Editor’s Note: Katie Bell served as the Opening Director of Operations for 232 Bleecker, which opened its doors in New York City’s West Village on December 16.

One of my biggest personal changes in the past few weeks is the discovery of the thing so many other people seem to have, something they exercise when they come dine with us and linger over a leisurely meal: time.

In this new world—the one defined by COVID-19—I find myself constantly lost for words. I can repost, I can sign petitions, I can call representatives, I can organize, I can get on calls, I can cook for my neighbors. But to speak about my experience—that’s hard. And I keep putting it in a box, right alongside cleaning out my bathroom cabinet and baking bread. I will do those things tomorrow. I will contemplate tomorrow. I will investigate tomorrow. I will find a way out tomorrow.

As anyone who has experienced this work knows, coming out of a restaurant opening, time is a coveted commodity. We steal moments with our loved ones when we can get them on a Tuesday morning or when they stop by before service on a Sunday. We generally don’t stay home and cook with family or friends—more often than not our most nourishing moment of the day is family meal, sitting with our team, eating out of a quart container.

There is time now.

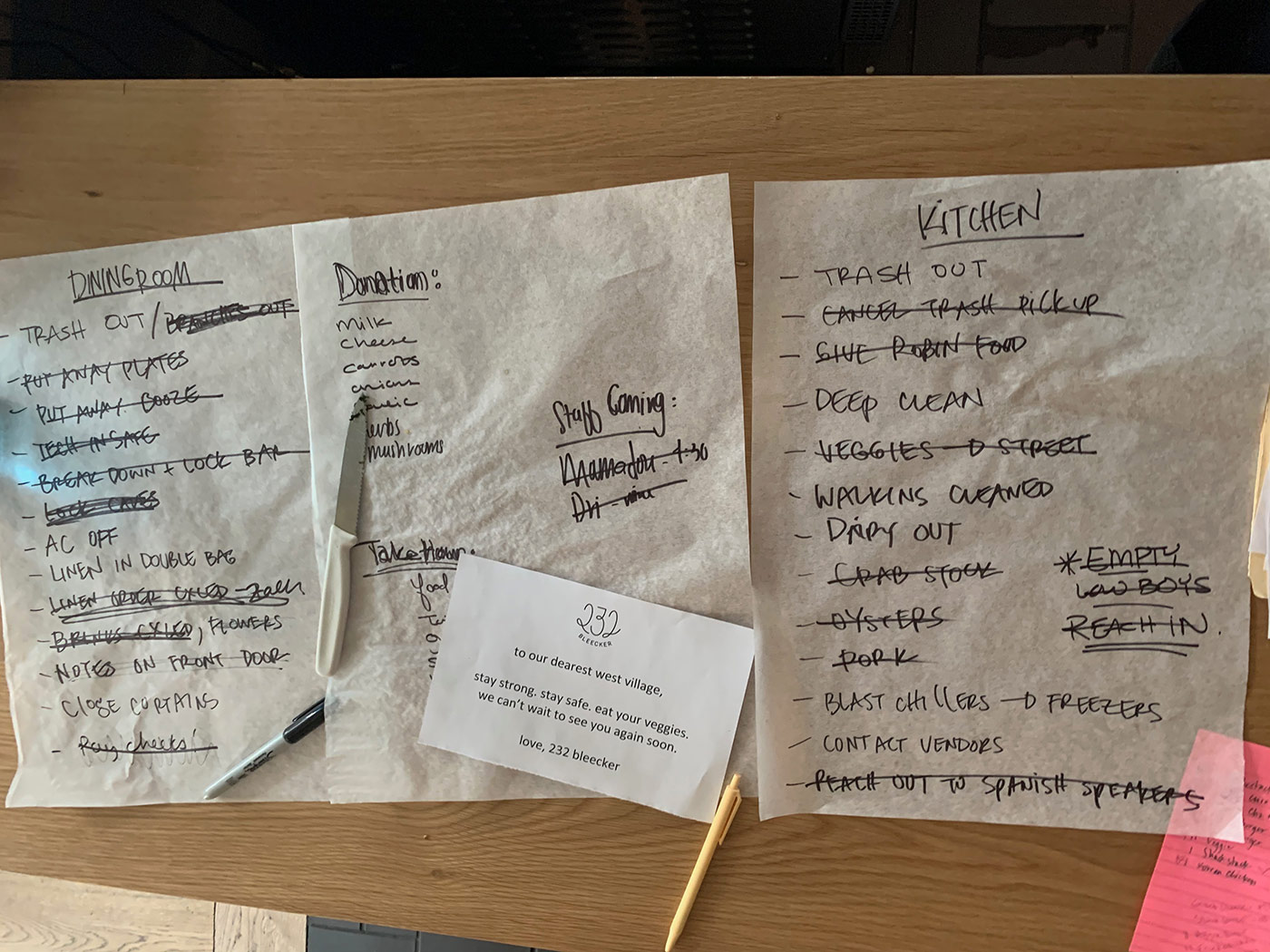

Before 232 Bleecker shut down, I had taken exactly three days off since the opening of our little restaurant. Seven-day-week after seven-day-week bled into one another as the team gently and firmly, easily and through tears, in howling laughter and in expletive-laden frustration, built a restaurant and a community in our little corner of the universe.

When we began to see the impact of what would soon be called a pandemic in New York City, we were two weeks from opening for lunch and brunch. We already hired and trained staff. Pushing it back seemed impossible and we fought in phone calls to move forward with the plan. We’d be slow, maybe, but we wanted to do it for the team and for the neighborhood. The following day, as business suddenly slowed overnight, we acquiesced to pushing lunch, but agreed to move forward with brunch. The day after that, with business dropping further and the news beginning to talk of quarantines and social distancing, we unanimously agreed there was no chance we were opening for brunch service. Instead, we began discussing take-out—something we’d been saying for months we would never do, but it suddenly seemed like what the neighborhood needed.

The next day, we launched the take-out operation and were subsequently mandated by the state to remove fifty percent of our tables. We complied, and also began packing bags of fresh vegetables to send home with each guest after their meal. We started offering farm boxes of vegetables for take-out as well, a nod to the increasing cooking at home we saw on the horizon.

We were starting to see neighbors and friends from the industry dining out after closing their restaurants, or having been furloughed or laid off. In a matter of two nights, the air went from mildly buoyant—that famous New Yorker brave face, the resilience that has gotten this determined and gritty city through so many hard times—to a tangible grief. There was a lot of solemn gratitude. Guests were grateful for a well-spaced seat, a warm meal, smiles, and being welcomed in by gloved hands. And we were so grateful for every single person who chose to support and dine with us. It was a confirmation of our decision to stay open, one we were actively making each day.

At that time, we were running with the slimmest crew we could in order to ensure as few of our team members as possible take public transportation, so those working in the dining room would make the most money under the circumstances. Even with half the tables gone, we were busy. It felt like most exchanges I had with my team were over the tiny hand-sink in our dish station, scrubbing my raw hands after each table I cleared, each glass I removed, each napkin I grabbed off a chair. I stood with friends and neighbors, introduced myself to restaurant owners and tourists. Each conversation was direct and heartfelt. I made new friends and deepened friendships in those last days, standing a little farther from guests in our now unfamiliar dining room.

However, as news continued to pour in and we all became increasingly aware of the spread and strength of the virus in our city and our country, things started to shift. Suddenly, seeing four people standing at the front of the restaurant felt irresponsible. Suddenly, two tables seated next to each other in our new, spaced out dining room, still felt too close. Suddenly, we were discussing closing the restaurant, switching to a take-out only model—an unthinkable idea just a week before.

The questions in front of us changed with the reality of each new day, and were completely different from what we had tackled the day before. We spent days trying to determine what was “right.” Keeping our team employed and paid felt right, until keeping our team and guests healthy and safe felt more right. There was no correct answer, and the rules kept changing.

The following day, after a series of phone calls that decided we should close the restaurant for the safety of our team and our guests, we emerged from the office around 9 p.m. to share heartbreaking news with the management team. Coincidentally, moments earlier, the news had broken that the state decided to close all restaurants, bars and theatres. Once again, a difficult and tenuous decision was inevitable just moments later as once again, the rules changed completely.

We gathered the dining room managers and sous chefs around the prep table in the basement kitchen, which had just been sanitized for the fortieth time that day. We sat on stools and crates drinking nice champagne and a bottle of whiskey a chef had given us a few weeks ago, back when life was normal. Back when we hadn’t ever considered things like being told to remove half our tables, or to close our doors. Back when the word “mandated” referred to patio seating and music playing and alcohol service on Sundays. No one was speaking about the future or pretending to have any idea of what was coming next. No one was eloquent or even encouraging. We just sat and drank and enjoyed one another’s company.

Looking back, I think we were in shock. We weren’t thinking about the next steps or even about how much we would soon miss sitting around a prep table drinking out of pint containers. I certainly wasn’t; I was just feeling a slight sense of relief, to have a pause after days stacked with heart-wrenching decisions and fraught conversations.

It was a moment to breathe after days of bated breath. After services with a team who—normally hilarious and joyful—were almost unrecognizable with tension and concern.

When we closed our doors on March 16, we had been open three months to the day. And while the decision to close eased some of those stresses, it opened the floodgates to others—unemployment, financial concerns, a business closed early in its fledgling state, and the stress of the unknown.

I’ve been working in this business for over twenty years. Nearly everyone I know and love is also in this industry, and every friend and family member of mine who works in hospitality is now in one of two camps. Half are laid off or furloughed (a term no restaurant person knew before this crisis), or if very lucky, they’re on a reduced salary. These are talented people who have worked, in some cases, for decades to hone their skills, build their reputations, find the restaurants and chefs to dedicate themselves to, and they are now without work. They’re learning to file for unemployment. They—and I—are considering what reemployment looks like after this. Who will reopen? How many will reopen with a full staff? How will we financially survive the months before we begin to see reopenings? How will we survive the months of reduced capacity after opening?

The other half are business owners—many are award-winning, highly successful restaurateurs and chefs. A couple months ago, our conversations were all about the staffing crisis. Now, in a matter of days, instead of looking for hungry new talent, they were forced to lay off teams they fought for and worked to build, maintain, inspire, and keep engaged. Because restaurant margins will never—no matter how big or fancy or award-winning—be able to cover payroll without revenue. They dropped off bags of vegetables and eggs and butter from their now empty restaurant walk-ins along with final paychecks for their cooks, servers, dishwashers and managers—something none of us would have considered a possibility just a couple months earlier.

It’s impossible to describe the feeling we’ve all had as we’ve lost jobs or delivered the news of lost jobs, weighed our team’s and guest’s safety, weighed our own safety and health, and debated the risks and rewards of one more paycheck. We’ve adapted the way we always have; but this time, instead of subbing ingredients in a dish at a diner’s request, it means pivoting to take-out and delivery, pivoting to a new job, to volunteering, and to all of us wondering what to do next.

As we went home the night we closed and the dust began to settle, and we began to see a little farther than a few hours in front of us for the first time in months, we began to do what we always do. We try. We try to feed people. We try to support our teams and our fellow restaurants. We try to support and feed those without pantries, those without homes, those without jobs, those working in hospitals and fire departments and police stations. We share petitions, campaigns and information. We join coalitions and alliances, and share spreadsheets of resources. We volunteer—my team pitching at farmers markets, delivering gloves to hospitals, and cooking for soup kitchens. In hurricanes, we’ve cooked and served. In blackouts, we’ve cooked and served. This disaster is no different. People need to eat. People need food.

We’re not used to helping from home or from behind a screen. We are people who use our hands. It’s heartening to see so many incredible people lifting up exhausted heads and trying to find—or invent—ways to help. I am speaking with friends each day who debate over and over again whether they should be going out and helping, or those who are out there, whether they should be going out and helping. Our compulsion, our skill, and what makes us good at our work, is to be community builders and hands-on helpers. And for the first time in our lives, that is a fraught, and in some cases, entirely restricted offering.

When we lost Chef Floyd Cardoz—the trailblazing chef of Tabla, Paowalla and Bombay Bread Bar—to COVID-19 on March 25, it was another layer of this crisis. We were already mourning lost restaurants and jobs. Losing our people, our mentors and our friends, is a consequence that hadn’t quite struck home for many just yet.

So I pause, and I pray. It’s at least something to do with my hands.

Opportunities to help are out there. Here are some of the people doing important work and ways to support them financially, if you are able; by volunteering, if you are able; or by sharing their work and sending good wishes.

——

World Central Kitchen: I am always in awe of the work WCK does to bring hot meals to communities in need and the grace and logistics they bring to the massive, important work they do. They are doing even more massive work today supporting those who are hungry in these scary times. Donate here.

God’s Love We Deliver: God’s Love delivers hot meals for housebound people with serious illnesses who are unable to cook for themselves in New York City. They are a pragmatic and joyful organization doing vital work. Donate here.

Hospitals, Farmers, and Local Soup Kitchens:

Hospitals are in need of plastic gloves and N95 masks. Farmers are in need of bleach and gloves. If your restaurant or business has even a small inventory of these items, please consider donating them to organizations in need in order to keep those working the frontlines safe and protected. All hospitals, farmer’s markets, and God’s Love We Deliver are taking donations directly.

Reach out to me at @katiebell on Instagram to connect with farmers for donations of bleach and supplies or to find out more about how to support our farmers and producers in these hard times.

For the future of restaurants:

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.