The Road From El Salvador To the American Restaurant

The journey of an undocumented immigrant from El Salvador, who rose to become sous chef of one of New York City’s top restaurants.

This story is published in The Reboot Issue of Life & Thyme Post, our quarterly printed newspaper for members. Get your copy.

David* is in his chef’s whites plating grilled octopus. He garnishes the marinated shellfish as if giving a caricia (caress) with twice-cooked crispy potatoes, cherry tomatoes, red onion, herbs, and a touch of sherry vinegar. He moves carefully and gracefully around the small, crowded New York City restaurant kitchen, issuing out a stream of orders to his team of prep cooks, sweeping up scraps, tasting next week’s specials, and never breaking a sweat.

He is thirty-four years old, the chef de cuisine of one of the West Village’s most popular restaurants, and an undocumented immigrant from Las Margaritas, El Salvador.

There are about 1.1 million Salvadoran immigrants in the United States. According to the Migration Policy Institute, Salvadorans are the country’s sixth largest immigrant group after Mexican, Filipino, Indian, Chinese, and Vietnamese immigrants.

“Being an illegal immigrant makes you hustle. I talk like a Brooklyn boy. I dress like a Brooklyn boy. I sound American,” David says. “If I hadn’t told you I was undocumented, you wouldn’t know.”

No one knows his parents scraped together $11,000 a piece for David and his younger brother to cross into the United States via Guetamala, paid to coyotes who attempted to rape his tía who accompanied the boys up until they boarded their flights.

Getting from El Salvador to the United States is more difficult now than ever, particularly as Mexico tightens its own borders from the rest of Central America and cracks down on migrants attempting to cross into the United States through the country. This policy has been given aggressive pressure from the Trump administration, which threatened to impose tariffs on Mexican goods in response to increased migrant arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border, according to Ariel Ruiz, a policy analyst from the Migration Policy Institute. Additionally, the Trump administration, citing the coronavirus threat to detention facilities, plans to send all undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers to Mexico.

David’s parents migrated to America from El Salvador without their children when he was four-years-old. “My parents knew if we stayed in El Salvador, my brother and I would either end up in a gang or fleeing gang violence the rest of our lives,” says David.

Many Salvadoreños are fleeing gang violence or the climate change crisis, according to Jocelyn Viterna, professor of sociology at Harvard University, who specializes in social mobilization amongst Latin America, particularly El Salvador. As a result of a U.S.-funded Salvadoran civil war over twelve years under the Reagan Administration in the 1980s, many Salvadoreños (mostly young men or boys with little education) fled the country to the United States in order to avoid forcible recruitment by guerillas. They arrived in America, most notably poor barrios in Los Angeles, and formed the infamous gang Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) or were recruited by its rival, Barrio 18 or simply 18 (Dieciocho).

These newly initiated Salvadoreños into U.S. gangs used violence for self-protection. Defensive violence turned into predatory violence and many were thrown into jail. They became even more violent in American prisons and were deported back to El Salvador.

Deportations meant the United States was shipping hardened criminals back to El Salvador. These deported gang members, with no money, education or family, formed gangs because all they knew how to do was be a gang member. Some of them didn’t even speak Spanish.

The climate crisis is due in part to the vulnerable natural geography of Central America, a narrow isthmus flanked by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, coupled with human deforestation and land degradation (deteriorating quality of functional soil for agricultural use due to overgrazing, over cultivating and more). El Salvador has seen a steady increase in storms, floods and droughts during the last thirty years.

Modern day Salvadoreños fleeing to the United States from gang violence or the climate crisis seek out established Salvadoran communities formed by those who fled during the war in the eighties.

In Las Margaritas, there are warehouse-like homes, open fields, functional but unfinished sewers, and half-built dirt roads. “A homey, small community,” David describes. “I remember when it rained, the streets flooded. My brother, cousin and I would swim in the streets.”

There was gang activity in his village, but his family was afforded protection since some of their relatives were members. But David’s parents—who arrived in the U.S. three years prior—hired coyotes to take care of smuggling him and his little brother to the United States via Guatemala. “My mom came to the United States in the false bottom of a truck, suffocating in the heat, toe-to-toe with other migrants,” says David.

His parents—who didn’t explain what was happening to a then seven-year-old David—took out loans and saved to muster up money from their earnings in the United States. His father was a cook at Tavern on the Green in New York City. His mother worked odd jobs.

David, his younger brother, and his tía took a long bus ride from Las Margaritas to Guatemala City, Guatemala. They slept in a hotel made out of clay with one bathroom shared by everyone on the floor. The doors were wooden with no locks. It was here that the coyotes tried raping David’s Tía Blanca and, David recalls, the “only reason they didn’t was because my brother and I were in the room.”

The coyotes brought them to a Guatemalan embassy to get their passports checked, and that’s when David realized they were flying under stolen identities. The passport photo showed a white boy with a white name.

“That’s why our trip to the U.S. cost so much,” David says. “We had doctored, fake IDs and flew instead of crossing through the desert or the river.”

At the airport, three of the other migrants they were with were detained and sent back to El Salvador. To get onboard to fly from the Guatemalan airport to the United States, David had to write his signature on a specific ID. But the written name didn’t match the signature on the ID and he was rejected. One coyote yelled and screamed at him. David was young and scared, but the next day, he attempted to sign the ID again. Success.

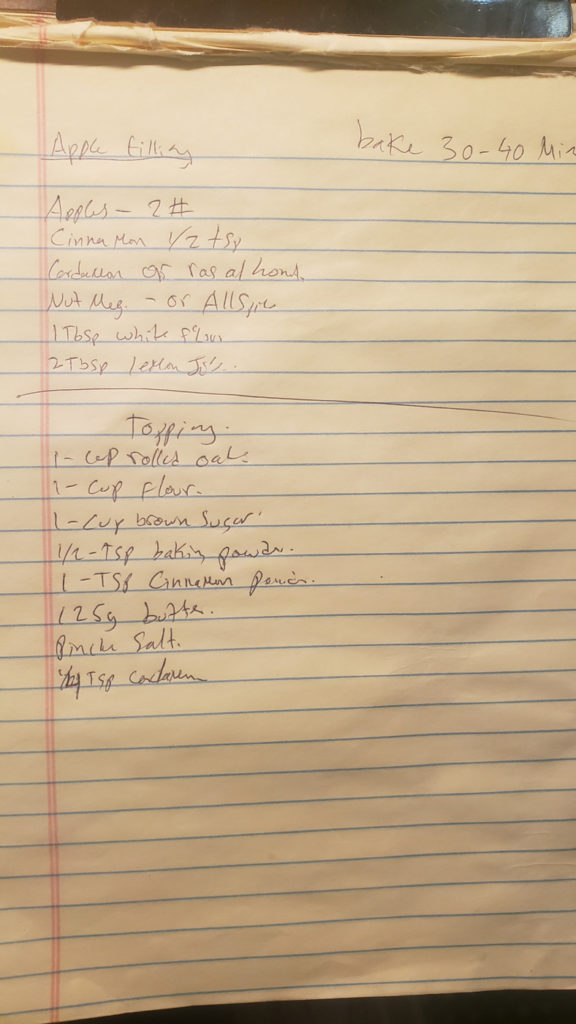

“That moment had a lot to do with my career. I’m a very prepared individual in the kitchen. I make detailed prep and ingredients lists, study how to prepare the dish step-by-step, and make sure my cooks have every single instruction written out. If I don’t do this, the flavors are wrong, we waste food, time and money,” David says.

“I think it was because I was traumatized from that moment at the airport when the coyote was yelling at me for not getting the signature just right on my documents,” he continues. “Because now the coyote is the customer. The coyote is the executive chef. And if I mess up, I get punished by them.”

“I got off of the plane from Guatemala and into Newark Liberty International Airport. I can hear my mom crying, but I can’t see her,” says David. “I’m tired, sleepy and hungry.” It was his first time flying. He was alone.

“The hardest part wasn’t getting here. The hardest part is staying here,” David explains.

After arriving in the United States, David was able to apply for Temporary Protected Status, or TPS. This particular status is afforded to nationals from some countries affected by armed conflict or natural disaster—as El Salvador was when the country was hit by two deadly earthquakes in 2001. Incoming Salvadoreños applied, and all those who were already living illegally in the United States having fled war and gang violence applied for it too.

Through TPS, David received a Social Security number, a worker’s permit, and a driver’s license.

___

A day in the life.

The following photos were taken by David in New York City (September 2020).

From the ages of seven to almost eighteen, David thought he was American, like everyone else. He lived in a house in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, went to a public school, made friends, and became intensely interested in computers and IT. And every time his TPS expired, the family lawyer reapplied.

But in high school, he got involved with kids who smoked weed and cut school. His grades dropped, and his mother didn’t know what to do with him.

“‘Don’t mess around or you will lose your TPS,’ she would say. But I didn’t understand what it meant to lose my TPS. I never knew what being an immigrant was because I grew up here. I hung out with all the white boys and white girls. Only later would I realize the consequences of my actions were exponentially greater because of my status,” David explains.

And when he got held back a year at school, his mother sent him to live with an uncle in Michigan.

David made new friends in Michigan. He worked printing labels at the meat factory where his uncle was under employ. Things seemed to improve. But one evening, he was pulled over by the police in a friend’s borrowed car that had warrants on it, unbeknownst to David. He had been dropping off another friend, who gave him a dime bag as a thank you for picking him up. And it was found by the police.

“Less than a gram of weed ruined my life. I got arrested that night. My TPS got taken away. It gave me a life sentence in the United States. I can’t leave. If I leave, I can’t come back,” says David.

He bikes everywhere since he can’t get a license; that requires a work permit. David hasn’t been able to work legally in the United States since he was eighteen; he is now thirty-four. He has been able to stay in the country because the immigration system is so clogged up. And his Social Security number is still tied to him. He uses it to pay taxes and receive tax returns.

After his arrest in Michigan, David returned to New York City to find a job that would hire an undocumented person. “There are so many of us here [in New York City]. It’s easier to hide, be accepted, and find work,” David says.

There’s always competition in the kitchen, says David, but Latinos and other undocumented folks never compete because of work status or country of origin. “You competed because you wanted to excel or advance in the kitchen for more money or a better title. And speaking English gave me an advantage,” says David. “I grew up in restaurant kitchens with Mexicans, Guatemalans, and other Salvadoreños. They are brothers to me.”

His first job was as a dishwasher at a now shuttered Austrian restaurant in Tribeca called Blaue Gans. The first few days were difficult; the chefs hazed him and got him drunk.

The food service industry is open and welcoming to undocumented workers. No questions are asked, generally speaking, about your work status, David explains, because the kitchen has jobs that no American wants to do.

“Restaurants need people who will work hard and not ask too many questions. We [undocumented workers] showed up, worked, and earned a paycheck. The only thing we cared about was how much we were going to make. Not benefits, breaks, vacations, or freebie office snacks,” David says.

“We take the jobs no one wants. I don’t see Americans lining up to wash dishes for eight hours, peel potatoes, or scrub pots and pans. I’ve seen maybe one to two white dishwashers total in my career,” says David. “Remember the Irish, Italian and Eastern European immigrants that came to America in the 1800s? They came to this country looking for a better life—the same thing we are trying to do now. History is taught, but it’s not remembered properly.”

“There is this notion that Salvadorans will get up at four in the morning and work fourteen-plus hour days,” says Professor Viterna. There’s a term for that, specific to Salvadorans, she explains: guanacos. It means “hard workers.”

Growing up, David’s father worked at Tavern on the Green. When he had to go to work but still look after David and his brother, they would help out by peeling potatoes and sneaking tastes of dishes like creamy lobster thermidor.

David has now worked at almost ninety-six restaurants. He dubs himself “an opener,” and his special talent is as a line jockey—a line jockey, or chef de tournant, is a jack-of-all-trades.

David worked his way through kitchens, ascending the ranks until he became chef de cuisine at one of the West Village’s most beloved restaurants. He manages a team of chefs and created lauded menu specials that are written about in magazines. Unlike most chefs, David doesn’t want the attention or praise. He wants to be a role model for other undocumented chefs and immigrants in the restaurant industry.

“My name doesn’t need to be anywhere public. I don’t need any of that. I just need a place to make money, feel comfortable, and not be afraid,” he says. “[My boss] has given me that. My priorities are not my ego. They are making money and creating a place where other immigrants don’t have to be afraid.”

He shares that with the increasing use of e-verify, web-based systems that allows enrolled employers to confirm the eligibility of their employees to work in the United States, it’s harder to get a job as an undocumented immigrant. So his goal is to ascend the brigade de cuisine so undocumented workers have a chance at working for him safely.

___

David wants to leave the United States in about five years. When COVID-19 struck New York City, David, along with thousands of other undocumented workers, were forgotten.

“I don’t want to be in a country that leaves us behind during a crisis,” he says. “We are dying and people are forgetting. I feel like I’m in jail.”

When New York City shut down, David was not able to apply for any federal or municipal relief. While some people were collecting an additional $600 dollars per week on top of unemployment, David didn’t have “the luxury of being unemployed.” He had to figure out how to survive on a total of $3,000 to his name for an indefinite period of time.

Fortunately, he had friends and a girlfriend who came to his aid. And when the executive chef and owner of the restaurant he works at set up a GoFundMe to assist the staff, David gave his portion to other workers who didn’t qualify for unemployment because he hadn’t yet revealed to his boss that he was undocumented.

He wants to go back to El Salvador and build a program for underprivileged kids to learn about personal finance, cooking, cleaning, organizing, and other “life lessons.” He envisions purchasing a plot of land, constructing a campus, and creating an attached restaurant. And over the next five years in the United States, he plans on saving as much as he can for the program.

*Name has been changed to protect the individual’s identity.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.