A few years ago, I moved to Los Angeles with a mission. I’d been hearing nonstop about the city’s dining renaissance. As a total restaurant geek, I needed to try all the best spots, eat every new and exciting thing and immediately begin enumerating a vast edible laundry list. I consulted folks I trusted in all things food, but to my surprise, the recommendations were nothing like the hip, trendy spots I’d come to expect in New York City. Instead, many were out of the way, not to mention my comfort zone. They were places I couldn’t pronounce, in neighborhoods I’d never heard of, occupying signless strip malls I’d have passed right by, representing parts of the world I didn’t even know existed.

“It’s on Gold’s list,” my friends would tell me. Or “Gold gave it a rave.”

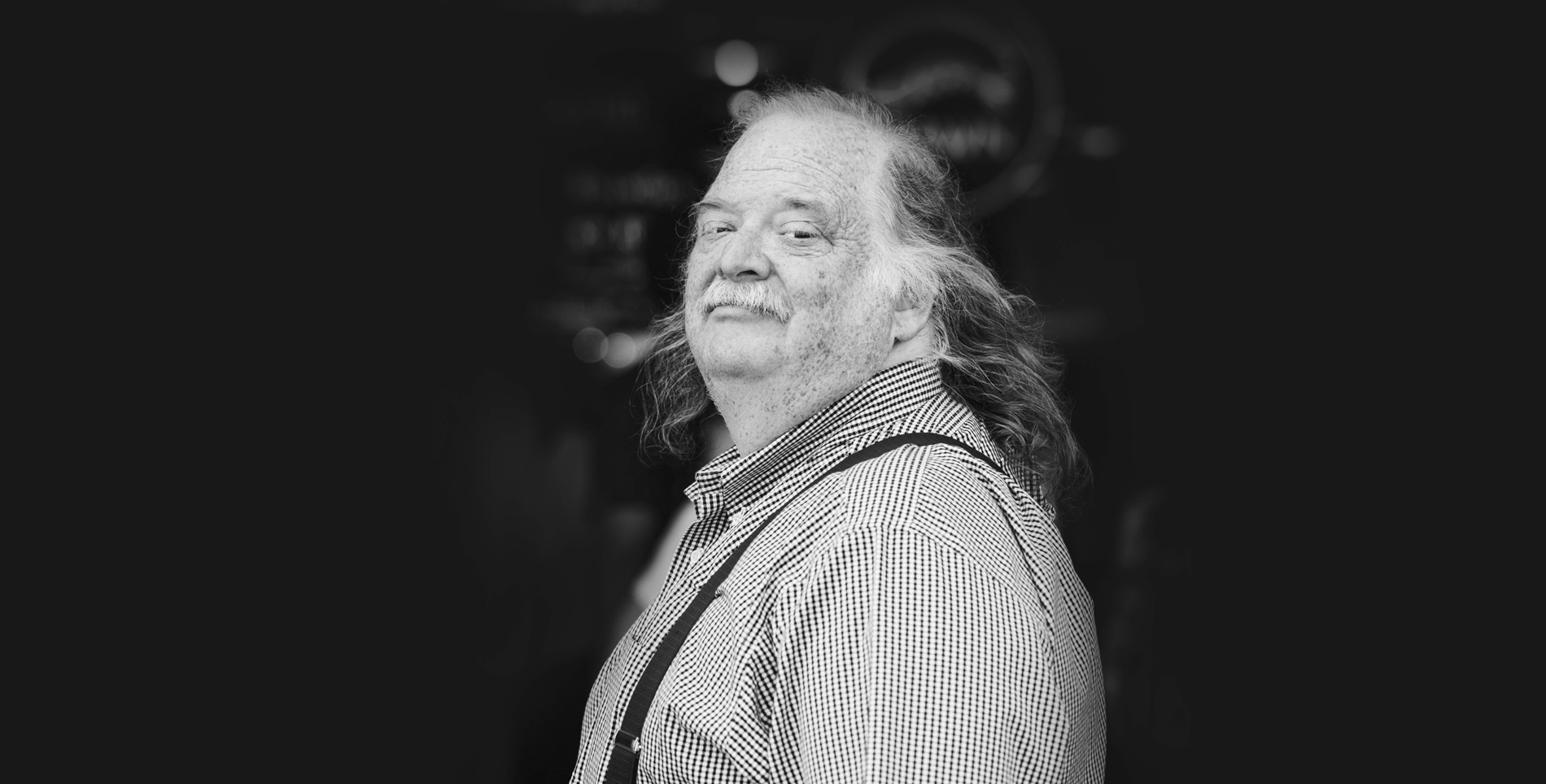

I had no idea who this mythical figure was––this Great and Powerful Oz of Angel City. And when I was told he was the resident food critic, I’ll admit, I balked. I had by that point developed some pretty strong opinions about that particular role in food culture. In New York, he or she who wielded and bestowed the coveted stars literally held lives and livelihoods in their hands. The kind of career make-or-break power felt so unfounded to me. Who was any person––regardless of palate sophistication or culinary prowess––to sit on high, doling out judgement to my friends, colleagues and neighbors? Whose interests did the food critic really serve anymore?

Of course anyone familiar with his work could have told me that in Jonathan’s case, the answer was simple: the interests of his city. And after taking the advice, and a seat at some of the restaurants he celebrated, I became a firm believer.

As a diner, he was an oracle. As a writer, Jonathan was an example. Evaluations of a restaurants’ preparations were in his reviews, of course. Some were not to be missed; others might simply be “fine.” Missing from his summations, though, were the snarky, condescending, and sometimes downright mean-spirited quips of so many contemporary food critics.

And each dish was really just the serving plate on which Jonathan arranged his grander compositions: commentary about culture, community, and humanity. He set his urban scenes prosaically––from Little Tokyo to K-Town to the Santa Monica Pier. Jonathan wrote about food in black and white typeset. But the stories he masterfully lay between each line of newsprint is what earned him a Pulitzer Prize, and the adoration of an industry. For the first time, I saw thoughtful, insightful and informed food writing as a matter of populace––not popularity.

As a newcomer with some apprehension about living in LA, his body of work was a guidebook. But it wasn’t about the food; it was in his words that my new city became accessible. Exciting. Compelling. Romantic, and even tragic at times. Rather than an indecipherable and intimidating urban sprawl, Jonathan spun a story about flowing, cohesive, and nuanced community. Each piece he published felt not like an individual review, but a chapter in a greater narrative about the city, with each cook a fully realized character.

Later, when I became involved in a project called The Migrant Kitchen, Jonathan’s influence took on new significance. In a collaboration between Life & Thyme and KCET, the show was created as a observation of the city’s diverse influences as the culinary industry’s bedrock. The show felt like an extension of his work––and one it would have been very difficult to accomplish had he not already laid a foundation, done the exploration, and made the dining public aware of the dynamic global factors at play right on their dinner tables.

In his poignant writing, he could sum up centuries of history and a lifetime of culinary philosophy in a few lines, or through a single dish. About Chef Bryant Ng of Cassia in Santa Monica, whom we documented in the Season Two episode Beyond Pho, Jonathan wrote, “his pot-au-feu, [is] a statement of purpose written in carrots, broth and beef. …Ng, trained at the Cordon Bleu in Paris, is claiming the essence of French cooking as his own; colonizing the colonizers.” He asked that readers appreciate more than the ingredients on the plate, but the myriad factors that led to their confluence.

When his name came up in conversations with our subjects for the show, which is almost ubiquitously did, it was with reverence and gratitude. Not so much that Jonathan made their business––in the way that a three star New York Times review might do––but that he respected it. Patronized it. Loved it in a manner perhaps journalists weren’t expected or even permitted to. Jonathan became a part of these restaurant families; he was a beloved regular and a friend.

Jonathan restored the humanity to food criticism. He knew that to calculate a place based on the usual metrics––ingredient quality and ambiance, technique or service style––would be to leave the most important things on the table. That experience and adversity, love and intention should all carry equal, if not more weight.

Los Angeles is an imperfect and sometimes misunderstood city; its residents face enormous challenges regularly. It frequently hosts the transient, the impermanent––folks passing through for certain industries, taking what serves them before leaving it behind. But Jonathan’s work grounded its personality in the reliable and passionate people serving its food. Maybe they were newly minted Angelenos arriving from far flung corners of the world––a fresh and vibrant spice added to the city’s long simmering stew. Others may have been celebrating their businesses’ third or fourth decade––now an authentic and indisputable flavor steeped into the culinary landscape.

If we fortunate enough to see them emerge and follow in his footsteps, Jonathan’s legacy will be evident in generations of future food writers. His palate was singular, his perspective always thought provoking, his voice eminent. But his sensitivity and soul are what set him apart, and what brought the city together.

In a May, 2018 interview with Life & Thyme about the LA Food Bowl, Jonathan told writer Ziza Bauer, “My idea was to get people to live in their entire city. To get out of their neighborhoods, to realize the astonishing stuff was going on around them.” If we all remember to do that, we’ll not only honor his memory, we’ll make the world––the city of Los Angeles and far beyond––a more joyful, hospitable, and compassionate place to live. That he showed us we can do that through simple, honest food, is truly astonishing.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.