The Women Responsible for Italian Rice—and Workers’ Rights

The legacy of Italy’s mondine—the women who historically weeded the country’s many rice fields—is agricultural, cultural, culinary, and above all, political.

Editor’s Note: This story is published in The Legacy Issue of Life & Thyme Post, our exclusive newspaper for Life & Thyme members. Get your copy.

Grasp at the root of the Italian word mondina and you will discover the verb mondare, which (in certain contexts) means to weed. From this, it is easy to understand the work of the mondina, a woman employed to weed Italy’s rice fields during the 40-day period of summer known as the monda. Without her, unwanted plants would compete with cultivated rice plants for water, soil and sun, resulting in a reduction in crop production—in other words, there would be less food.

A true definition of mondina, however, cannot be summed up in a short-term job description. To be a mondina is a lifelong identity with a legacy that ripples outward across the centuries like the water around their calves while wading through the rice paddies, broadly impacting Italian agriculture, culture, cuisine and politics.

“Rice weeding in Italy has been an almost entirely female agricultural workforce pretty much from the start,” says Dr. Diana Garvin, author of Feeding Fascism: The Politics of Women’s Food Work, who has extensively researched the history of mondine.

Rice cultivation first took place on the Italian peninsula around six hundred years ago, and rice weeding was done entirely by hand until the 1960s when modern agricultural practices and machines outpaced mondine. Garvin notes, in the decades leading up to the end of the mondine era, up to “95% of all weeders were women” (the supposed justification being that they were better suited than men to this kind of “methodical, patient detail work”).

“A lot of the mondine were so young when they started. I think the legal age was 15, but people would lie about their age to sign up earlier,” says Garvin, citing financial hardship as the motivation. “They would often follow their mothers into the fields, so you could have three generations [weeding] at once.”

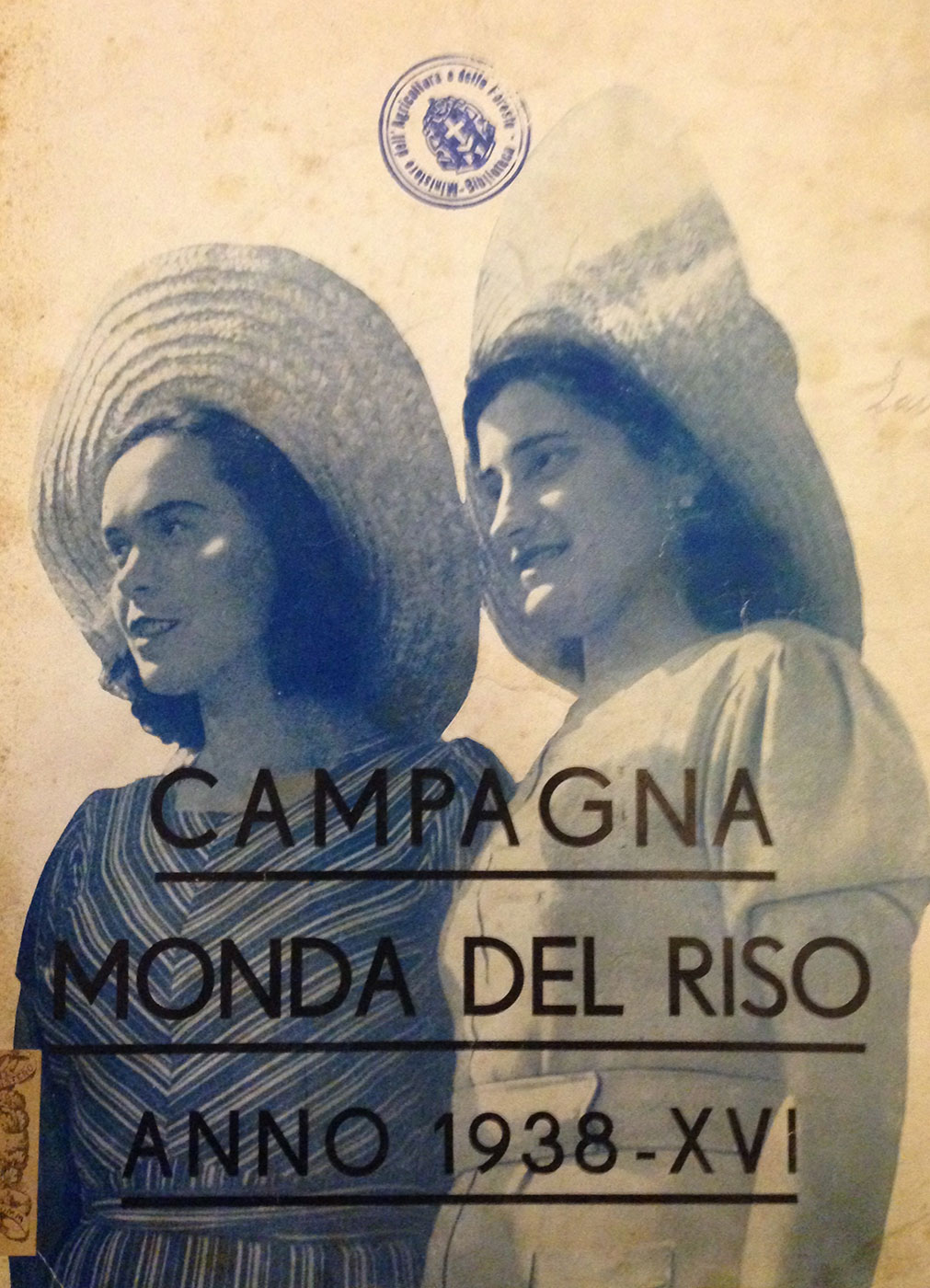

“Mondine would be from some of the toughest parts of the working class—the work was so physically difficult, there was no way you’d sign on for this unless you absolutely had to,” Garvin explains. “Some lived close to the rice paddies and would commute by bike, but the vast majority were from small towns in Northern and Central Italy—Emilia-Romagna, Piedmont and Lombardy—and they were traveling in the cattle cars of trains. It was a really visually striking event because everyone would show up with those big signature straw hats that were meant to protect them from the glare bouncing off the water because they were working bent over for hours.”

This event was immortalized in the film Riso Amaro (Bitter Rice), which appeared in cinemas throughout Europe in 1949 and is considered a classic of Italian neorealism. Filmed on location at a rice farm in Northern Italy, actual mondine can be seen working in the background of some of the movie’s most iconic scenes.

As a result of the film’s popularity, most Italians still have at least a passing knowledge of some mondine stereotypes, like the women being politically progressive. Garvin explains that this aspect features prominently in Riso Amaro because it addresses the “fears and fantasies” around the question: “If you had a big group of women on their own, what would they do?” In this way, the film captures a “really rare moment” for women of this era to gather “outside the context of the parish or schools or families.”

These women did not waste the moment. Often in the absence of men, while weeding land owned by men unwilling to undergo the discomfort of this work, mondine talked and, most importantly, they sang. Garvin refers to their songs as a source of “political education” in which information about current affairs could be shared and opinions voiced.

“In interviews with a lot of former mondine, they credit their time in the rice paddies as really formative of their political consciousness,” says Garvin. Whether they worked for just one season or many, the experience motivated mondine to take action, bolstered by a sense of awareness and community that would not have been fostered elsewhere at the time.

According to Garvin, there is a “near-constant state of revolt on the rice paddies, where they’re singing anti-fascist songs,” but their political activism was not contained to the farms where they worked. “Some of the really successful mondine strikes focused on bringing the railway station to a halt until better working conditions were met. Things like the eight-hour workday, the amount of pay, and reproductive healthcare—including being allowed to bring infants to the paddies to nurse.”

Women in Italy “didn’t have the vote until the mid-1940s,” as Garvin points out, but in the decades prior, many mondine would “attend political meetings alongside their husbands or brothers,” bringing a female perspective to a space from which they were typically excluded. She adds that mondine also had “a higher degree of power in their families than was typical for the period.”

“A hard and fast rule of power is that if you have cash, you’re setting the ground rules,” explains Garvin. Mondine received part of their payment in the form of rice, but they also received some cash. “Most folks were living more in a barter system, so it was often that mondine would generate the only liquid capital for their families.” Since men tended to receive payment in the form of goods, rather than money, “women had a larger say in what was going on at home.”

Although Italian culture continued to be governed by conservative, patriarchal values, necessity dictated that a woman’s place was in fact not limited to the home, especially during the mid-20th century when the first and second World Wars led to issues of food insecurity and labor shortages.

“All the way back to Ancient Rome, Italy could never produce enough grain to support its pasta habit. It’s always been a grain importer,” Garvin says. The challenges of sourcing wheat from other countries increased in the wake of World War I, and the fascist regime, led by Benito Mussolini, did not want to depend on foreign trade partners. For this reason, the Italian government began to strongly advocate for a system of autarky in which Italy would be totally self-sufficient as a nation. Mussolini sought to “ramp up production and consumption of only Italian foods and Italian products.”

For a country devoted to pasta produced with wheat grown elsewhere, this presented a need to find another grain that would fill Italian fields and stomachs. This struggle, known as the Battle for Grain, came to be a defining characteristic of the ventennio fascista (the roughly 20 years of the fascist government’s rule of Italy, beginning in 1922). The regime’s solution, as Garvin puts it, was to “celebrate rice as a patriotic dish.”

It turns out that what was even harder than convincing Italians to give up pasta in favor of rice was convincing the mondine to play the role of good patriots.

“The regime so desperately wanted these women to like them and they just absolutely despised the fascists,” says Garvin. “[Mondine] were one of the earliest groups that identified with the left and the regime was utterly dependent on them.”

While the government was printing pro-rice propaganda and publicly lauding the work of mondine, the women were chanting songs in the paddies that disparaged fascism and rice. Fascism was uprooted from Italian soil by the end of World War II, but rice dug in deeper, more so due to the mondine’s labor in the fields than their cooking in the kitchen.

“You would think, given that they’re working in the rice fields, you’d see a lot of recipes coming [from mondine],” says Garvin. This was not the case, primarily because mondine had too much rice and not enough of anything else.

Butter, cheese and other flavorful ingredients used in classic Italian dishes were largely inaccessible due to wartime privations and financial constraints. Even the rice they were given was often poor quality. “The women talk of not knowing whether they should eat the rice in their bowl or weed it because it’s already sprouted,” Garvin says.

Mondine ate rice daily during the weeding season, as it was often the main source of sustenance provided by their employers. To add flavor to this monotonous diet, mondine often engaged in what Garvin calls “light acts of civil disobedience,” including foraging and food theft.

“If they came across wild bird eggs in the fields, they’d drink those raw. If they found frogs, they’d boil them,” says Garvin. Mondine, however, generally did not steal directly from the landowners’ personal food supplies, which were outside the realm of informal ownership they felt in the fields that thrived because of their exertions.

This sense of justice is one of the defining characteristics of mondine and is the reason for which their contribution to Italian history is not just agricultural and culinary, but also fundamental to the development of modern Italian culture and politics.

Today, Italy is the top rice producer in all of Europe. It is both because of and in spite of the mondine that rice remains a key ingredient in Italian cuisine. But more so than in a bowl of risotto, their legacy lives on in every Italian woman—whether she’s taking a seat at the dining table or a seat in parliament.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.