Discovering Strength in Ancestral Spirit with Tiffanie Barriere

A dedication to historical research has helped power cocktail educator and consultant Tiffanie Barriere in the modern moment.

Editor’s Note: This story is published in The Reboot Issue of Life & Thyme Post, our exclusive newspaper for Life & Thyme members. Get your copy.

Jupiter Evans was a gift.

The man, who was born in Virginia in the mid-eighteenth century and destined to make a mark on the American tradition of cider-making, is little known by name today. But Evans was gifted to a figure with a far more commonly known name in American history— Thomas Jefferson—on his twenty-first birthday.

“Happy birthday, son. Here’s your own slave,” Tiffanie Barriere says, recounting the story of how Jefferson’s father, Peter Jefferson, owned the Evans family and granted his son with ownership of Jupiter.

Of Jefferson himself, Barriere says, “He was quite the party guy, and one of his favorite things to sip on was cider.” And so one of the tasks Evans assumed was that of creating the drink for the future founding father. “Jupiter Evans was [Jefferson’s] number one slave. [Evans] was that dude, making that cider,” Barriere explains. She goes on to describe the cider-making process, the importance of cider to American history, as well as a great deal about Jefferson’s personal history with slave ownership, and his relationship with Evans in general. And this is just one of the stories she shares with me during our brief conversation.

Barriere has made a career as an award-winning cocktail consultant and educator; she’s a member of the Tales of The Cocktail Grants Committee and James Beard Beverage Advisory Board. And I’ve been following Barriere’s Instagram (@thedrinkingcoach) for some time, taking in her bite-sized history lessons, which she serves alongside cocktail tips and recipes like a bowl of salty bar nuts—addictive, nutritious, and perfectly complementary.

Her stories, like that of Graman Quassi, for example, wouldn’t likely be found on the history shelves in any library though. The accounts of individuals she features, like Evans, have often evanesced. “Graman Quassi was a freed slave, born in West Africa in 1690. Quassi was a healer, botanist, slave, and later freedman who is today best known for having given his name to the plant genus [quassia],” Barriere’s post reads, before listing the ingredients of a Trinidad sour—Angostura bitters, lemon, orgeat and rum—in his honor. “This cocktail is for the ancestors, healers and [botanists] who cured many lives while fighting for their own.”

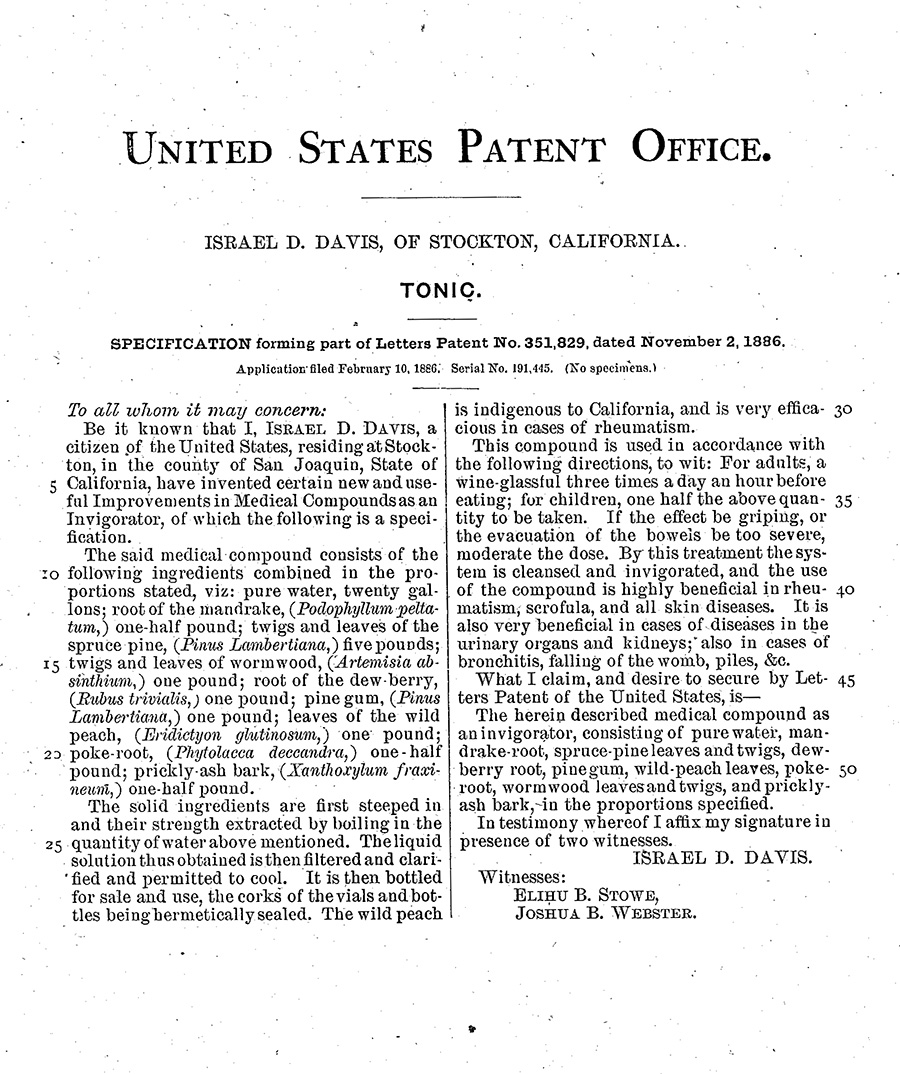

Another drink, which Barriere calls “On the Mend,” includes turmeric, ginger, fig syrup, tequila and tonic water, and celebrates the life of Israel Davis, who Barriere writes was an African American man from Stockton, California, who in November of 1886, submitted his patent application of tonic, “a carbonated soft drink flavored with quinine.”

Graman Quassi was a healer, botanist, and former slave in the eighteenth century. He is known for giving his name to the plant genus quassia. This illustration, “The Celebrated Graman Quacy,” was by the painter William Blake (1757-1827).

But beyond the delicious drinks and fascinating content, it’s the way she relays these stories—with exquisite detail, vivid description, and palpable excitement—that makes her work as an anthropologist so impactful. With Davis, she continues that, “Not much is documented on [his] life, however his flavors along with a need to produce a tonic for healing with a fruit finish was magical.”

Barriere prefers to teach this way—with love and passion incorporated into each lesson plan—because she believes it’s how people best learn. “My approach to teaching is almost like CliffsNotes. Let’s drop some history, let’s go past, let’s go present, let’s go flavor, let’s go love. Boom,” she tells me, beating out every element as if she’s sharing a cocktail recipe.

In recent years, as a culture we have begun to revisit history in an attempt to recognize individuals who have been erased from the narrative, and I have frequently found myself wondering who is behind the research, doing the painstaking and difficult work of discovery when so many have egregiously been omitted from our national records.

It requires not just a curious mind, but a dedicated and tenacious spirit. Barriere clearly has those inherent qualities in abundance, but her motivation goes beyond, to a personal history, being raised Black in America. “Being Black, we have our own Black history,” she tells me. “You learn American history at school, and then you learn Black history at church or at home, or just by word of mouth—your parents or grandparents tell you.”

But Barriere wasn’t satisfied with what she’d been taught over the years, leading her to pursue her own detailed and diligent study. When we speak, she describes her exhaustive process. “I get deep in a rabbit hole,” she says. She explains that she begins her research with contextual elements like era and location, the sitting president, and whether there was a war or other notable event in the moment. Given the patterns of history, Barriere says she can usually count on one fact: “Obviously, there’s a slave. If I can get some names from the white side, then I dig into ownership.” From there, she attempts to uncover the narrative. “You’ve just got to dig,” she says.

Barriere hopes to pass along the deep satisfaction of her discoveries. “I nerd out on all kinds of history. In the past ten years, any time I’m serving, you’re going to get that from me,” she says. “Make it interesting; make it really fun. It’s like teaching a kid to read—read something fun, read the comics, you’ll get it. I think that helps get knowledge out.”

Tom Bullock was the first African-American author to publish a cocktail manual, The Ideal Bartender. Bullock was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1872 and was a bartender at the Pendennis Club, the Kenton Club, and the St. Louis Country Club.

In 2020, Barriere has had to adjust her approach. No longer being able to connect with drinkers in person, she’s focused on new ways to engage with her followers, whether through virtual cocktail classes or by offering cocktail kits for those in her local community.

These creative solutions perpetuate the work in which she believes so strongly, educating and providing context to human stories erased from our history. They also serve a more practical function, to combat the challenges facing so many in the service industry as a result of COVID-19 restaurant and bar closures. “I’m scared as shit,” she tells me. “I didn’t get any unemployment, I didn’t get any business loans—I didn’t get anything. I’ve just been winging it. I’m digging a hole and tossing in a drop of water at a time.”

She describes the ways in which daily life has been a learning experience this year, constantly trying to meet the needs of the moment, be it personally or professionally. And now, when it feels as if history is being made every day, Barriere—who identifies as a Black, queer woman—is being called upon to provide a different kind of lesson. “My industry was looking at me, first and foremost, to Black Lives Matter. They’re like, ‘Oh my god, I never thought about it this way with you,’ and I found myself getting angry,” she tells me, explaining the ways in which those conversations led to her modifying her own behavior. “I’ve never dropped my Black card. I’ve never dropped my gay card, and now that I have to, it has defintely been a shift in the way I communicate, the way I post, the way I teach, the way I send an invoice, the way I stick my chest out a little bit.”

The shift in communication is compounded when put into the context of her professional platform as well. Barriere is experiencing a new feeling of responsibility, having to reposition not only for purposes of financial resilience and job security, but social impact as well. “Now I have to be other things. And nothing is wrong with it, but it definitely puts a little more weight on my presence and platform,” she says.

While her work has long been focused on updating the narrative regarding injustices of the past, she’s now focused on ensuring the story of the moment is acknowledged, and that the nuance of the human experience isn’t lost. “When Pride started, I didn’t really feel the need to focus on my queerness; I was still focused on being Black,” she says. “A few years ago, that would be like, I’m a trifecta: I’m Black, I’m queer, and I’m a woman. And now it’s like, fuck, I have to fight.”

But being assertive, Barriere says, isn’t in her nature. “That’s been bothering me because I’m the approachable, sweet, cute, fun, it’s-all-good girl,” she says. “I’m quite soft spoken when I’m around people who want to dismantle things. I’m super organic. I tell my therapist I think I’m almost too soft, too chill. I don’t fight—until two or three months ago.”

This moment has been one in which she has had to reevaluate, and also reconcile with how she presents herself. “I felt like I was being pushed. I had people sliding into my DMs who had been friends or followers for a while wanting to, I guess, ally or say, ‘I’m here with you,’ or, ‘I’m not that person,’” she says. “And I’m like yeah, I get it, but right now we’re in triple mourning. The ancestors have awakened.”

Barriere has, however, been encouraged by new standards that she feels signify social progress, like shifting views on gender representation. “I do like the fact that we have to introduce ourselves with pronouns,” she says, and credits up-and-coming generations with pushing forward. “The elders that we grew up following and watching never spoke about sexuality or what they did; they just were good at work,” she says. Barriere, who recently celebrated her fortieth birthday, says her generation focused more on how to “just make it by and be proud of what we do. And then the kids [after] us are like, ‘No, say it loud. You’re gay and proud, you’re Black and proud,’ and you’ve got to. I do love this new [idea, to] identify who you are, represent it so people can speak and treat you differently.”

Visibility and representation are twin engines that have long helped power social battles, and for Barriere, this year has drawn attention to the significance of sharing identity. “Not a lot of people knew that I was queer. I’m comfortable now with people knowing all of who I am, along with, ‘she can make a badass drink,’” she says. “I’m happy to see my industry be comfortable with who they are. I deserve a space because I am who I am.”

And while evolving perspectives have been inspiring to her in looking ahead, Barriere’s work and passion are still rooted in history. The gravity of social responsibility hasn’t dampened the enthusiasm for her work; in fact, it has validated its importance. “I love telling those stories because a lot of them are not shared. Of course, they never documented us at that time; we aren’t documented as much now,” Barriere says. “But when we are documented, the interviewer is always wowed by the naturalness of what we do as Black or people of color.”

A copy of the original United States patent for tonic in which “the system is cleansed and invigorated, and the use of

the compound is highly beneficial in rheumatism, scrofula, and all skin diseases.” The patent was filed in 1886 by Israel D. Davis of Stockton, California.

Barriere shares her own sense of awe, which bolsters her passion for bringing to light the stories of individuals who have been erased; in their resilience, she finds a blueprint for modern struggle. She finds moments in social media to celebrate that strength. On Mint Julep Day this year, she shared a toast via Instagram to the “surprising number of Black mixologists who made enough of a mark. Black bartenders across the South made the Mint Julep a national sensation and, in the process, invented modern mixology,” including, “Cato Alexander, Osaamus Willard, William Niblo, Peter Bent Brigham, John Dabney, Tom Bullock, Ms. Martha King Niblo and many more who never had their name written, yet stood respectfully at the bar.”

Continued discovery keeps her curiosity engaged. “There’s something about slavery and service that has me very intrigued,” she says. “As horrible as the story was, I find that the way they looked, the way they acted, the way they stood and how they served—was just crazy! Knowing how long to steep tea, how to stretch it if they ran out, knowing how to make a cocktail, knowing how to make the perfect lemonade and what kind of sugar and honey.” Barriere is astounded by the inherent knowledge, found somewhere within, to address what was being asked for, because, “for one, [slave owners] don’t know how to. And second, because you just figure it out or else. You will get beaten or raped or killed.”

“The [mentality] of the ancestor has me excited to share their story,” she says.

As an educator, Barriere knows that the value of studying what came before—beyond that it can make for damn good storytelling—is to find strength and answers for the present. When it comes to the future, Barriere will be doubling down on the past. “Now, more things are being discovered,” she tells me, sounding like she is ready to hit the library as soon as we’re off the phone. I’m curious what’s next on her research list, and what she’s most excited to learn next—and her answer couldn’t have been more intriguing to this whiskey lover. “There’s no way in hell American whiskey is being created during slavery, and we’re not going to talk about these Black guys? Something is missing,” she says.

“We just want to know their names.”

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.