Africa — Nov. 17, 2020

How Recovering African Crops Could Address Lost Cuisine

To improve food access, Sub-Saharan Africa can rediscover lost native food plants, and embrace cuisines as diverse as the many cultures and traditions that are found on the continent.

Words By Daniel Muraga

Photography by Daniëlle Siobhán

This story is published in the fall 2020 issue of Life & Thyme Post, our exclusive newspaper for Life & Thyme members. Get your copy.

When Mark Zuckerberg visited Sub-Saharan Africa in September of 2016, he posted about enjoying jollof rice in Nigeria and ugali in Kenya. Yet, like so many travelers seeking out local food in other countries, Zuckerberg was likely unaware that what he was eating was hardly African at all.

Jollof rice in Nigeria is an expertly prepared dish of rice, tomatoes, tomato paste, onions, and Scotch bonnet peppers. Zuckerberg might also not have known that ugali is a popular dish in Kenya made from maize flour. Like all other visitors and a majority of natives, it is hard to differentiate eating in Africa from eating African. This is because much of what is eaten in Africa is not native to the continent, as exemplified by the widespread consumption of spinach (such as in Kenya, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Botswana) and cabbages (such as in South Africa, Ghana, and Uganda), for example.

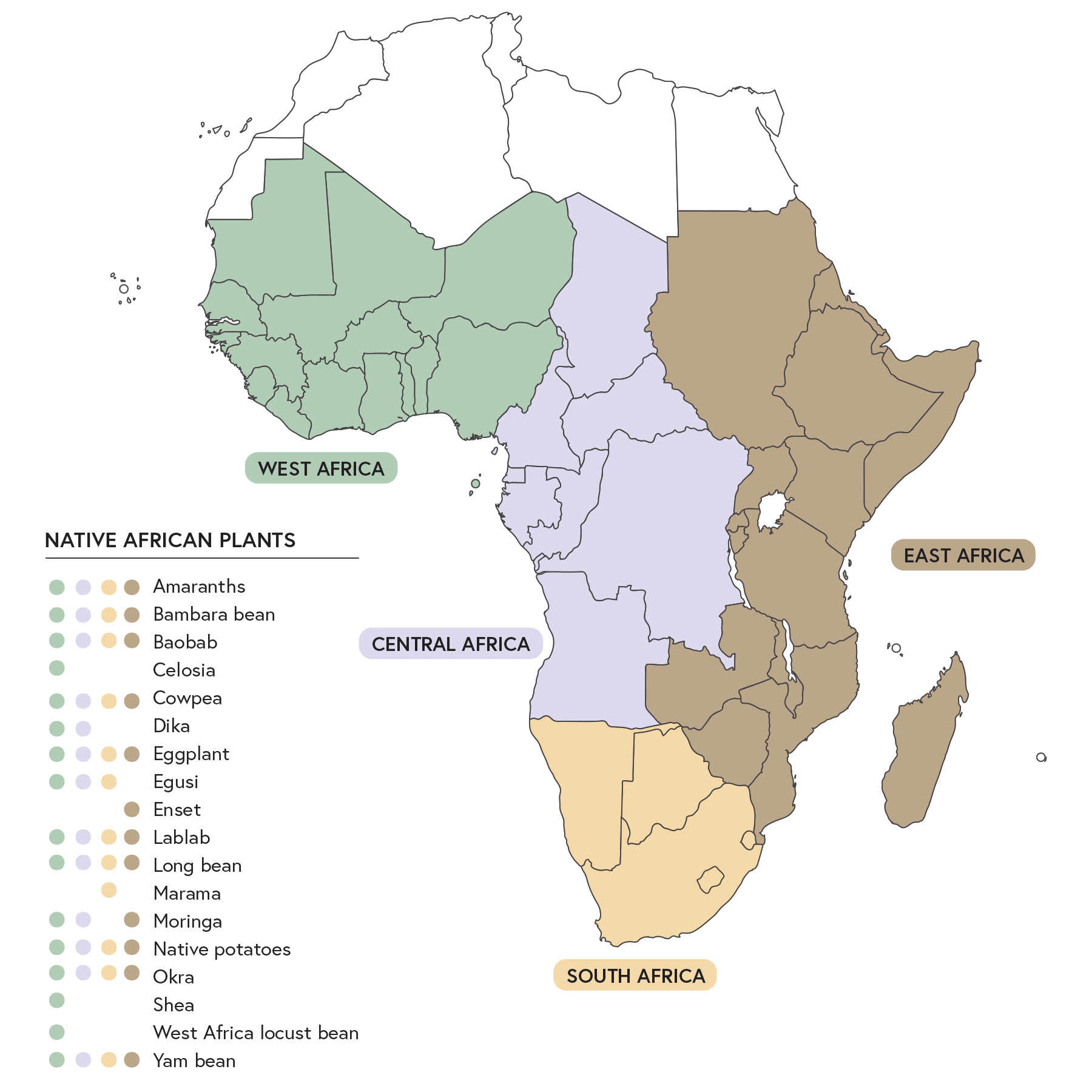

There are, however, hundreds of native food plants that can greatly promote and enhance the food supply base. The eighteen most important of these plants to mention here include: amaranths, bambara bean, baobab, celosia, cowpea, dika, eggplant, egusi, enset, lablab, long bean, marama, moringa, native potatoes, okra, shea, West African locust bean, and yam bean.

Among these indigenous plants, all but enset and marama thrive in West Africa. In Central Africa, all these plants do well apart from celosia, enset, shea and locust bean. Additionally, the climate is beneficial in East Africa for all apart from egusi, dika and shea. In Southern Africa, all these crops thrive apart from shea, moringa, enset, dika and celosia.

Only a few of these food sources have received sufficient scientific research, mainstream food promotion, or any meaningful inclusion in the conventional nutritional schemes. Yet scholars in a journal published by Molecular Diversity Preservation International (MDPI) posit that, “indigenous and traditional foods crops (ITFCs) have multiple uses within society, and most notably have an important role to play in the attempt to diversify the food in order to enhance food and nutrition security.” Now is the time to rediscover these forgotten plant food sources in order to increase food access in Africa.

Oriaku Clementina, executive director of Initiative for Adequate Nutrition (IFAN), agrees that indigenous food plants could be harnessed in order to improve dietary diversification. “Research has shown that our African indigenous foods are easily accessible and affordable sources of much needed nutrients,” Clementina says, adding that, “rediscovery and encouragement of increased cultivation and consumption of food plants that are indigenous to Africa is a step in the right direction, and will immensely support the fight against malnutrition in all its forms.”

Early Indian Ocean trade between the East African coast and Asia, which began around 800 A.D. continuing through and declining in the 1500s, brought about new food sources such as sugarcane, bananas, and most notably, rice. However, Africans still relied heavily on indigenous food sources up until 1441 when European explorers and slave traders came sailing West Africa’s coast.

This trade continued from the sixteenth through to the nineteenth century bringing the Americas on board. This is when Sub-Saharan Africa tasted and adopted American food crops such as common beans, pumpkins, groundnuts (peanuts), corn (maize), tomatoes, chili (peppers), and sweet potatoes. These new plants enjoyed widespread acceptance and quickly became important to African cuisine.

Then came white settlers in the nineteenth century. Colonial masters imposed land alienation and brought about European commercial farming. This meant Africa’s traditional crops dwindled even further. New crops—which included coffee, tea, cocoa and chocolate—were considered more valuable, profitable, exportable and non-perishable. Since the arrival and influence of foreigners, Africa has been sustained by twenty or so food species, the majority of them not being indigenous to the continent.

Today, common food dishes do not have as many native vegetables. “[These native plants] deserve attention from government and research institutions,” Gilbert Tshitaudzi, a nutrition specialist with UNICEF (South Africa), says, alluding to the nutrient density of these species. Tshitaudzi continues that, “these traditional food plants have a role to play if they can be massively produced, their nutritional content documented and understood, to ensure that they are promoted to address specific nutrients gaps of concern.”

Africans have traditionally integrated hundreds of vegetable species into their diets. But some of these food sources were eventually discredited by colonists as poisonous, like cassava. This staple crop in Africa is said to have cyanide toxins in its leaves and tubers. But the negligible level of this toxin, which the plant uses to fight pests, is harmless to humans and can still be further reduced by proper food processing. The ingredient is foundational to saka-saka in Democratic Republic of Congo, a national dish consisting of boiled cassava leaves, peanut butter, palm oil, and smoked fish. In Malawi, cassava flour is used to make kondowde.

The most common vegetables in Africa today are plantains, sweet potatoes, white potatoes (especially in East Africa), beans, cassava, and groundnuts. Popular vegetable crops for the continent’s largest economy—South Africa—includes tomatoes, potatoes, green and sweet corn, cabbages, carrots, onions and beetroots.

In countries such as Uganda, Tanzania, Madagascar and Rwanda, the most prominent crops are plantain bananas. In Ethiopia, there are lentils and chickpeas. In the tropics, there are abundant peppers, okra, eggplants, cucumbers and watermelons. If you are looking for palm oil, coconuts and kola nuts you need to be in Nigeria, Ivory Coast, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The current generations in Africa consider these sources grown in their countries as native to Africa.

There are several efforts being made at ensuring Sub-Saharan Africa uses home resources to promote nutrition and sustenance. As Tshitaudzi tells us, “at UNICEF, we promote a diverse diet which includes amongst others: vegetables, fruits and tubers. These may also include some native food crops if they are included, setting as part of a diverse diet.”

Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity, for example, is creating ten thousand gardens and activating a network of young leaders in Africa who are working to save the continent’s amazing biodiversity, promote traditional knowledge and gastronomy, and support family farming and small-scale agriculture. The foundation also identifies and catalogues quality food products at risk of extinction.

Additionally, AVRDC offers a gene bank collection to address specific needs of crop breeders worldwide. Over time, it has grown into a multiple-use anthology for research and development at the worldwide level. It currently has 438 vegetable species now included in its gene bank collection giving it the ability to not only to conserve, discover, and utilize vegetable biodiversity, but also to add to the diversification of vegetable production systems and use patterns in the developing world.

IFAN, on the other hand, is promoting and providing evidence-based nutrition information, improving access to safe and quality food, while championing nutrition for good health in Africa. It aims to empower people to make positive lifestyle changes to improve nutrition, preserve health, and save lives. And as Clementina tells us, “We aim to equip people with information they can use to improve their diets.”

Eunice Nago Koukoubou, a nutrition and food security specialist from Benin, asserts that the real African nutrition problems are not being addressed because African researchers fail to take responsibility in identifying and solving the problems of their own populations.

“[Native plants] deserve every attention they are now getting and more,” IFAN’s Clementina says. “Take, for instance, bambara groundnut, which has been praised by researchers as a complete food owing to its very rich nutrient profile. It provides a cheap and readily available source of carbohydrate, protein and fat, among other nutrients, especially in Southeastern Nigeria where it is a staple.”

In a study Clementina conducted on the effect of aerial yam on postprandial levels of diabetic outpatients at University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu, her findings demonstrated that the yam “had immense potential to be hypoglycemic and would successfully feature prominently in the diets of diabetic patients and improve diversity.”

Today, some research organizations and national archives list some African food sources as weeds, deepening the undesirability of these options. Take, for example, amaranth in East Africa. This nutritious vegetable grows spontaneously on its own on farms during rainy seasons. However, the plant is uprooted to give way for cash crops like coffee, maize and beans. African yam and okra suffered the same fate, alongside other nutritious and native African food crops.

Africa’s yam and okra are some of the most popular traditional crops on the continent. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) highlights a growing area for yams that includes Nigeria, Benin, Cameroon, Togo, Ghana, and Ivory Coast. The zone produces ninety percent of all yams worldwide. In addition to coming second after cassava in providing starch in the continent, yam tubers can be stored for four to six months without refrigeration.

On the other hand, okra provides pods, seeds and leaves, all of which come loaded with vitamin A, B6, folic acid, protein, calcium, iron, and other minerals. The plant is believed to have originated from Ethiopia and was cultivated in ancient Egypt by the twelfth century B.C. This plant is popular not just in Africa, but all over the world where it is known by different names, like ladies fingers or ochro. In India, the plant is called bhindi. And Southerners in the United States associate it with gumbo.

Yet, many African native food plants have received little or no attention in terms of mainstream scientific and agricultural research and promotion. Like in commerce, competition is good in agriculture. If given fair ground, these “lost” food sources would compete favorably. The best climatically-suited crops are the best bets if any battle to feed a vast continent like Africa is to be won.

If Sub-Saharan Africa can consider native plants in a meaningful way, this can go a long way in eliminating hunger. Africa is a large continent with diverse climatic conditions for different crops. In the most extreme and blistering climatic conditions of Kalahari Desert, there are tens of documented food crop species that have been used by natives in Namibia and Botswana. If there is such a huge number of traditional food crops in semi-arid and arid areas, what about in the fertile African highlands, plains, savannas, valleys and temperate areas? There are more than three thousand documented tubers, roots, leaves, stems, stalks, fruits, and others that were consumed in the ancestral times.

Unfortunately, not much of this wealth is well preserved. This is because the knowledge of what is palatable and what is not was usually passed down through generations by word of mouth, especially from mother to daughter. When she was cooking amadumbe (taro roots) at the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, Nompumelelo Mqwebu (a popular star chef in South Africa) was surprised that most Africans had no clue what these tubers were even though they have been grown in KwaZulu-Natal for ages.

There is a need to explore reliable new avenues to achieve food security, and to promote native and drought-resistant crops in a continent strongly affected by climate fluctuations, conflicts, corruption, natural disasters, and other catastrophes.

Plants can also improve rural economics and sustainable land care. As Clementina notes, “there are many other neglected and forgotten plant foods in Africa that are simply not enjoying enough attention considering how much nutrients they contain and how they can aid households in diversifying their diets without breaking the bank.”

“I would be most pleased to see research geared around rediscovering such indigenous plant foods and improving their nutrient profile through agricultural-biofortification practices,” she tells me, adding that, “we can identify other African plant foods that can serve as vehicles for biofortification and rekindle interest in them by making them more available in the mainstream markets. This will certainly serve to strengthen our efforts in tackling micronutrient deficiencies.”

A large number of people in Africa still depend on small-scale farming for food. Therefore, policies that touch on farming systems at the subsistence level have a direct effect on food availability and consumption. Policies that aim to rediscover lost native food crops will have strong and direct impacts on sustainable food access. The loss of native food crops means loss of culinary identity, but by harnessing and rediscovering African native food plants, African societies have a chance to make a meaningful, lasting improvement to food security and the health and prosperity that accompanies it.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.