October 29, 2019

Daniel Humm’s Personal Touch

In New York City, Chef Daniel Humm finds inspiration for his globally renowned restaurant, Eleven Madison Park, through various creative media as well as personal friendships, like the one he shares with artist Rita Ackermann.

Words by Stef Ferrari

Photography by Noah Fecks

“…the Swiss are like coconuts. It’s not because they are small and hairy and you want to throw things at them. Rather, it’s hard to break through their outer shell and into their private sphere. But once you do, you have a friend for life.”

This is an observation by the British writer Thomas Stephens regarding the Swiss culture of friendship. Daniel Humm, the Swiss-born chef and owner of one of the most celebrated restaurants on earth, New York City’s Eleven Madison Park, has been written about—a lot. Finding something original to say—about his life, his food, his philosophy, his origin story—is a daunting task for a journalist.

It’s a little like trying to crack into a coconut.

I’ve interviewed dozens of chefs over the years, many Michelin-starred, “celebrity,” and stars of both kitchen and screen; and in that time, quite a lot has changed. Increasingly, we’ve seen barriers go up between the media and the kitchen. Where we once were able to pop into a restaurant sometime between service and have a conversation candidly, now we must arrange meetings and coordinate schedules with managers and publicists. Canned responses are issued from the mouths of subjects, and you never know if you’re getting the real story or the one that has been approved by a team of reps.

Chefs that came up during Humm’s day didn’t necessarily pursue fame, because for their generation, it really wasn’t a thing. Instead, they went after accolades and industry renown—perhaps just a place to carve out their own style and get creative with their cuisine. While that attention and adoration has many perks, there’s something to be said about the loneliness that comes with celebrity and notoriety. Such is true of any figure in the public space, of course, but given the intimate nature of the hospitality world, it seems especially unfortunate to have so much of the conversation sterilized, systematized, and scaled to every publication on the planet.

With that in mind, I’m not entirely sure what to expect when I meet Humm. It’s technically springtime, but still quite cold where I wait on a Williamsburg street. I’m scheduled to meet the chef and his close friend, the artist Rita Ackermann—who is equally formidable in her own industry. In the interest of getting to know Humm in a context outside the kitchen, I had requested we have a conversation outside the restaurant, to get a sense of how the chef draws inspiration in his own life. Visiting Ackermann’s studio was his suggestion.

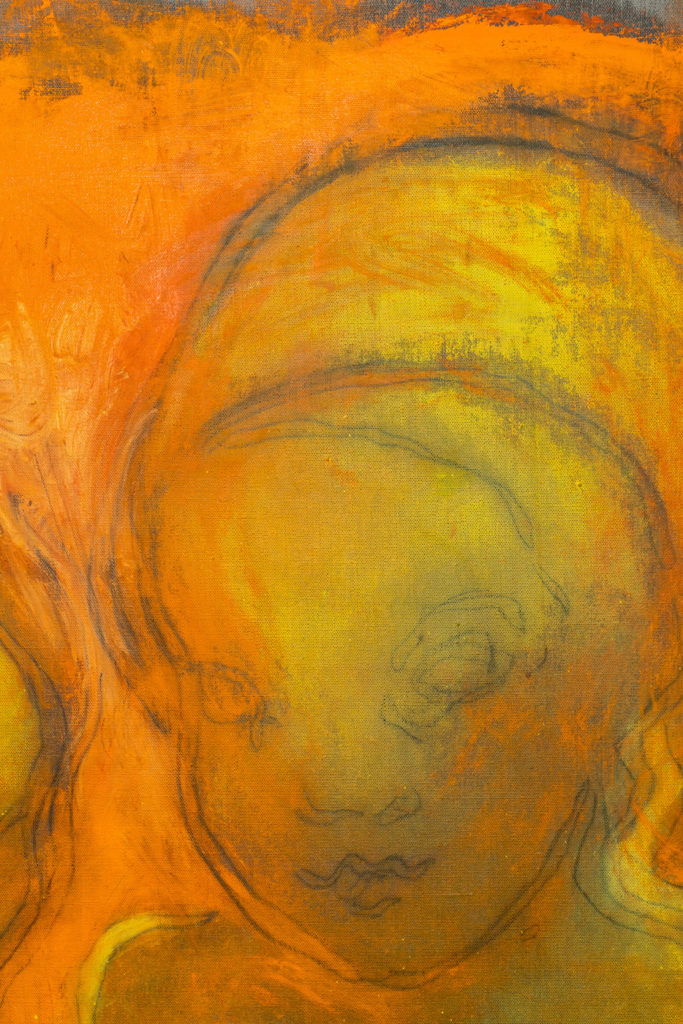

I was very familiar with Humm’s resume, but as a fine art neophyte, I felt it necessary to research Ackermann’s. Rizzoli, the publishing house which released a book of her work in 2011, described her pieces as exploring “the paradoxical relationship between fragility and violence, as she derives inspiration from literature, film, philosophy, and popular culture,” through “a new visual language: paintings, drawings, and collages which telescoped between a virtuoso—and sometimes brutalistic—expressionism and taut, precise figurative drawing.” I was reminded of some of the evaluations of Humm’s own work, which has often been compared to fine art, abstract, beyond the average food sphere—a new culinary language, or at least his own very unique voice.

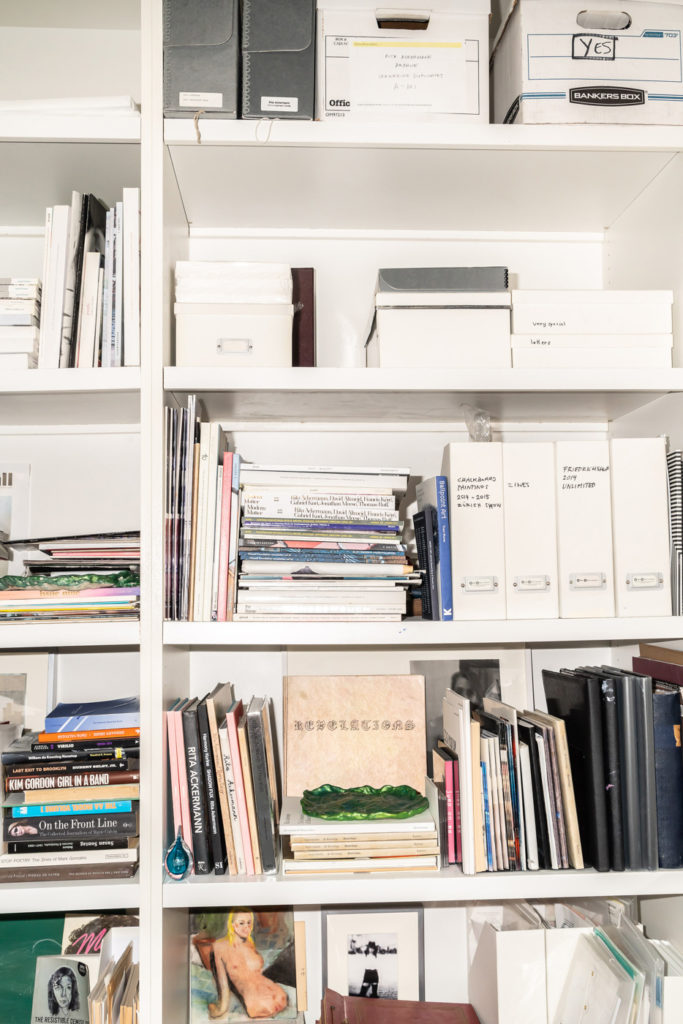

The morning of our meeting, I arrive early and catch a glimpse of the pair from a distance. It takes a moment to recognize Humm out of his chef whites, and the two are bundled appropriately as they approach. After cordial introductions, we enter her space and tour quietly at first, allowing Ackermann’s work to do the talking. It’s a rare treat to see a creative space in such a raw state, no one to interfere with how you might interpret a piece, with your own reflection and ability to connect. Still, I feel much less comfortable here than on a typical food shoot, in which I know what’s expected of me and how to behave. I’m accustomed to the sounds and smells and activity of a kitchen, which is always chaos even when controlled. Here there is silence and light and peace. It has a distinctive energy that feels almost sacred despite the industrial Brooklyn setting.

We begin our formal conversation, and Humm and Ackerman remain casual, affectionate. They give one another a chance to speak and remain engaged in the conversation, occasionally finishing each other’s sentences in good humor. When Ackermann speaks, Humm stands beside her, arms crossed and nodding along, engrossed reverently in her words.

“I’m drawn to a lot of women artists,” Humm tells me later. “It just happens to be that way.” He explains that his mother is very creative, that she paints and writes as well. “I think there’s a link. I feel that way with Rita. I feel this energy in her work—it’s just incredible.”

As they tell me about meals they’ve shared or their experiences as immigrants to the U.S. (Ackermann hailing from Hungary in the 1990s), it’s clear there is more than purely academic inspiration here. It’s personal. They’re old friends that share a shorthand, and while at Life & Thyme we frequently discuss the idea of food as the proverbial hand reaching across the aisle, it’s clear that in this context, art serves a similar purpose. Both offer an opportunity to communicate beyond traditional language, beyond culture, beyond boundaries, with a new voice. This dialect is as critical to his process of creation in the kitchen.

Later, at Eleven Madison Park, Humm points out the many ways he communicates the mission and philosophy of EMP beyond the food. It’s in the style of service, the interaction with guests, and also in the artistic touches around the room. They’re so subtle that most guests may not realize that included with their meal is a ticket to a museum—curated by Humm himself. There is, of course, work by Ackermann in a place of prominence above the dining room. “There was a painting here before of Madison Square Park by Stephen Hannock, a New York painter,” Humm recalls, gesturing toward her piece. “I asked Rita if she would be open to redrawing that painting on a chalkboard.” After she did so, Ackermann promptly erased it. Humm explains the idea being the resulting work now overlooking over the dining room, designed to befit the renovation: “It’s about erasing, and the new beginnings” that follow that erasure.

But less conspicuous pieces are on display in unlikely places, like the single stair over which each guest must step to reach the dining room—which just so happens to be made from the melted down pots, pans and other metals removed from the EMP kitchen prior to renovation by Daniel Turner. Or my personal favorite, a single, silver balloon sculpture by the Danish artist Jeppe Hein, subtly secured to the ceiling as if some over-excited diner released its string when their meal was set down and off it went. It is playful and enchanting—but easy to miss if you’re not paying close attention.

There’s something about seeing a person in the context of one of their chosen relationships that provides so much more clarity and insight than any question and answer could do. The story I originally intended to write about Daniel Humm was about art, and about the inspiration he draws from it in order to create his transcendent food—the dishes that have earned him the most attention a chef can ever hope to achieve. And that message was there. Humm tells me he values that art “makes you appreciate and slow down. You can’t appreciate a piece of art when you’re busy; you’re not open to it. Art is much more quieting to me.”

But I also found a chef who seems to derive more than a little of his creative juice from the people in his life. When he tells me about the artists that have populated the new Eleven Madison Park with their work, he begins almost every sentence with, “My friend, the artist,” and you get a sense that not only did Humm hope to infuse the restaurant with beautiful, dynamic artwork that complemented his dishes and provide an additional dimension to the diners’ experience, but that he genuinely enjoys being among the works of his friends.

When we tour the kitchen, Humm points out new equipment, describes what the space used to be and what has changed. It is astonishing how many people are on hand, each executing some task critical to making this restaurant the darling it is of diners and critics alike. Each greeting Humm and conducting her or his work while I do my best to stay the hell out of the way. We carve out the smallest corner of space Humm is capable of occupying with his six foot-plus frame, and as we wind down, I thank him for his time and hospitality, ready to bow out so he can prepare for service. But before I take my leave, he turns the interview around, asking me about my work and my life. This may not seem unusual to the average reader who assumes that conversations often go both ways, but I can assure you, many interviews end and I leave wondering whether the subject ever caught my name, let alone what I do with my spare time.

This kind of curiosity and interest in other humans not only makes Humm unique in the conversational space, it’s indicative of an empathy—an interest in connecting—and at its core, that is what art of any kind is all about, right?

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.