It’s a cool, misty morning on the Southern Italian island of Sicily when we’re treated to a love story. There are perhaps few cultures that love to spin a tale as much as the Italians—and Sicilians, for all their independence claiming and cultural quirks, are no different than their mainland brethren in that sense.

At first, it’s almost hard to listen though; the landscape is so distractingly gorgeous—a quilt of green tossed casually over the peaks and valleys of Mount Etna, each patch wrinkled with vines. Barbara Liuzzo, the co-owner of Barone Villagrande Winery, is giving us a hot tip on the future of this historic land, pointing to a structure in the distance.

“[We] decided to improve the winery with rooms,” says Liuzzo, referring to the agriturismo they’ve created for visitors at the winery. It’s a pretty exclusive booking—there are just four rooms. “I think in two years we will have other little accommodations,” she continues, grinning when she lets us in on a little something she plans to offer on the grounds: glamping. “Inside the little forest,” she tells us, pointing toward the dense thicket of trees. “Very luxury style,” she laughs, explaining there might be a few glamping options in Northern Italy, but not many here on the island.

Looking around at the three-hundred-year-old vineyard—Villagrande was established in 1727—the hyper modern notion of people wanting to fuse the rugged outdoors with the opulence of high-class accommodation seems incongruous. But one look at Liuzzo helps make sense of things. She’s chic and stylish, with the poise required of a woman in what is commonly a man’s domain. All this talk of style coupled with the sheer beauty of the scene before us actually feels entirely at home when you consider Liuzzo’s former life where she worked for Chanel in Milan selling luxury eyewear.

But Liuzzo’s modern sensibilities shouldn’t worry wine lovers who seek out Villagrande for its rich heritage—this is still very much an operation based on tradition. “My husband is the tenth generation of the winery,” Liuzzo tells us. “We have a son; we don’t want to press him, but he’s the eleventh,” she laughs. And whether or not they’re counting on him to keep the presses running and the grape juice in their bloodline, Liuzzo and her husband make it their life’s work at present.

The production—certified organic since 1989—takes place on eighteen hectares of land on the slopes of Mt. Etna, and the wines are a direct reflection of the territory, not only in the fruit, but in every part of the process and experience at Villagrande. When we turn and leave the view behind, dragging Deepi Ahluwalia, our photographer, away from the visuals that have captivated us all. Fortunately, she finds plenty of satisfying photo opportunities in our next location.

A steep stairwell is difficult to navigate, partly because it’s hard to take my eyes off of what is waiting for us at the bottom. Massive barrels, resting on their sides, looking like giant, medieval versions of what some trusty St. Bernard would wear around its neck had we been traversing the Italian Alps instead of descending into a time capsule of wine production.

The deep cellar was built in 1850, and was the first of its kind in Sicily. Actually, it was the barrels that were built first, with the cellar then constructed around it—it wouldn’t have been possible to transport the vessels down into the finished structure. The barrels are made from chestnut, an unusual choice for aging wine, but one unique to Etna.

“[Today] we don’t use them to age, because the wood is too old,” Liuzzo explains. “We prefer to use stainless steel tanks for fermentation.” Their whites are often aged in French oak, lending softer notes of vanilla, but chestnut wood is still used for the aging of many of their red wines—like Nerello Mascalese—following primary fermentation, strengthening the wine’s connection to the mountain itself.

“We produce territorial wine, so when you drink Villagrande, you taste the grapes of Villagrande, the wood of Villagrande, everything. We think chestnut is perfect for Nerello,” she says. “It’s very difficult to age wine in chestnut so a lot of people move to French oak. But I love chestnut because it’s very different.” The flavors from the wood are complex and moody—think dark cherry, or aged balsamic.

Chestnut also serves a function when it comes to the wine’s aesthetic. Many reds tend to fade during aging, but Liuzzo says using the darker wood “maintains the stability of the color year by year. [In the] Nerello, with the rich tannins of the chestnut, we maintain a ruby color even after ten years.”

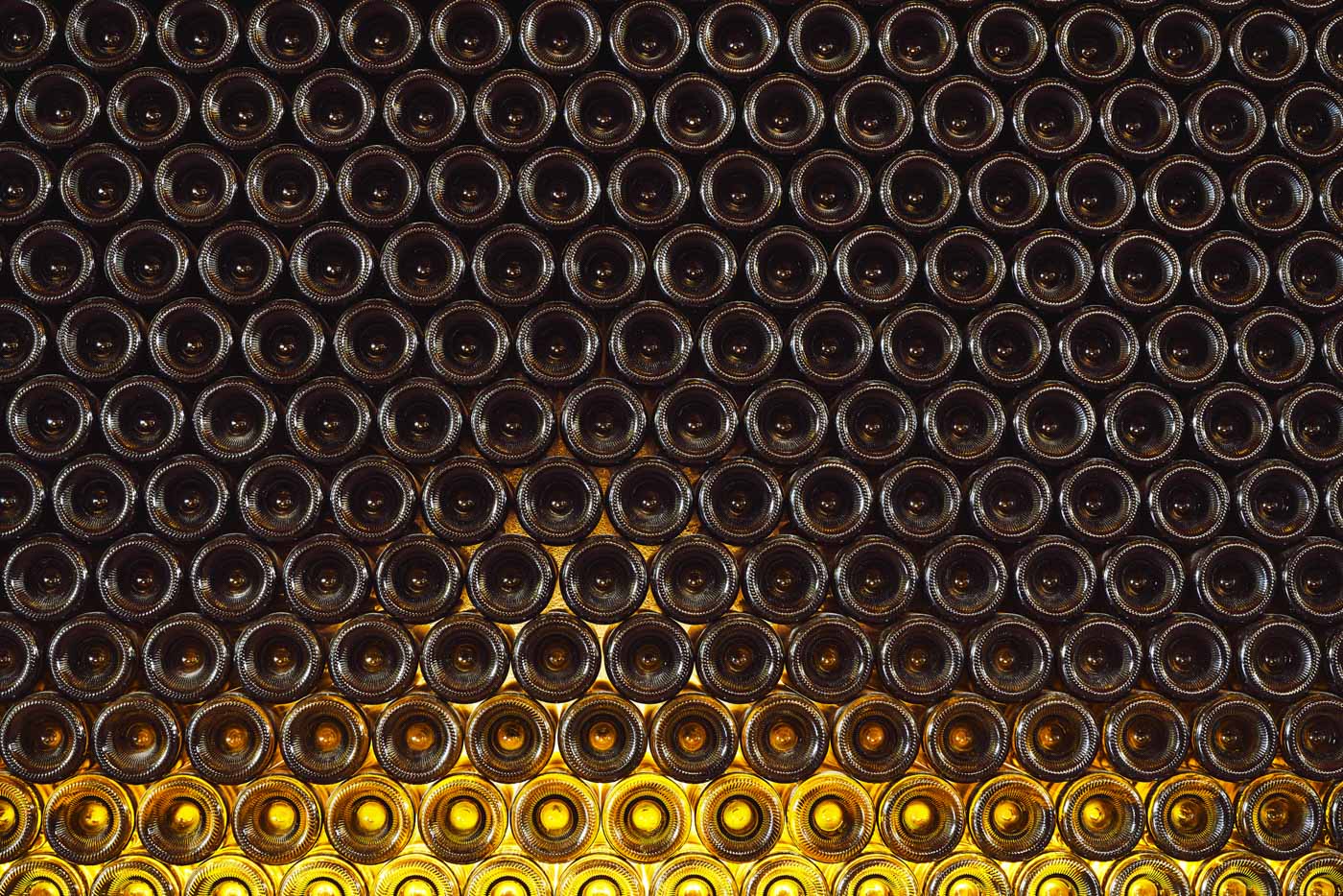

Like the winery itself, that endurance is a point of pride and emphasis for Villagrande. “It’s really important to give longevity and more life to the wine inside the bottle.” Even their white wines, the Etna Bianco made from ninety percent carricante, is uncommonly ageable. “Carricante can be tasted very fresh, after about one year in the bottle. But it’s also wonderful in five or six years, and a maximum would be about ten years.”

Liuzzo and the team taste their vintages regularly, giving them important insight into the durability of the wines. “We have very important bottles inside the cellar. We taste wines from forties, fifties, sixties, to understand what happens year by year, and the potential of the wine.” Benefiting from a long history, Villagrande has perspective on change over the years, whether that’s climate or style, or attention paid by the winemakers of the day.

That’s not to say that every era has put the same kind of care into the operation. “Generation over generation, maybe one [has been] involved, one [has] not,” Liuzzo muses. “When the winery arrived to us, we understood we had to give to the winery our [own] idea, but it was very hard; there was a lot of work to be done. We decided to put everything into the winery. It’s our life, completely,” she tells us, entirely at home in the depths of the cellar and the history that is central to Villagrande.

The subterranean room is impressive and that history is palpable—in the aroma of centuries of fermentation, in the craggy, weathered chestnut wood, the uneven floor that one can only imagine has seen hundreds of pairs of boots. But two small rows of pristine French oak—for that Etna Bianco—also flank the rear. If someone had stumbled down here without the benefit of our guide, those modern oak barrels would indicate this operation is very much an active one.

When we ascend to the surface, on to the tasting portion of the visit, Liuzzo stops to speak to some passing workers in rapid fire Italian punctuated by big smiles and laughter at jokes we’ll never be in on. But there’s good humor all around this place, that much is clear. Liuzzo leads us into their tasting area, which reminds me of some scene from a beautifully designed period piece. Maybe something from Beauty and the Beast. Exposed beams strap tall ceilings, and the entire room is awash with natural light from wide windows overlooking the vineyard, where the mist is burning off a bit. We take a seat at a long farmhouse table, and the potent aroma of spicy, fresh olive oil precedes the delivery of a bowl of the emerald liquid (Sicilian, of course), and house-baked bread.

I had intended to ask Liuzzo what made her take leave of the fashion world for this life, but looking around, it’s hard to imagine why not. “When I was younger, I always dreamed of having a resort with a winery,” she tells us, passing the bread around the table before taking a slice for herself. “So it’s completely crazy!”

Liuzzo did grow up on the island, but left to pursue her career in the fashion world, not in winemaking or agriturismo management, despite that dream. But like so many Italians, she followed passion and romance back home. She’d been visiting Sicily when she boarded a plane back to Milan. A fellow passenger named Marco Nicolosi was having difficulty with his carry-on: he was trying to transport a case of wine—twelve bottles—when the per person maximum was six. The flight attendant turned to Liuzzo, “Would you take the other six bottles and say they’re yours?” he asked her. “I said, ‘Okay, but I want one!’” She laughs. Nicolosi made good on the request, and then some—the two shared more than a few bottles of wine over the years since they eventually married.

“I really fell in love with Etna as much as my husband,” she laughs. “I had a very important job, but I decided to change my life,” she says of the decision to return to Sicily with Nicolosi, where he ran his family’s winery, for the sake of love and the liquid they’d come to produce together.

At Villagrande, that love also comes through in care for food, pairing, employees, and every aspect of what makes the place tick. Liuzzo seems just as inspired by the sun-dried tomatoes and crusty bread as she is the grapes outside, and we all geek out over our favorite fresh vegetables like we’re old friends having an afternoon break together.

As part of our tasting, we’re served a honey that comes from apiaries in the forest surrounding Villagrande, run by one of their employees, and wild fennel that sprouts in the vineyard. She describes a bruschetta made with tomatoes that grow in their organic garden, basil and other aromatic herbs from the winery. The pairings they serve highlight the wine, but the terroir of Etna is a comprehensive gastronomic experience. Although Liuzzo is much too down-to-earth to ever describe it as such. This is just the way of life here on the volcano.

The evolution of the Etna wine industry has ramped up considerably in the past decade or so. That development can be viewed through the lens of Villagrande, as a producer who has been operating long before the new wave of wineries began bottling their products. “We are a very old winery. Maybe we were unique before, and it was very difficult to become popular with only two or three wineries in your region without a lot of money for advertising,” she says of the years before the Etna boom.

Now, the wine industry here has become foundational to the residents’ lives. “It’s very important [to the economy of the area],” she tells us. “I think in twenty years, Etna will be like Brunello. The region is very special for wine production. Etna was the first DOC in Sicily in 1968. [Later], investors saw the opportunity to not only create a product, but invest in advertising for the Etna area wines.” Investors, she says, began sinking money into communication and marketing, and those dollars made a difference for the entire region, which was lesser known thanks to its limited scope and output. “It’s an original place for wine production, but very small and very difficult for people to discover.”

To an American like myself, her business has an almost incomprehensible history, and yet Liuzzo’s attitude toward the sudden surge of new wineries in her territory is not one of competition. “My opinion is if they work well, if they respect the region of Etna, they are welcome,” she says, adding that the preservation of the DOC is paramount to the collective industry.

Sicily produces so many products specific to the island—ones that rely on tradition and technique passed down—and as aging generations have thinned, there has been concern that the area’s heritage products will die out. “When you have the passage of generations, it’s always difficult. The winery has seen everything. Earthquakes, war,” Liuzzo says.

Each bottle reflects the narrative of its producers, the region, and world around it. As the wine industry globally contends with challenges like climate change, these bottles are not only a window into an individual winery, but evidence of a changing world, one into which Villagrande has special insight given its age and in its location.

“We are very influenced by the climates and microclimates on Etna. We have rain, we have wind coming from the Mediterranean, we have volcanic soil and different temperatures between night and day,” she says. “If we have a lot of rain and not too much sun, it’s very difficult. We have the wind from the sea to dry the grapes, so we don’t have mold. But if it’s very rainy, we can lose a lot of grapes.”

Conversely to other wine producers, the rising temperatures have been advantageous in some cases. “We have more sun [as a result of climate change], so for us it’s [been] a good change.” She recognizes, however, that many fellow producers are suffering damaging effects. “In Sicily, it’s a problem; [we’ve seen] other wineries on the coast lose about thirty percent of the production because it was too hot.” She goes on that in 2017, the rain that many rely on being consistent was unusually low, which caused a significant loss of harvest for some growers.

This kind of change raises questions beyond whether they’ll have the bottles to serve in their tasting rooms or sell to distributors, but may require more sweeping changes in terms of what is actually produced, not just how much.

“The wine world is still very young,” says the woman at the helm of a three-hundred-year old winery. “The territories [may be] historical, but now we are starting to understand the regions and the particularities. For many years we were just committed to understanding merlot in Etna, or cabernet in Montalcino. But why?” Liuzzo questions the decision on the part of the humans involved here to determine what should grow where, suggesting it should be the other way around. “There are so many varieties. All wine production areas have to understand what is best to have in [their] region. We all have to improve in this way. We have to let the land decide.”

That experimentation is critical to the wine industry all over the world, as temperatures and precipitation levels change, wine producers may not have the luxury of continuing to grow the same grapes that they’ve always been known for, or that their customers have come to expect. The old world, European growers with legacies and expectations, may see themselves taking cues from regions with more freedom to explore. “Napa Valley is a very young place of production, and so they experiment without chains,” she muses.

The terroir of Etna wines are especially unique thanks to the volcanic soil and activity of the volcano. “For the grapes it’s a dream. We have black rain, which is when we have little rocks coming from [a volcanic] explosion, and it helps the fertilization of the soil. The black rain has many nutrients.” The summer, she says, is an especially active time for Etna.

“The price is always high in Etna wines because production is high and we do everything by hand. So usually Etna is expensive.” She means that both in cost, as well as what’s at stake. “We are used to living with the volcano, but when we have big eruptions we still get afraid. We risk many things.”

Fortunately for wine-drinkers, there are still people like Liuzzo and Nicolosi who will take that leap of faith, and lead by example for future winemakers. “The youngest generation is passionate; they understand the importance of the region and they’re investing in it. The north side of Etna fifteen years ago was completely abandoned,” Liuzzo says. “Now you see vineyards, wineries—it’s a real renaissance.”

If history has shown us anything, it’s that an Italian renaissance—of all art forms, shapes and sizes—has been known to change the world.

A Starter Guide to Barone di Villagrande Wines

Etna Bianco Superiore

Etna Bianco is made with ninety percent carricante grapes; it’s floral and honeyed, with a crisp finish. “I love the freshness,” Liuzzo says. “You can pair this with anything. It’s very easy to drink,” she says, although it is especially recommended for shellfish or crudo.

Etna Rosso

Villagrande’s red selection is eighty percent Nerello Mascalese, twenty percent Nerello Cappuccio and Nerello Mantellato. Liuzzo explains the minerality of the wine. “It’s very dry because of the soil, the rain, the climate.” It’s an elegant wine, and the chestnut makes a distinctive appearance in the flavor. She suggests a pairing with tuna, bluefish, or, for vegetarian or vegan selection, the Sicilian specialty dish, caponata.

Etna Rosato, 2017

“We press the wine and remove the skin immediately. There’s no maceration, so the wine is very light,” Liuzzo tells us. Made with ninety percent Nerello Mascalese and ten percent carricante, the pink wine has the look and feel of a Sicilian sunset, which is exactly when I’d like to be drinking it. The folks at Villagrande recommend this wine as an aperitivo, or with first courses. “We love to pair the rose with a Sicilian bruschetta with basil or sun dried tomatoes, because it’s very dry and flavorful,” Liuzzo says, adding a nod to the hip rosé all day stateside trend. “We sold a lot of rosé in New York. A lot.”

Malvasia

This dessert wine, with herbaceous notes and a nod to golden raisins, is something I could easily drink all day—but maybe that’s my sweet tooth talking. It’s a perfect after-dinner drink or paired with cheese; but it’s also a unique wine that could easily stand on its own. Perhaps that’s in part because of its upbringing, produced independent of the main Villagrande property in super small batches. “We have another very small winery, just two hectares on Salina Island,” Liuzzo tells. “It’s made with a special, ancient process. We pick up the grapes at the beginning of September and put them on the roof of the winery in a single row, and sun dry these grapes for about twenty days.” During that time, the grapes are covered at dusk and uncovered at five a.m. to protect from overnight humidity. “In this period, we lose the excess water and maintain just a sweet juice. You have the flavors of the sun.”

This story was made possible with the support and collaboration of La Cook.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.