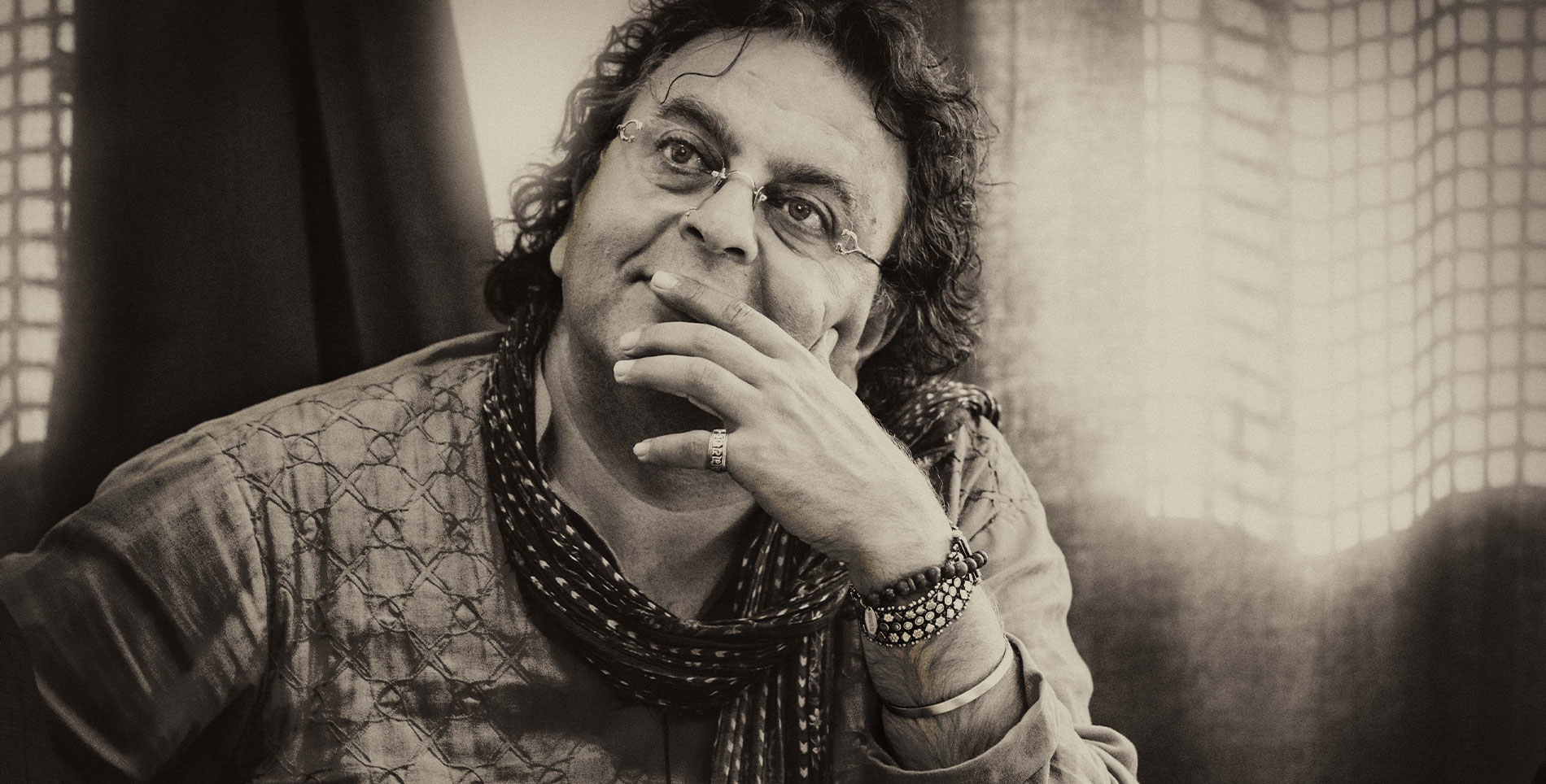

Above: Chef and Restaurateur Vikram Vij | Photo by Randall Epp

This story was originally published in The Reboot Issue of Life & Thyme Post, our printed newspaper shipping exclusively to Life & Thyme members. Get your copy.

When I first landed in Victoria, B.C., Canada, as an eager eighteen-year-old student, I was nostalgic for the food of my homeland, India. One of the first things I did was venture in search of the nearest restaurant that could feed me a steaming plate of biryani, and to my surprise, it seemed like every restaurant in a twenty-mile radius boasted “authentic East Indian cuisine.” As someone who hails from West Bengal (located in the eastern part of India), I was elated.

I soon learned, however, most of what I’d found was Indian in a broader sense, which consisted of biryani sans potato and butter chicken ostensibly flavored with ketchup. This was not what I’d expected to find under the “East Indian” marker.

In Canada, the cuisine of my home country is still referred to as East Indian, rather than just Indian, to specify its origins from the country of India, as well as to distinguish it from the cuisine of Indigenous people. Although laws and institutions pertaining to Indigenous populations still exist with “Indian” in them, the term has been deemed derogatory when referring to Indigenous people, and has fallen out of use since the 1970s.

This means that the need to specify cuisine from India as East Indian has become obsolete. There is no state or country called East India, and as Indigenous people are no longer called Indians, it follows that their cuisine would also not be labelled as Indian. But the phrase “East Indian” still remains in widespread use despite its misleading nature.

I wasn’t the only one baffled by the confusing nomenclature.

“I thought it meant food from the eastern part of India,” says Prasanth Babu Unnikrishnan, or “Bob” as he is affectionately known by customers at his South Indian speciality restaurant, Dosa Paragon, in Downtown Victoria.

“People here think Indian food means North Indian food. In North India, most foods are curry-based dishes, while in the South, there are more plant-based dishes,” he adds.

Bob and his wife Lathika have successfully introduced a facet of Indian cuisine that is nothing like what Canadians expect from a typical Indian restaurant.

Dosa Paragon first opened in August of 2019, and has become a fast favourite in Victoria. “In Victoria, there’s a growing vegan community, which has helped promote South Indian cuisine,” Bob says.

Nearly half of their menu features vegetarian or vegan dishes straight out of South Indian states, like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, that make unique use of lentils, steamed rice, and vegetables to create dishes unlike those found in typical plant-based restaurants across North America. In a city where more and more people are looking to eat less meat for a variety of reasons, the existence of Dosa Paragon means more culinary options for patrons—as well as a growing market demand for Bob and Lathika.

Unlike most Indian restaurants in the region, Dosa Paragon’s claim to fame is not tandoori chicken or tikka masala, but the flakey, crispy, lentil-based dosas and soft, spongy idlis reminiscent of South India.

Before opening his own restaurant, Bob worked at several eateries in Alberta and B.C., some of which served East Indian food. He confirmed that some restaurants would add ketchup to their curry-based dishes as a way to reduce both prices and spice levels for patrons unaccustomed to spicy food.

But when Bob opened his own restaurant, he found a new way to inspire Canadians who equate Indian cuisine with butter chicken to try his food: he and his wife created “butter chicken dosa,” in which they stuff butter chicken inside a dosa to introduce an element of familiarity to an otherwise new dish.

This gateway dish to South Indian food has resulted in hundreds of repeat customers who have gone on to try other traditional items on his menu.

Like most cuisines in Western countries, the popularization of dishes like butter chicken and naan is a consequence of Indian immigrants opening up restaurants to enable themselves to survive financially in a new country, but not to proliferate culture.

“We never ran the restaurants as a passion. We ran them as businesses. When you come as a new immigrant from another part of the world and you want to survive, you open up any business that makes money,” says Vikram Vij, a Vancouver-based restaurateur known for popularizing Indian cuisine in Western Canada.

“Every time I went to other Indian restaurants, it’s the same menu, same style, nothing has changed, and nobody is trying to bring awareness to the nuances of different parts of India,” he says, describing his experiences of Indian cuisine when he first moved to Canada.

Like most cuisines, the kind of Indian food popularized in Canada has largely been shaped by the diaspora’s main region of origin: Punjab. The majority of Indian immigrants in the country hailed from the northern state of Punjab and were some of the first South Asians to migrate to Canada at the start of the twentieth century.

As more and more immigrants brought the food of their homeland with them, Punjabi cuisine became the type of Indian food Canadians are most familiar with: rich, creamy curries, saag (or spinach) based chicken and paneer dishes, and the fluffy, chewy naan flatbread found in every Indian restaurant across the country. On the flip side, you’ll rarely encounter a Gujarati thepla or a Bengali luchi—flatbreads made out of different types of flour, hailing from the western-most and eastern-most states of India—at a restaurant in Canada.

Despite being decidedly one-note, many of these Indian restaurants serving up Punjabi cuisine strive to maintain authenticity. But as Bob and Vij’s testimonies reveal, the necessity to make a living in the restaurant industry means some immigrant-run businesses turn to disingenuous ingredients like ketchup as a way to increase profit margins.

Vij is an Indian-born chef who lived in several cities throughout India, like Amritsar, Delhi and Bombay, and studied French cooking techniques in Austria before moving to Canada in 1989. There, he opened three restaurants in Vancouver with his then-wife, Meeru Dhalwala.

The menu at one of their restaurants, My Shanti, shows how he brought distinct flavours from specific parts of India and created dishes that take diners all over the country, from Bombay to Calcutta.

“My Shanti is based on my travels [through] India, so if I went to somebody’s house and they made a delicious fish curry with mustard seeds and kalonji and panch phoron, that is represented in the menu,” Vij says.

They initially opened My Shanti with a menu full of dishes from Amritsar, Goa, Hyderabad—places North Americans most likely have never been to or heard of.

Vij takes issue with calling the cuisine East Indian due to its misleading nature and a lack of respect for the vast diversity of dishes originating in the Indian subcontinent—and by extension, a lack of respect for Indigenous cuisines in Canada.

“There is no country called East India, so to say ‘East Indian cuisine’ is wrong. It has nothing to do with the First Nations peoples,” he adds.

As we touched upon earlier, the term East Indian was derived out of a necessity to differentiate between cuisine from India and cuisine created by populations native to North America, back when Indigenous people were still called Indians in everyday parlance.

But born out of that mistake is a misnomer that exists to this day. The term “Indian” has since been cast out in Canada as racially charged, since it was originally used by Christopher Columbus after he landed in North America mistakenly believing he had circumnavigated the world and ended up in India. The historical connection between the country of India and North America’s native population ends there, with the mistakes of a colonizer.

The fact that we continue to use such antiquated terms is, according to Vij, an insult to both Indian and Indigenous cuisines and chefs. “Every other cuisine of the First Nations [people] should be given the same respect as where they’re from—whether they’re Metis, whether they’re Inuit, whether they’re from any other First Nation,” he says.

“We don’t call them Indian chefs,” Vij continues. “They’re called Indigenous chefs because that’s who they are, and they should be given that respect.”

Vij believes that the change in verbiage needs to come from within the restaurant industry, and shares an anecdote of how he affected a similar positive outcome many years ago.

Around the year 2000, Vij and Dhalwala won Best Ethnic Restaurant from Vancouver Magazine for Vij’s, one of their eateries located in Vancouver. Initially, the pair were honoured and quietly accepted the prize.

But a week later, having ruminated on the issue, they approached the magazine’s editor and asked him to dig a little deeper into his understanding of ethnic cuisine.

Restaurants from a broad range of Asian countries that offer wildly different cuisines were lumped into the same category, despite the fact that comparing a Japanese bento box to a Sri Lankan chicken curry dish is even more egregious than comparing apples to oranges.

“How can you say that Japanese food is the same as Indian or Chinese or Sri Lankan or Burmese? That’s just not right,” says Vij.

In contrast to the grouping of hundreds of cuisines into one “Asian” or “ethnic” category, you’ll almost never encounter a similar grouping of European food in North America—rather, dishes from different European countries are given their due respect, generally with a nod to their country of origin.

But the magazine in question took Vij’s criticism in stride. The next year, they changed their categories from Best Ethnic or Best Asian restaurants and further divided them into Best Indian, Best Malaysian, and other awards for which countries of origin were specified.

“It took somebody like us to take a stand. They did listen, but they can only listen if we stand up for ourselves. Now I think the time has come to not say ‘East Indian’ cuisine. It should be ‘Indian’ cuisine, because that’s where we’re from,” Vij says.

As for Indian chefs trying to introduce foods from different parts of the country throughout Canada, Vij says they still have their work cut out for them. Until recent years, he says, not many Canadians were willing to try dishes outside their comfort zone.

“We’ve broken it down because people have traveled a lot, and people need to still travel more, but now we’ve got COVID-19,” Vij says. “People who are older now are not going to go to India because of the pandemic, and [for] the new generation of travelers, it’ll be another two or three years before they can even afford to go to India.”

The restaurant industry around the world suffered a particularly daunting blow when the COVID-19 pandemic forced a shutdown of dine-in services, but recent statistics show signs of recovery. Data from Statistics Canada indicates that while restaurant industry revenues dropped by over $3 million per month between February and April in Canada, the sector had begun to recover by June.

For eateries offering innovative dishes from different parts of the world, prolonged global travel restrictions may mean their businesses serve up global experiences on a platter. While a vacation in India may not be in the cards for many months (and maybe years), a hot plate of masala dosa or some cool idlis can take your palate on a trip straight to Kerala.

Vij believes if there are chefs passionate enough to brave long hours to bring dishes from Bengal or Gujarat to the table, Canadians will be lining up to try the food.

Over at Dosa Paragon, Bob and Lathika offer proof. After just one year of operation, Bob says around seventy percent of their patrons are repeat customers—a figure that isn’t difficult to believe for those who have tasted the cuisine.

Today, after months of pandemic-induced shut-downs and a dearth of tourists, Dosa Paragon still has a steady stream of take-out orders flowing out of their kitchen, fuelled by locals who just can’t get enough.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.