It’s early evening on a lesser-known island in the south of Italy, famous for its multi-colored marina, narrow streets and serene waters. While most tourists head to popular islands such as Capri and Ischia, Italians know Procida as the hidden gem of the Bay of Naples. I head out for a stroll around the eastern side of the island as the sun is setting and find the whole town abuzz. Everyone is out from hiding after the day’s intense heat, and the streets overflow with pedestrians, scooters and electric bicycles whizzing by.

Veering left, I branch off from the main drag––which consists of just two tiny grocery stores, a farmacia and two gelaterie—after all, what more could one need? With the shimmering ocean in view, I slowly drift forward, closing my eyes every so often to soak in the diverse sounds and scents of the island. A fragrance emanating from a nearby garden entices me, along with the older gent with an easy smile. He is taking advantage of the waning heat and dwindling light to harvest the ripened fruit. I offer a friendly “buonasera,” and a conversation ensues wherein he maintains that he’s no farmer; this is a labor of love. Row after row of lush, sprawling vines brimming with rich red tomatoes—all of this belongs to him. By the end of harvest season, he’ll have gathered over 50 kilograms to can for his children and grandchildren to enjoy all throughout the year.

A few days later I take to the streets once more, this time in the lamp-lit city of Caserta (35 miles north of Naples), in search of Campania’s famed buffalo mozzarella. A large stone building, set apart by its beautiful archway, captures my attention. The architecture screams 16th century, and I realize I’m amid the city’s historic Puccianiello district. Beneath the arch there are scores of crates––each full of tomatoes––being shuffled and stacked by a bustling group of young women and graying nonne (grandmothers). While curiosity is piqued, my appetite protests loudly––pleading for some local cuisine––so I stride onward toward a well-known trattoria.

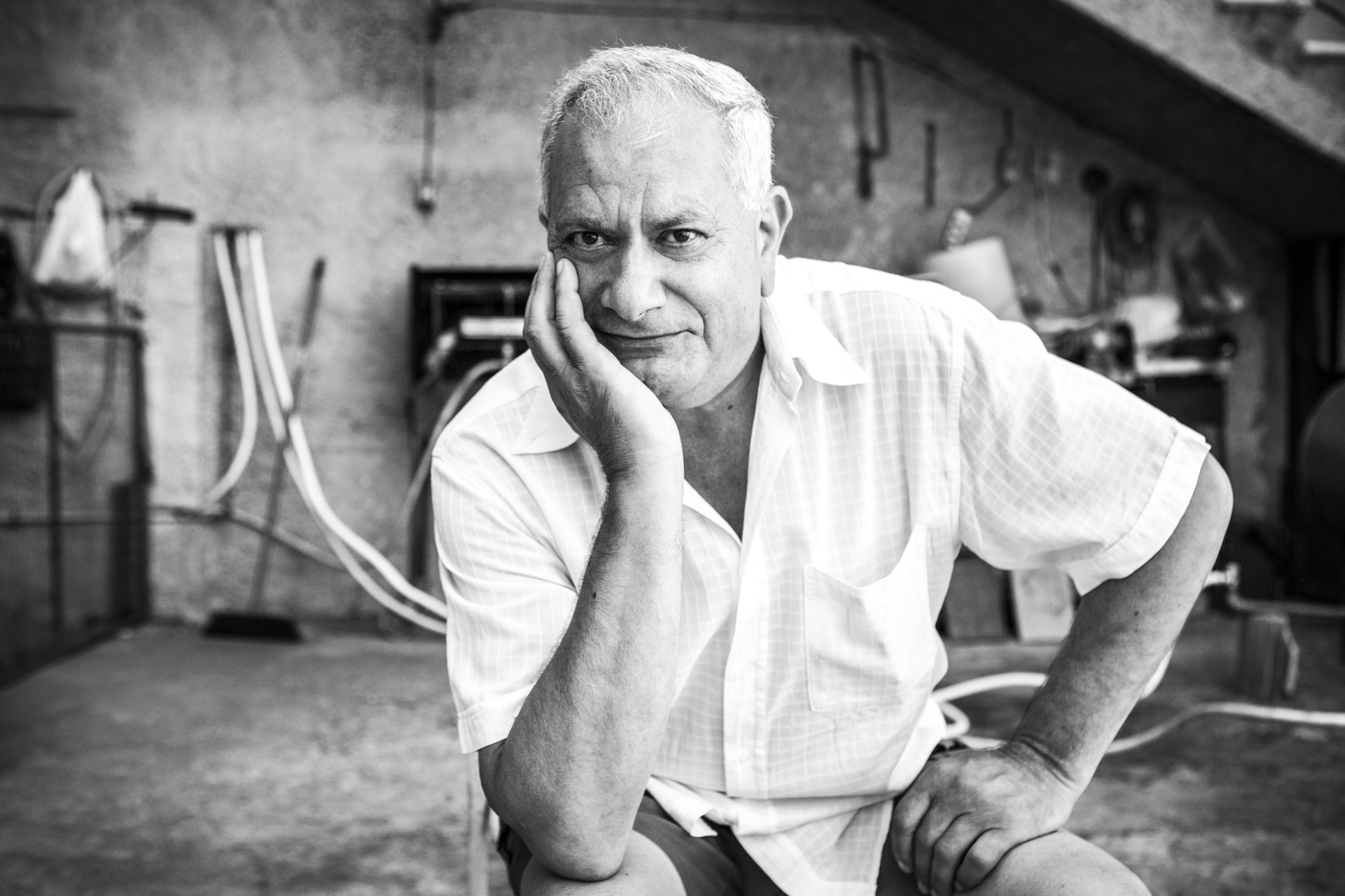

The following morning, meandering back from my daily ritual of a cappuccino and cornetta (pastry), I approach the large archway again and step inside as if beckoned by some irresistible force. There is a large courtyard encompassed by a gray, stone domicile two levels high, with several front doors leading into homes. Across the way, an older man stands peering into two large, steaming barrels, then bends down to adjust something. I offer a kind greeting, hoping to find favor with this stranger, but begin to feel uneasy as he approaches with deliberate steps, his face lacking the quintessential smile I’ve grown so accustomed to. He stops just short of me without saying a word and thrusts forth his hand, his stern face breaking into a grin as he utters a warm, “buongiorno.”

Unaware that I had been holding my breath, a sigh of relief escapes me as I explain that curiosity drew me within the walls of his home. With furrowed brow, I point to the steaming oil drums, and he leads me over, cautioning me to watch my step. I carefully avoid the tubes carrying fuel to the flames of this makeshift stove, and peek inside to find numerous bottles beneath the bubbling surface. Pepe Natale adjusts the heat with a tiny knob, ensuring that the water stays at a consistent rolling boil for the most important part of the canning process. He notes that when I had passed them the night before, they had just finished bringing in the harvest and were about to start the process of washing the tomatoes.

At this point, a woman comes out to see what’s going on, and Natale introduces her as his sister, Maddalena––Lena for short. She decides that her brother could use her assistance in walking me through the canning process and begins by clarifying that after the women wash all of the tomatoes, they’re thrown into a large metal vat and parboiled until the skins split. After waiting a few minutes for the tomatoes to cool, they’re removed from the water, and put through a mill which mashes them up, removing the skin and seeds. The vat, equipped with a spout, dispenses the purée into Peroni bottles.

Peroni, you ask? Yes, throughout the year, the whole household of Natale’s siblings and their families are charged with the responsibility of saving their empty beer bottles for this very occasion. The old caps are undoubtedly replaced with new ones, sealed with a manual bottle capper, and loaded into the barrels of water to boil for an hour.

Since the bottles are left in the drums to cool overnight, I return the following morning at 10 a.m. sharp to help Natale unload them. Exchanging smiles with his family members who are lounging in the courtyard, I prepare to wait a long while for this man who has spent all of his life on Italian time. At half-past, he arrives, and we begin putting the bottles of passata di pomodoro (tomato purée) into crates that will be distributed among the families of each of his eight siblings that reside there. Three generations are currently represented––all played a part in the tending, harvesting and canning of the tomatoes. And all will share in the fruit of their labor.

Impressed by the beauty of this intimate family, I ask Natale how long they have lived there. He replies the home is now his, but had formerly belonged to his father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and on and on he went. Desiring a more specific answer, I inquire as to just how many years his family has lived in this venerable home. His reply: “Sempre.”

It was remarkably profound how very real that word was to him and, what is more, how very foreign it seemed to me. Sure, it’s true that I can mentally acknowledge this notion of always—forever—but it isn’t based on any real understanding. Natale, however, is well-acquainted with this concept, for he has known it by experience. He has lived in it for five generations—this grand procession of those who have gone before him and those coming after. The entirety of his life has been spent within these four stone walls, with every August he has ever known marked by the tomato harvest.

This act of preserving pomodori is in itself an act of familial preservation: all members working together, maintaining deep relational bonds, preserving their most vital sustenance for the following year. On special occasions, the entire family will gather together in the courtyard—all contributing a few bottles each—and they will celebrate and feast as one. From seed to harvest, life to death, generation to generation, the cycle continues…sempre.

For the next year, while his wife works the dough making pasta by hand, Natale will stand in the kitchen beside her, open those bottles of passata di pomodoro and use them as the base for whatever sauce his heart desires. Among other ingredients, he will always add onion for flavor and basil for its ambrosial aroma.

As we say our final goodbyes, I express a heartfelt thank you to Natale and tell him of my deep love for Italy. With a beaming smile he spreads out his arms, reveling in the simplicity of it all and replies, “Questo è solo il mio modo di vivere.” This is just my way of life.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.