond. We break into the craggy crust and he delights in a taste of home, while I savor a slice of nostalgia from a country I’ve come to love. “Not bad—for peasant food,” he teases playfully.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.