Oct. 18, 2019

The Hyphenated American Food Staples

American foodways are a fluid representation of immigrant cuisines, adapted and integrated to become new cultural hallmarks.

Words by Ariel Knoebel

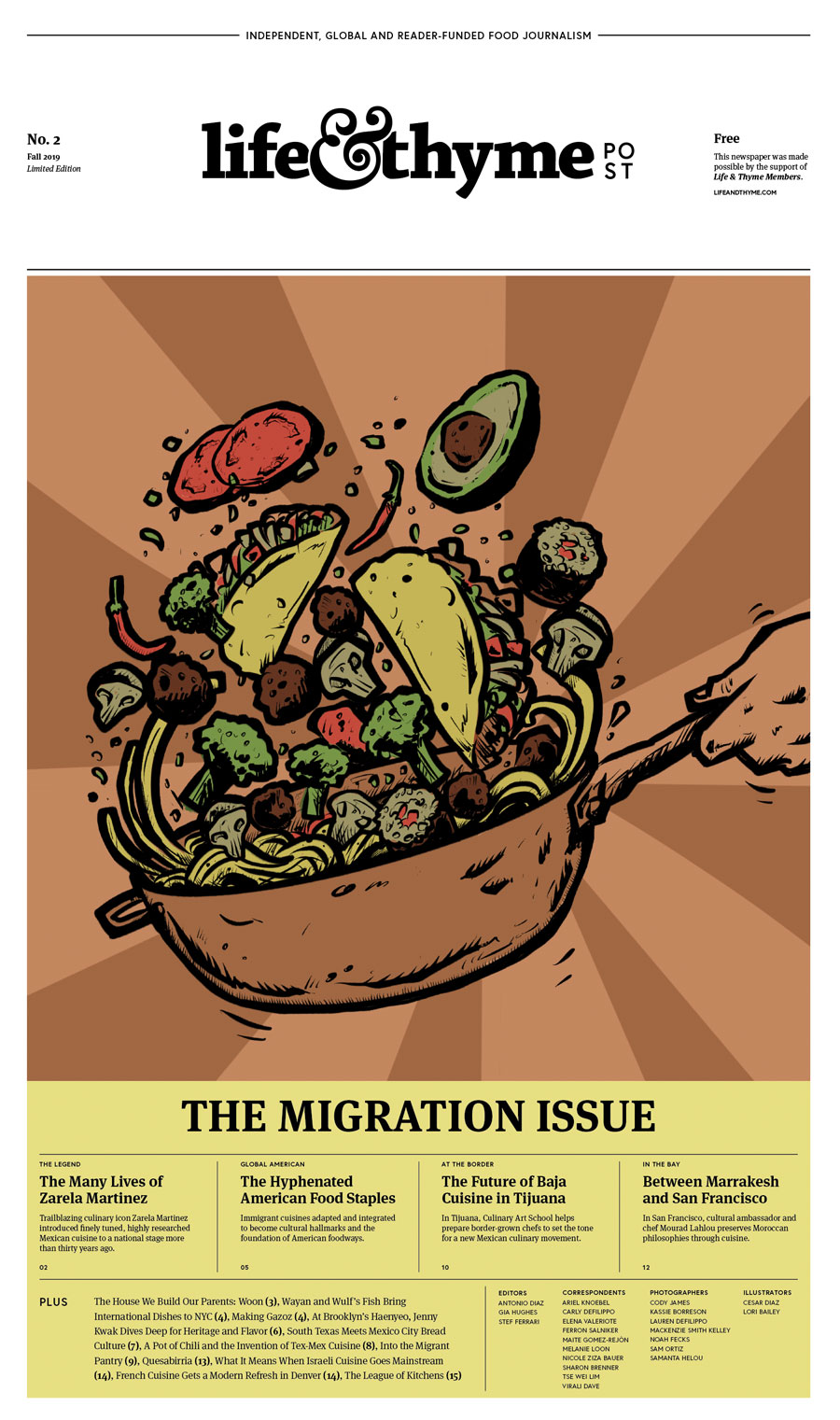

Illustrations by Cesar Diaz

This story can also be found in The Migration Issue of Life & Thyme Post, our limited edition newspaper for Life & Thyme members.

The menu at Sichuan Garden in Brookline, Massachusetts, is likely familiar to anyone how has ordered Chinese food in the United States. Red Chinese characters precede the English names of each dish. Chili peppers in the margins denote spicy dishes, warning diners to protect their palates. And after pages filled with items like Chengdu duck stew and tiger skinned pepper comes the section titled “American Comfort Entrées.” That’s where I find dishes I’ve grown used to in my decades of ordering egg rolls—the General Tso’s chicken, the beef and broccoli. Chinese restaurants outnumber the top three fast food chains in America combined, and yet it is the back half of this menu many Americans think of as Chinese food, starkly juxtaposed from the clearly marked “Authentic Cuisine” up front.

“You will notice a lot has changed. The menu is focused more on traditional recipes—recipes my mother prepared for us while I was growing up. But don’t worry, all of the American comfort dishes our community has grown to love are still here,” owner Ran Duan writes in his introduction to the newly designed menu of his parent’s twenty-year-old restaurant when he took over and revamped the concept of the neighborhood fixture last year. “The American Dream is used in many ways,” the introduction continues. “It is essentially an ideal that suggests anyone coming to or in the U.S. can succeed through hard work with the potential of leading a happy and successful life.” Not only did he change up the menu, he added a sleek marble-topped cocktail bar where hip young bartenders mix $14 tiki cocktails for a much different local clientele than those who visit for the Fei Teng fish stew that tastes just like home, real or imagined.

The experience of dining at the restaurant’s Blossom Bar is an exploration of the complicated concept of culinary authenticity. In taking over from his immigrant parents, Duan added more authentically Chinese dishes to the menu, in addition to the typical “Americanized” Chinese food. He also redesigned the space to feel more like a hip Miami hotel than a Boston Chinese restaurant, and tucked a world-class cocktail program into the corner. It is a perfectly American establishment—born from the culture of a far away place, ever-evolving to meet the whims of its immediate community, and building a set of unique tastes and traditions of its own.

Chinese food was the first commodified ethnic food in America, originally brought here by laborers working for the railroads during the Gold Rush. Chinese food in America today represents a history of invention, resourcefulness and cross-cultural inspiration. The iconic fortune cookie, originally from Japan, was popularized in San Francisco’s Chinatown during World War II. Famously, General Tso’s chicken illustrates the confusing cross-cultural history of Chinese-American food. The dish was originally created in the Hunan province, but the saucy fried chicken nuggets from your local take-out joint bear little resemblance to the original. The dish was sweetened and the chicken bones and skin were removed and replaced with a crispy shell, all to fit the American palate.

“[General Tso] has marched very far indeed, because he is sweet, he is fried, and he is chicken,” says Jennifer 8. Lee in her 2008 TED talk. “All things that Americans love.” Lee travelled across the world looking for the origin of General Tso’s chicken, and discovered the dish is far more foriegn in China than in America. Broccoli, a staple of the dish, was borrowed by Chinese-Americans from their Italian immigrant counterparts, when more traditional Chinese vegetables weren’t available in American supermarkets. Lee did, however, visit the hometown of the historical namesake of the dish. “General Tso is a lot like Colonel Sanders in America, in that he’s known for chicken and not war. But in China, this guy’s actually known for war and not chicken,” she says. The Chinese people she showed the famous dish to during her travels across the country had no idea what it was.

Food helps us understand who we are and who we aspire to be. For immigrant communities and so many who wrestle with their desire to become American and their deeply held ties to their homeland and culture, food can be both a source of comfort and a battleground for warring cultural identities, prejudices and values. Many immigrant-American foodways have evolved along a similar path: displaced citizens found themselves in a new country with little or no access to the ingredients necessary to make their favorite dishes. They dug through unfamiliar American supermarkets to find alternatives, swapping fresh rice noodles for thick dried pasta, homegrown eggplant and backyard tomatoes for chicken cutlets and canned sauce, or ground beef and orange cheese in place of queso fresco and barbacoa, and created new culinary lexicons blending their heritage with the distinct regional flavor of their new home. So often considered inauthentic or watered down, these dishes tell the stories of changing cultures, rich historical transitions, and exemplary American ingenuity.

While exploring the hybrid cuisines, it’s important to understand what makes food American in the first place. American history professor Donna R. Gabaccia writes in her book, We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans, “Americans have no single national cuisine. But we do have a common culinary culture… We are multi-ethnic eaters.” The American diet evolved regionally, with no collective identity around American food culture. The puritanical influences in New England dining contrast with the spiced Creole cuisine of the Southeastern U.S., which bears little resemblance to the Tejano traditions of the expanding American West and the much more recent creation of California cuisine.

Immigrant-American cuisines have become culinary traditions in their own right with rich histories and important contributions to the patchwork identity of American cuisine. These foodways emerge as a reminder of home for often isolated communities in an imposing country.

Today, one in eight American restaurants serve Italian food. However, in the 1930s it was considered an exotic culinary experience to go to an Italian restaurant. Bohemian explorers in New York City would venture to dine Italian for the experience of immigrant hospitality. Italian-American immigrants in the early twentieth century who arrived from poor regions of Southern Italy brought with them their peasant cuisine, which was heavy on grains, light on proteins, and primarily based on homegrown produce and subsistence farming.

For decades, this kept the Italian community segregated, until it became increasingly difficult to rely on backyard gardens and homemade wine, and these immigrant communities began to shop in the grocery store alongside everyone else. They began to replace homegrown tomatoes with canned sauce, and gained access to more affordable proteins. Thus, American-Italian food, with fist-sized meatballs in slightly sweet tomato sauce and pasta studded with large hunks of protein emerged. Sunday supper became a far cry from the light, vegetable based meals of the homeland, and Italian food entered the regular rotation of American weeknight meals.

While Italian food developed into an American staple, Mexican is arguably the most inherently American of immigrant cuisines due to its pervasive presence across the country and countless regional variations—and it’s also potentially the most contested. While there are distinct regional variations of Mexican-American food across the nation, especially the Southwest, many people use the wide umbrella “Tex-Mex” to cover Mexican-American food. Referring to the marriage of traditional Mexican foodways with that of the Tejas region of the U.S. (most of which was, at one time, Mexican) was popularized by cookbook author Diana Kennedy in the 1970s. She used it as a pejorative term, describing the typical plate in her cookbook The Cuisines of Mexico as, “an overly large platter of mixed messes, smothered with shrill tomato sauce, sour cream, and grated yellow cheese preceded by a dish of mouth searing sauce and greasy deep-fried chips. These do represent some of the basic foods of Mexico—in name only—they have been brought down to their lowest common denominator.” Despite Kennedy and her contemporaries’ violent rejection of Tex-Mex, it has become a prevailing prototype of Mexican food in America today.

As with many immigrant cuisines, Mexican-American food, and Tex-Mex specifically, emerged from necessity as the region transformed from Mexican to American, and new ingredients such as wheat, beef and cheddar cheese made their way into Tejano pantries. Since then, influences have spread across the country with the Mexican diaspora, sparking regional variations from Baja-style fish tacos, to jumbo flour tortillas in the Midwest, to green chile sauce in New Mexico, and Korean barbecue tacos amidst more traditional styles in Southern California. “It’s not surprising, in every region, you have your own historical strain of Mexican Americans, just like in Mexico, the foods kind of develop in each area of the United States depending on what the population and what the population can historically work with,” Arellano explains.

The taco is at once indicatively Mexican and inarguably American. “The taco is right up there with hot dogs and apple pie,” asserts NPR’s Carolina Miranda in a program titled The California Taco Trail: “How Mexican Food Conquered America.” There are countless variations, from the aforementioned Asian fusion variations sold for $4 each at food trucks in L.A., to the hard-shell assembly line creations at Taco Bell, to Austin breakfast tacos that can send displaced Texans into a spiral of homesickness. Each distinctive style, born from the blank canvas of a tortilla shell, tells the story of different community’s search for identity in America. Arellano, when asked about his favorite tacos in Los Angeles, listed Cielito Lindo on Olvera Street as one. “Those are tacos that have been sold with the recipe unchanged since the 1930s. A lot of people would say those are not real, authentic Mexican food. But you know what? Tell that to the Mexican who brought them across the border in the 1930s. Tell that to the family that’s still selling what’s been their grandma’s recipe for eighty-seven years. That’s about as authentic as you can get in L.A. It’s as authentically L.A. and as authentically Mexican immigrant as you’ll find anywhere.”

These dishes, have come to define the American culinary landscape. By bringing their own culinary traditions to their new homeland, and then practicing characteristic American ingenuity and evolving traditional foodways to meet the needs and fit the limits of their situation, immigrants have created signature American cuisine. Gabbacia writes, “to abandon immigrant food traditions for the foods of Americans was to abandon community, family and religion, at least in the minds of many immigrants.” Instead, they blended these to create a new kind of food tradition all together.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.