The Raw Beef Tonic

In cultures around the world, the consumption of beef in various raw forms has been part of cuisines for ages.

Words by Ilana Sharlin Stone

Illustrations by Julia Webb

When I was a kid, my mom often gave me raw ground beef when I had a cold or the flu. Not a hamburger patty’s worth. More like a heaping tablespoon. From under the covers in my parents’ bed, bleary-eyed from fever and watching way too many Gilligan’s Island reruns, I’d see her appear: a maternal vision, offering a pinkish smear of seasoned ground chuck from her dulled stainless-steel chopper.

To me, this was a much better remedy than throat lozenges. The meat she lightly seasoned slid down my sore throat, cooling it along the way. It made me feel better, though I didn’t know why.

When I reached adulthood, I began to wonder: why the raw beef?

The question surfaced whenever I pinched off a lump of raw meat, sprinkled it with salt and popped it in my mouth, before turning it into burgers or pasta sauce. By then, this had become a kitchen habit, further entrenched once I discovered steak tartare and carpaccio. Knowing these were delicacies somehow made me feel as if my behavior was more cultured and acceptable.

Several years ago, when I knew that at ninety my mom, I finally asked my mom about her raw beef remedy. By then I was convinced it must have had Eastern European Jewish roots—an Ashkenazi link to fortitude. “Mom,” I asked. “Was this something grandma gave you when you were sick?” This didn’t seem crazy; my dad’s mother tightly strapped a halved potato to his forehead whenever he complained of a headache.

But my mom looked surprised. There was a pause, and then that characteristic ladylike clearing of her throat, which I’d give anything to hear again. “Ilana,” she said. “I gave it to you because you loved it.” Her answer brought tears, and more questions.

For decades, I’d believed raw beef was a tonic. The Center for Disease Control hadn’t agreed. Its website states: “Ground beef dishes should always be cooked to 160°F internal temperature as measured with a food thermometer.” Since my mom died, I haven’t been able to shake the idea that my love of raw beef has ancient roots. I imagine many paleo followers and raw foodists would back me on this.

I’ve also become curious about its global appeal, because like so many Americans, raw beef meant only two dishes to me: tartare and carpaccio. Yet these two are mere toddlers in the world’s family of raw beef delicacies. So I decided to learn more.

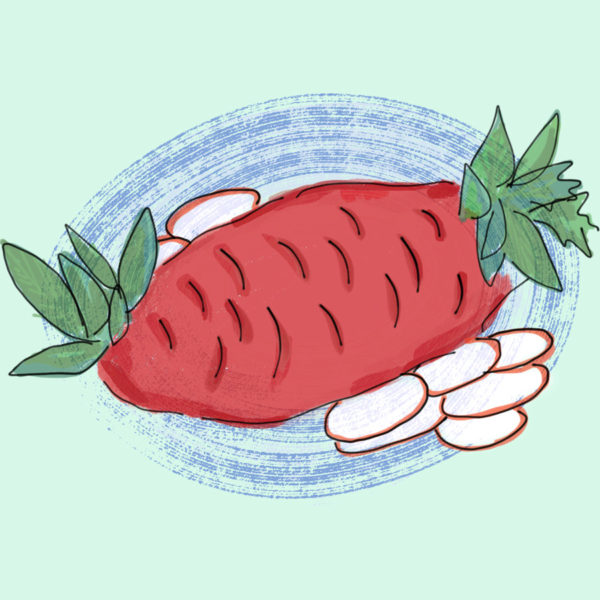

Kibbeh Nayeh

Lebanon

Kibbeh nayeh is widely considered the national dish of Lebanon, with a heritage that likely goes back to the time of Abraham. “Kibbeh nayeh has that special quality of being both deeply Old World while remaining consistently contemporary and relevant,” says Maureen Abood, the Lebanese-American food writer behind the cookbook and blog, Rose Water & Orange Blossoms. As the granddaughter of four Lebanese immigrants, she has fond memories of its meticulous preparation and of eating it around the family table as a special occasion dish.

“As a baseline, it is a mixture of extremely lean raw beef or lamb, trimmed of all fat, finely ground, and mixed with bulgur wheat [half meat, half bulgur in Abood’s recipe, along with seasoning and pureed raw onion],” she says. “Regionally in Lebanon, kibbeh is seasoned in various ways, using herbs such as mint and marjoram and spices like cinnamon, allspice, cayenne, cumin, black pepper, salt, and even dried rose petals.” The meat is then shaped in an impressive large oval mound, to be immediately scooped up with pita bread and eaten.

Hygiene and fastidiousness are paramount to the preparation of the beef, from the equipment used to the careful removal of any fat or sinew. “First and foremost, Lebanese butchers will tell you kibbeh meat should always be ground to order on clean blades. Don’t even think about using the pre-ground meat in the supermarket display case,” Abood says. “In the eras before meat grinders, the Lebanese pounded the meat mortar-and-pestle style. Today, kibbeh meat from the butcher should be ground first thing in the morning, on a sparkling clean grinder to avoid cross contamination, which is why trusted butchers will rarely take a same-day order.”

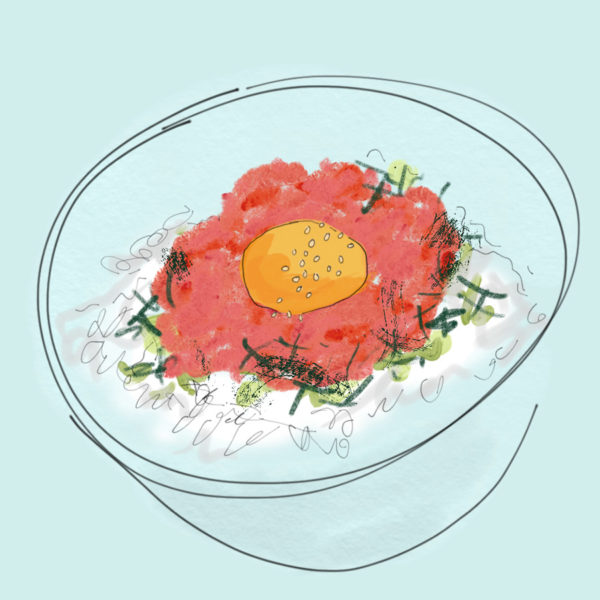

Yukhoe

Korea

Yukhoe, which also means “raw meat: in Korean, is a dish of very thinly sliced raw beef, usually mixed with sesame oil, soy sauce, and pine nuts, served with a raw egg cracked over the top. Sometimes it’s accompanied with julienned bae (Korean pear). It was one of many dishes (including the now popular grilled meats), brought to the Korean Peninsula by invading Mongols in the thirteenth century, according to Michael Pettid, professor of Korean Studies at Binghamton University and author of Korean Cuisine. As beef was a commodity, it was associated with aristocracy. “Every part of the cow was used, even the blood and bones,” says Daniel Lee Gray, a Korean food and hospitality expert in Seoul who pens the blog Seoul Eats. “The fattier cuts were grilled, but the leaner cuts were eaten raw after fortifying them with sesame oil and egg yolk and sweetening them with pear.”

“In contemporary Korea, some old foods are being reinvented or reshaped to create more appeal among young people,” says Pettid. “Part of that trend is finding old dishes and emphasizing the health benefits and links with ‘traditional Korean cuisine.’ So, at a trendy restaurant, yukhoe is trendy. At a typical and unpretentious grilled meat house, it is a simple dish that has been served for many years.”

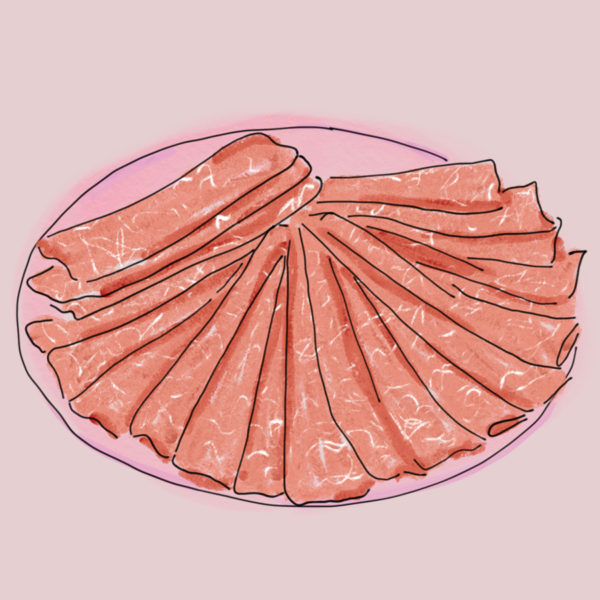

Wagyu

Japan

Meat eating is—in the big picture—new to Japan. It only became common practice at the end of the nineteenth century when Emperor Meiji, who had an intense fascination with Europe, opened up Japan to the world. “Historically, Japanese ate mostly vegetables, rice, some fish and fruit; Buddhism and Shintoism prohibited the consumption of any type of meat in any form,” says Andrea Fazzari, Tokyo-based photographer, writer, and author of the new book Tokyo New Wave: 31 Chefs Defining Japan’s Next Generation.

Today, dishes prepared with highly marbled raw wagyu—a word which translates to Japanese cow—are popular. Most common are beef tataki (filet that is seared but still very rare, marinated and thinly sliced like sashimi) and what is called tartare, says Fazzari. Yet contemporary chefs are experimenting with other preparations.

Kentaro Nakahara is the chef at Sumibi Yakiniku Nakahara, a yakiniku is a Korean-style grilled meat restaurant in Japan. “To serve raw beef, the chef must have a special license to clean and prepare it,” says Fazzari. “Nakahara has one. Not just any restaurant is allowed to serve raw beef, to safeguard improper handling of meat and potential associated illnesses. Nakahara serves many different parts of the cow including gyutan (tongue), which is a popular specialty, as well as wagyu sushi.” He also serves yukke—chopped raw beef with a raw egg on top—which comes from the Korean raw beef dish, yukhoe.

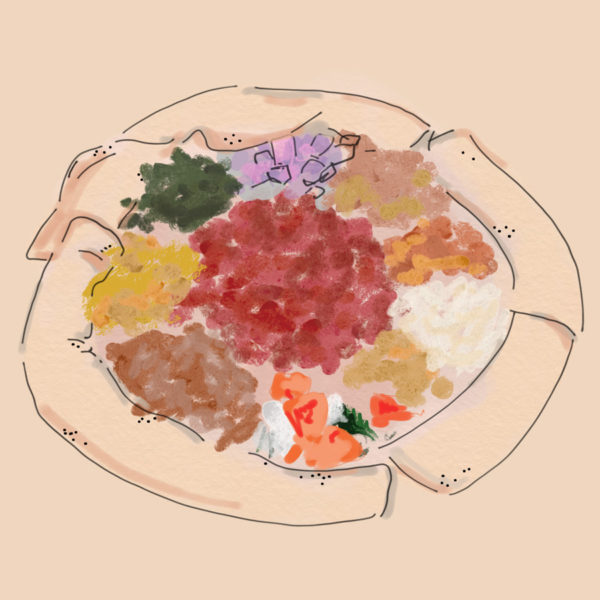

Kitfo

Ethiopia

Raw beef is prized in Ethiopia, with a history that goes back centuries. If you’ve eaten in an Ethiopian restaurant in the U.S., you’ve probably seen kitfo, a dish of chopped raw meat, seasoned with mitmita (hot red pepper powder), cardamom, and niter kibe (clarified butter stewed with spices). This is only one of many Ethiopian raw beef dishes and the one best-known in the Diaspora. It’s very much “a twentieth century adaptation,” according to James McCann, a history professor at Boston University considered a world expert on Ethiopian food, and author of Stirring the Pot, a book about African cuisine. Kitfo comes from Ethiopia’s Gurage—a group which makes up about 2.5 percent of the population—yet the dish has spread to the rest of the country and beyond.

“One story goes that Ethiopians began eating raw meat because while at war centuries ago, the men in the field couldn’t afford to cook their meat; the enemy would see the smoke from the fire,” says Harry Kloman, author of Messob Across America.

Steak Tartare

France

There is a widely held myth that steak tartare originated with Mongol horsemen, who according to a 2005 New York Times article by writer Craig S. Smith, “swept across Central Europe eight hundred years ago. The most common tale is that Tatar horsemen would place a slice of horsemeat beneath their saddle in the morning and retrieve it, tenderized by the pounding, to eat raw for dinner.” The article went on to debunk this theory with further research, which suggested after a day under a sweaty saddle, this meat would have been inedible.

Nevertheless, today’s steak tartare—raw ground beef topped with a raw egg yolk with accompanying capers, chopped onion, and parsley—originated in French restaurants in the 1950s and is still a fixture on French menus. “Generally, it’s offered as a main dish accompanied with crisp fries or potato wedges and a green salad, though modern bistros and fine dining restaurants may incorporate tartare into a creative starter,” says Lindsey Tramuta, the Paris-based journalist and author of The New Paris. Recently, she even saw it stuffed into baby tartelettes.

Enjoying raw beef may not for everybody, but it has widespread relevance in our world. “Many nationalities have raw meat dishes in their cuisines, dishes that are deeply etched in their cultural history and identity,” said Abood. “I don’t think that the common thinking was that consuming raw meat made you sick. This has become the thinking over time as meat became procured from mass producers or even butcher shops unfamiliar with raw meat practices. Happily, raw meat dishes, properly made, have survived despite that.”

Pettid adds, “This is the kicker for most people in the West as we have been thoroughly indoctrinated to not consume raw or undercooked meats. This was true in the 1970s when Japanese-style sashimi first started appearing on the West Coast and people worried about parasites,” he says. We fear contamination via e-coli or salmonella. But Pettid argues, “These dishes were developed centuries ago when there was no knowledge of bacteria and also no refrigeration in the modern sense. Freshly slaughtered beef was prized. It was actually the beef that had been stored that caused sickness.”

Wherever you stand on eating raw beef, historically, there is evidence that it was considered good for you, dating back to sixteenth century references in Exemplar of Eastern (meaning Korean) Medicine. As Pettid says, “The medical benefits from consuming beef were highly touted and applying freshness to the equation makes it clear why yukoe was a highly prized dish for those who could afford it.”

In these cultures (and many others), raw beef signaled freshness, and it was a rare treat—something to be celebrated. Naturally, it became absorbed into other celebrations and life cycle events. To me, it’s certainly had special healing power, simply thanks to a mother’s love.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.