Writer’s Note: This is an abridged version of what happens during a seder meal, focusing primarily on food and drink involved and omitting many other key facets of a very detailed celebration. As I mention, it also chooses interpretations particular to the my own upbringing and does not necessarily represent a definitive view of the Passover seder and its many components.

——

Passover, or pesach in Hebrew, is one of the more well-known of the many Jewish holidays. It celebrates one of the most famous stories of the Old Testament, one that has been captured on film and in books, and even parodied on shows like The Simpsons. It is the tale of Moses, the Jewish people, and the Pharaoh of Egypt. It is the story of the 10 plagues that rained down upon the slave masters. It is the tale of a mighty God freeing his people after many years living in bondage, and it is the start of the book that eventually leads to Moses climbing Mt. Sinai, coming down with the Ten Commandments. It is a really, really good story.

And it is a story rooted in faith, culture and tradition. As a Jew, it is the tradition that makes this my favorite eight days of the year—a week in my life where my everyday life changes just a little bit, and reminds me where I come from. These traditions, even more so than with other holidays, are heavily rooted in food.

All Jewish holiday traditions involve food in some way. Each Friday night when celebrating Shabbat (the sabbath), we drink wine and share a loaf of challah (egg) bread. On Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year) we eat apples and honey. On Yom Kippur (the day of atonement) we fast. Judaism has a deep understanding of the role that food plays in our lives and makes great use of its power to help us think deeper about moments that might otherwise be unthoughtful. The traditions add a consciousness to the relatively mundane activity of eating dinner, forcing followers of these traditions to think about each bite that they take. Judaism makes special use of food to symbolize basic facets of the religion, the history of the Jewish people, and our individual morals and ideals. Passover, perhaps, does this the best.

In its most threadbare observance, Passover is a week when Jewish people give up bread, replacing it with large, bland crackers made simply of flour and water called matzah. This tradition of giving up leavened bread, and other bread-like products, like muffins and cakes and yes, even avocado toasts, stems from the notion that when the Jews of the Exodus were fleeing Egypt, they didn’t have time to let their dough rise, thus creating the original matzah.

In my own family’s home, my mother takes the Passover holiday as a moment to attack the entire house for a good spring cleaning. She works herself silly giving each nook and crevasse of the kitchen a deep scrub, making sure no crumb could possibly escape. She tackles the inside of the oven with steel wool, she washes the countertops with boiling water. She places our everyday dishes and silverware into storage, lines the cupboard shelves with butcher paper, and replaces everything with a completely different set of tableware that otherwise live in Tupperware boxes in the corner of the garage—the ones we only use for this one week each year, but feel familiar nonetheless. She tapes closed the kitchen pantry and moves perishables from the kitchen refrigerator to a second one in the garage, replacing the food that we normally nosh on thoughtlessly with new packages of items bearing the phrase “kosher for Passover.” When my sister and I were children, we’d even perform a ritualistic search of the house with a candle and a feather, looking for any last traces of bread that might have survived. My dad would hide slices of bread around our home for our hunt. It was silly, but it was a special reminder that this week was going to be a bit different.

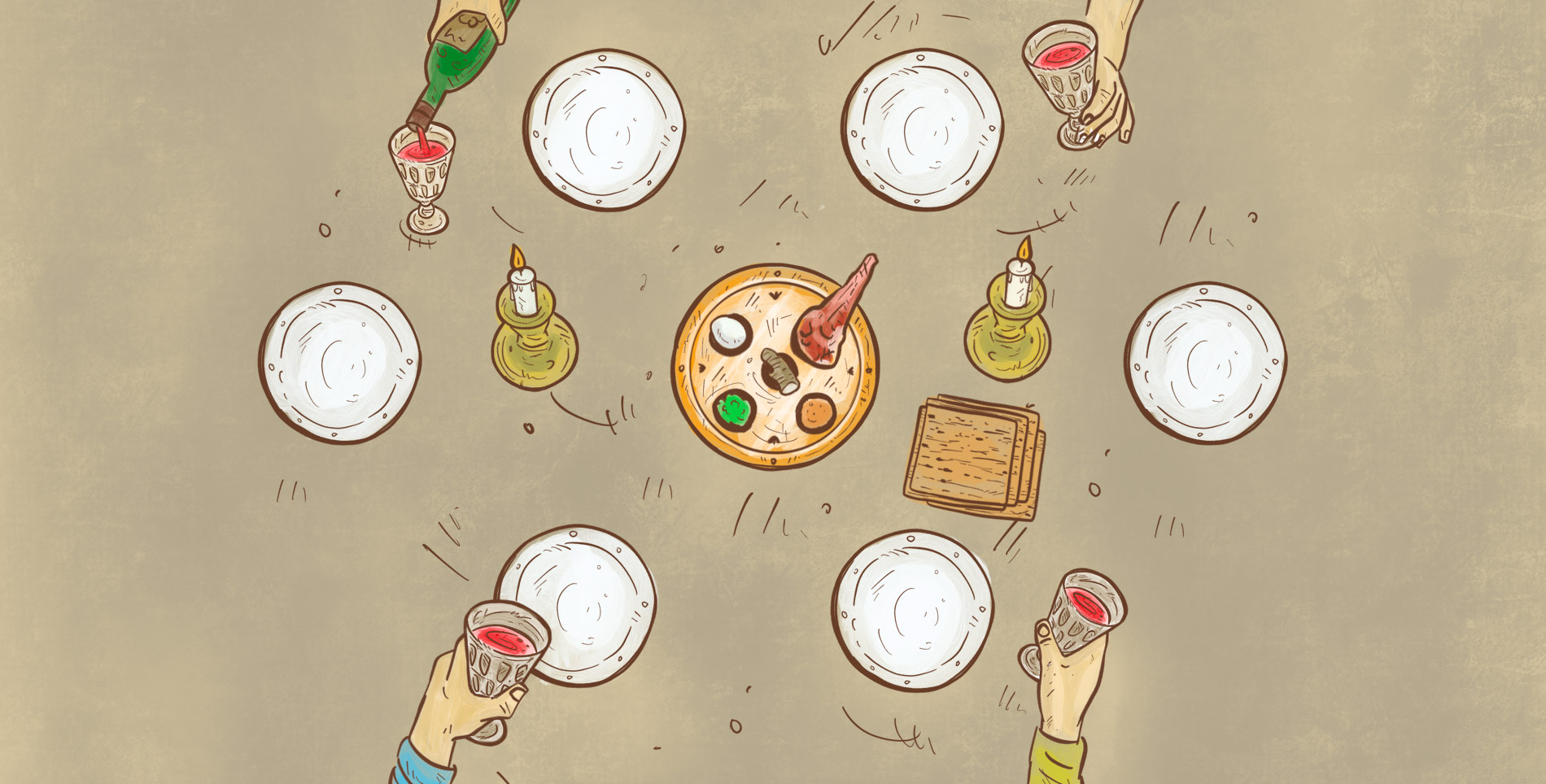

Once the household preparations are complete and grandma’s brisket recipe is slowly cooking in the oven, the week begins with a seder. This is the traditional Passover meal that families enjoy together. It is a formalized, ceremonious meal that includes a number of prayers, songs, and a telling of the Exodus story. The word seder actually translates to “order,” and refers to the order of 15 different rituals that must be done to properly celebrate. Of them, 11 include eating or drinking. The reason for such specificity to food during this observance is that everything on the table is representative—each bite intended to make us think. There is a special seder plate on which five (some say six) traditional foods are displayed, drawing the table’s focus to age-old symbolism—of life and freedom, of slavery and spring, of tears and sacrifice.

It must be understood that Judaism is a religion that leaves quite a bit up for personal interpretation and the Passover seder is no different. The order of things is the same around the world, but the foods can vary, as can interpretation of symbolism. But where we all can agree is that it begins with the first cup of wine. Four cups of wine will be consumed throughout the seder, and there are several explanations as to why; the most common answer is that they represent the four different ways God told the Jews of Egypt he would free them. Other theories refer to a dream the Pharaoh had or the four ancient world powers that had held Jews as slaves. Regardless, by the fourth glass of wine, most people come up with their own interpretation anyway.

Following the wine, the first bite of food arrives. It is called karpas, and while it is often dismissed as something simple, it is quite possibly the ultimate symbol for Jewish philosophy. Physically, karpas has been interpreted in several ways around the world, but is typically either parsley, celery, or a potato dipped in salt water, vinegar or lemon juice. My family has always used parsley and saltwater as a symbol of the greenness of the spring season muddled by the tears of the Jews who were slaves in Egypt all those years ago.

It is easy to see the simple symbolism and move on, but another very common Rabbinical explanation of karpas can be far more thought-provoking. In one wording or another, the answer to “Why are we dipping this vegetable into salty water?” is “Because we want you to ask that exact question.” The very first thing we eat during this large meal is literally meant just to stir conversation—to drive people into the story of why they are sitting around this table. It’s a simple taste intended to awaken and excite both the tongue and the mind.

It is important to begin the mental stimulation with karpas as the next item eaten is not until after the story of Passover, along with several other religious parables, have been told. That next item is, of course, matzah—the ultimate symbol of Passover, and the symbol of freedom. Typically there will be a stack of matzah on the table for sharing, but there are also three special pieces of matzah on the table along with myriad explanations for what each represents and rules for when each should be used within the seder meal. This is no ordinary cracker.

Next up, another part of the seder plate, is maror—a bitter herb. This is most typically presented either with horseradish or romaine lettuce—sometimes both. I’ve always preferred horseradish, as it makes its point much more forcefully. Like with most of these foods, there is no biblical definition of what this is meant to represent, but it is commonly said to embody the bitterness that slaves in Egypt must have felt in their daily lives. A walloping bite of horseradish burning within your sinus cavity is meant to produce just a moment reminiscent of that pain and frustration.

Continuing on is a rather unique moment in the 15 parts of the seder called korech. It is unique in that it is tied to a specific, extremely important and influential Jewish scholar named Hillel who lived over 2,000 years ago. It is told that Hillel would make a sandwich of matzah and maror and eat them together. A fascinating interpretation of this practice teaches that eating the unleavened bread, representing freedom, and the bitter herb, representing slavery, at the same time is the way that we need to think about all moments in life—connected. Slavery doesn’t exist without freedom and vice versa.

Another common practice when eating this “sandwich” is to dip it into charoset, yet another traditional dish that lives on the seder plate. It can be made in many ways, but is typically some variation of a chunky applesauce made with red wine and chopped nuts. It’s sweet and delicious, and makes a perfect balance to the heat of maror. Charoset is thought to represent the mortar that slaves in Egypt used each day when building stone towers for their masters.

At this point, two items remain on the seder plate. First, the egg, which symbolizes the beginnings of life as if the Jewish people had been born when they were freed. It can also be viewed as a statement that while the egg had been laid when the Jewish people were freed, it wouldn’t actually hatch until they received the Ten Commandments, teaching that both political and religious freedom are both needed to truly live (probably a bit more thought than given to your Sunday breakfast). Although the egg doesn’t play a role in the steps of the seder and doesn’t need to be consumed, it is quite tasty when dipped into the remaining salt water, with a bit of horseradish spread on top.

Finally, the shank bone—zeroa in Hebrew, which translates to “arm.” In addition to being an overt symbol for a sacrificial lamb, it can also be interpreted as God’s arm, outstretched, freeing the slaves. This is a bare, roasted bone, and the only item on the plate that cannot be consumed.

Having made our way through the entirety of the symbolic foods, it is time for dinner. Chicken soup with matzah balls, gefilte fish, brisket, chicken, vegetables, potato kugel—let the Jewish feast begin. Once completely full, a special piece of matzah is saved for dessert, along with a couple more glasses of wine. Fortunately the seder starts with that spark of thoughtfulness from the karpas, as the final moments of the night are a bit hazier, filled with the spirited (read: drunken) singing of Israeli folk songs, and a traditional toast to meeting next year in Jerusalem.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.