I walk into Downtown L.A.’s Broken Spanish on a December day to a bustling kitchen prepping for evening service and a warm welcome from chef/owner Ray Garcia. It’s easy to be distracted by the array of dishes being built around me in the sunny restaurant—the aromas of braises and sofritos, heirloom tortillas, and mole sauces—all building blocks of the dinner menu so many guests will enjoy in just a few hours. But I’m here for something very specific: the tamal.

I join Garcia in the kitchen along with his cook, Rosario, who is smearing masa (corn dough) with admirable precision onto corn husks laid out in perfect rows. I am mesmerized by her skill. Having grown up in a Mexican household on the Texas/Mexico border, the Christmas tamalada—the assembly line of family and friends who gather around the holidays to whip up tamales—is familiar. Tamales were never lacking in our household; ours were purchased from the tamalero who still makes his requisite rounds to sell his homemade goods, of which my mom buys dozens. Although they’re enjoyed year round, in Mexican culture, tamales are mainly considered a holiday food.

Traditional pre-conquest tamales were filled with beans or squash, but there were also variations made with duck, turkey, venison, lobster or crab with some sort of chile or tomato-based sauce. Post conquest, Old World ingredients like pork, beef, chicken and cheese make an appearance, including sweet variations, as well as tamales wrapped in banana leaves, a plant native to Southeast Asia. French-style cookbooks of nineteenth century Mexico describe tamales as a type of delicate stuffed bread made of corn that Spaniards ate with gusto.

Today at Broken Spanish, Garcia introduces me to an intriguing new filling: braised lamb neck. A lamb tamal is new to me, but once he puts it on the griddle, the edges of the masa begin to caramelize and crisp, and the aroma rises to meet me; I’m totally in.

Plated on a cast iron dish and topped with more filling, the humble ingredients are gorgeous to behold and truly extraordinary to eat. With the combination of meat and cheese, sauce, a little heat, and perfectly earthy masa in every single bite, I feel like I’m being transported to ancient Mexico; it’s a new take on the tamal for me, but still with surprising Old World flavors.

In Garcia’s kitchen, on the days Rosario takes up the tamal task, she makes about one hundred at a time. A labor intensive process, tamal-making has been a social event led by women since pre-colonial times. Today the tamalada rekindles the ritual of women gathering in the kitchen to make something cherished throughout the holidays. The many hands required for the assembly line is a great excuse for family and friends to get together—which is, after all, what the holiday season is all about.

For many Latin American families living in the United States, these portable foods are a taste of home. The leader of the tamalada pack in Garcia’s home was his grandmother. “As a kid, you don’t realize how special [the tamalada] is, or see the value of it until later in life,” he tells me. “As a cook, when I decided I wanted to focus on Mexican food, tamales were one of the foods I loved and wanted to share with people, because they have such a strong tradition in my food memory.”

Garcia’s family gathered at his grandmother’s house on Christmas Eve. She would prepare the pork with red chile filling while his grandfather took charge of the physically demanding task of mixing the masa. Young Garcia was relegated to counting corn husks and laying them out. Although today he recognizes this was busy work––a way to help him feel important and included.

“I probably can’t list ten Christmas presents I received in my childhood that had as much impact as coming together, having the Christmas tree up, having something in the oven, and having tamales steaming,” he recalls. After the tamales were in the steamer, the family would head to a nighttime church service, which Garcia describes as, “Torturous. You’re sitting there the whole time starving and waiting for the tamales to be ready. But maybe that anticipation made them even more exciting and delicious.” It’s not difficult to imagine Garcia waiting for that first tamal bite with the same anticipation as waiting for Santa Claus.

Garcia and his Argentinian wife plan on carrying on the tradition with their own young son. “It’s fun and something kids can do,” he says. “Maybe it’s messy and maybe it’s not going to be the prettiest tamal, but it’s about getting your hands dirty, getting in there, steaming it, and feeling included.”

His memories are also vivid of the Christmas “tamal swap;” family members would visit relatives with a batch of homemade tamales, which became a sort of family stamp. Sometimes your family’s stamp ended up on the table, sometimes in the freezer, but Garcia says it was always clear “who didn’t salt enough or whose were too spicy, because everyone had their own style.” His grandmother was always very precise about how much went into each tamal to avoid the ultimate disappointment: a tamal that looked “so good, so big, so round, then it just didn’t have that right ratio, or the leaf is stuck in the middle and it falls apart when you open it.” Or worse, “when there’s only an olive.”

The idea of a tamal with an olive (an ingredient native to the Mediterranean) is part of a larger story—the influence of colonization and immigration on Mexican cuisine. Adopting new food traditions and connecting them to the past brings into question the big ideas of authenticity and innovation. Garcia doesn’t shy from experiments with seasonality; he describes a sweet tamal of roasted pumpkin, vadouvan (a French-style curry), pomegranates, yogurt, and collard greens currently on the menu at Broken Spanish.

Garcia is a native Angeleno. “From a chef’s standpoint, I couldn’t see myself happily cooking anywhere but Los Angeles,” he tells me. “The city itself is amazingly diverse with so much inspiration from everywhere. [In] going to a Korean barbecue restaurant and picking up an idea, going to Chinatown, going to the Santa Monica Farmer’s Market—it’s this constant stream of ingredients and opportunity. L.A. is special from a creative person’s standpoint.”

He adds that some people might question whether this can be considered truly Mexican food. “Tradition and authenticity are subjective,” Garcia believes. “I try to use the word familiar instead. Broken Spanish has its own traditions that aren’t necessarily mine or my family’s, but we contribute to it; and each chef who comes in is part of the tradition that is the restaurant’s. Maybe when Rosario goes home and makes tamales over the holidays she will have new ideas that might impact what she does in her own home, and that’s passed down to generations. I try to challenge that idea of tradition and authentic as being limiting labels. Anything that somebody does repeatedly over time with a certain impact can be considered a tradition—good or bad.”

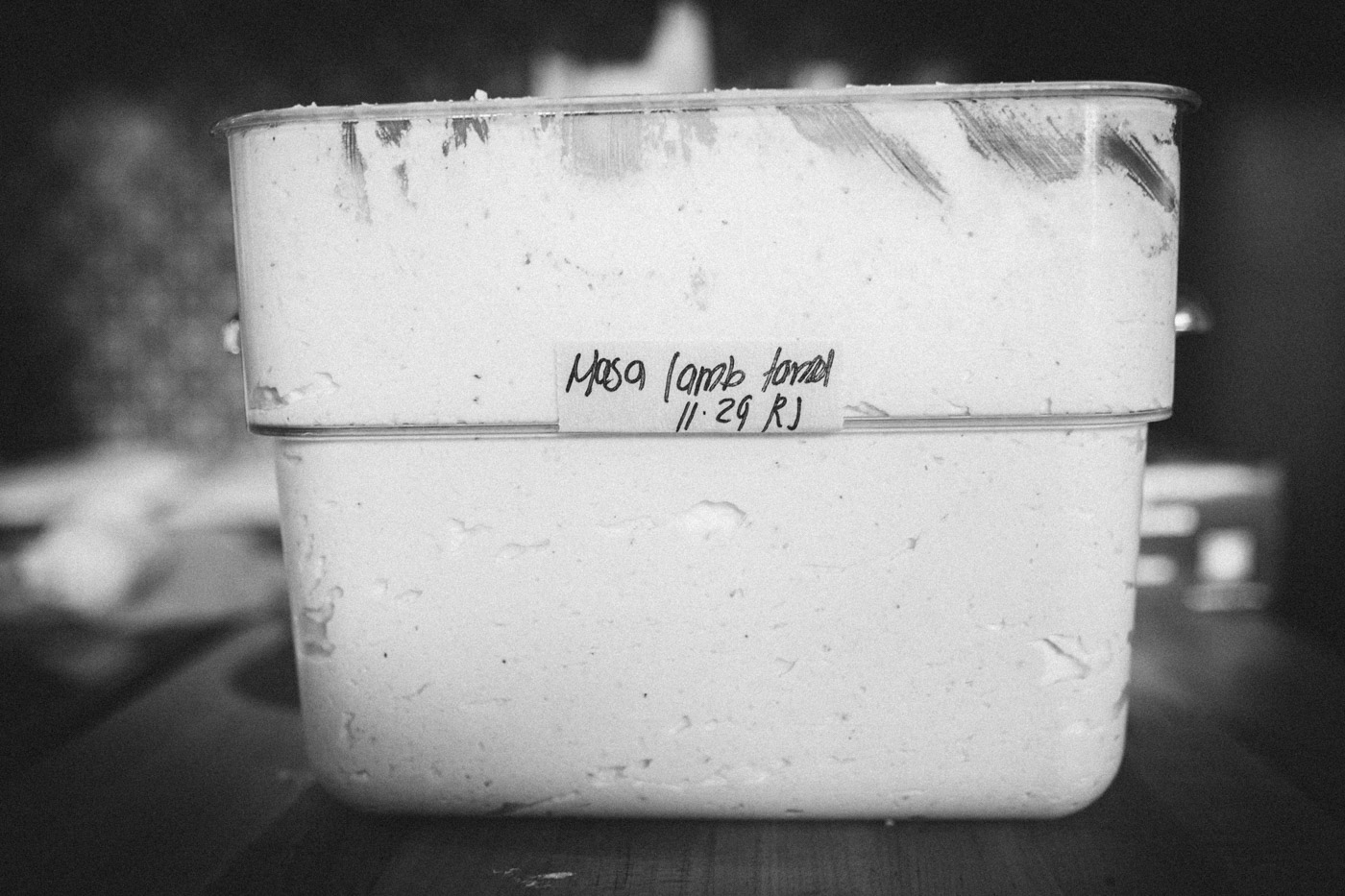

But part of Garcia’s tamal is undeniably traditional, and that is the soul of the dish: the masa. The masa he uses for his tamales is sourced from Masienda—an importer of landrace maize from Mexico—by way of his friend, Chef Carlos Salgado, at Orange County’s Taco María. Salgado grinds corn at his restaurant for Garcia, and both chefs work with Masienda’s corn across their menus—a gesture that not only shows a deep respect for the ingredient, but for the farmers who toil the land and for the origin of the food itself.

“The masa we use is so special and so unique and so different; the only other tamales I eat are Carlos’ because he uses the same masa,” Garcia says. “Once you get used to it and you know what goes into it, you want to support it and want to have this great land-raised heirloom corn.”

Maize (corn) is Mexico’s original domesticated crop and the life force of the Americas. Corn was so significant in pre-Colonial Mexico that according to the Popol Vuh, the Mayan book of creation, humans were created from masa. The Olmecs, Mayans and Aztecs all worshipped maize gods and goddesses and ate tamales as a form of religious communion, and tamales were served at agricultural rituals and ceremonies.

Naturally, during the conquest, Spaniards supplanted the corn with wheat, which had similar religious connotations for them, as the crop of choice as part of Catholic evangelization. Yet ironically, tamales are eaten during the Christmas holidays—a Christian celebration—all over Latin America. So what happened?

Well, old habits die hard. Even though corn was thought of as inferior to wheat in colonial Mexico, tamales were still considered nutritious and delicious by people from all walks of life. And the holidays—which for Mexicans extend from the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe on December 12 through Three Kings Day on January 6 with tamales served throughout—were the perfect time for them.

Tamales are still eaten with gusto around the holidays thousands of miles from their country of origin and with centuries of cultural adaptation and assimilation. For Garcia, the “warm and steamy little packages you open with excitement” are a humble yet complex dish; the secret and universal ingredients are the memories attached to them.

——

Ray Garcia is the chef and owner of Los Angeles’ Broken Spanish and BS Taqueria. You can watch more of his story on a recent episode of our Emmy-winning show, The Migrant Kitchen, on KCET.

Correction: We have changed singular version of tamales from tamale to tamal.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.