Editor’s Note: This story can also be found in the Fall 2020 issue of Life & Thyme Post, our quarterly newspaper exclusively for members. Get your copy.

For forty years, the Community Alliance with Family Farmers (CAFF), a California-based nonprofit, has sought to support and advocate for family farms, regenerative agriculture, and local food systems. But no amount of experience could have fully prepared the organization or its members for the first nine months of this year.

In August, Evan Wiig, director of membership and communications at CAFF, described the impossibility of a pivot for one of the organization’s members, a lettuce farmer in the Sacramento area.

After COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders went into effect, schools closed, and the contracts this particular farmer had negotiated with local school cafeterias fell through. “We’re talking six or seven acres of just lettuce, ready to harvest and send out to schools the following morning,” Wiig says.

“The one thing I think is important for folks to understand—especially those who might not be immersed in agriculture—is that one of the things that really makes agriculture uniquely vulnerable is we’re entirely time-bound,” Wiig explains.

While certain crops, like squash or potatoes, might be slightly more forgiving in terms of time from harvest to market, many crops—especially leafy greens—are highly time-sensitive.

“Imagine, you’ve got lettuce that’s perishable and you have twenty-four hours to find a market for six or seven acres of lettuce. You can’t do that,” says Wiig. “For a lot of these crops, you have hours, days—weeks, if you’re lucky—to find a new market. Those farmers were literally on their tractor crying as they plowed that lettuce back into the ground.”

Every industry has been impacted by COVID-19, but the hardships suffered by farm owners and farmworkers are unique, even within the food industry. While many businesses can turn off the lights, close their door and transition online, agriculture is characterized by immutable physical and temporal constraints that move onward at the unrelenting, indifferent speed of nature.

For farmers, Wiig says, “You have to plan out a year in advance for sowing the seeds, for tending to the crops, for harvesting the crops, and then getting them to market.”

While the market disruption caused by the pandemic may be unprecedented in its scope, unfortunately farmers are all too familiar with the precarious reality of their line of work. Talk to any farmer and you will find the milestones of their lives are marked by traumatic weather events.

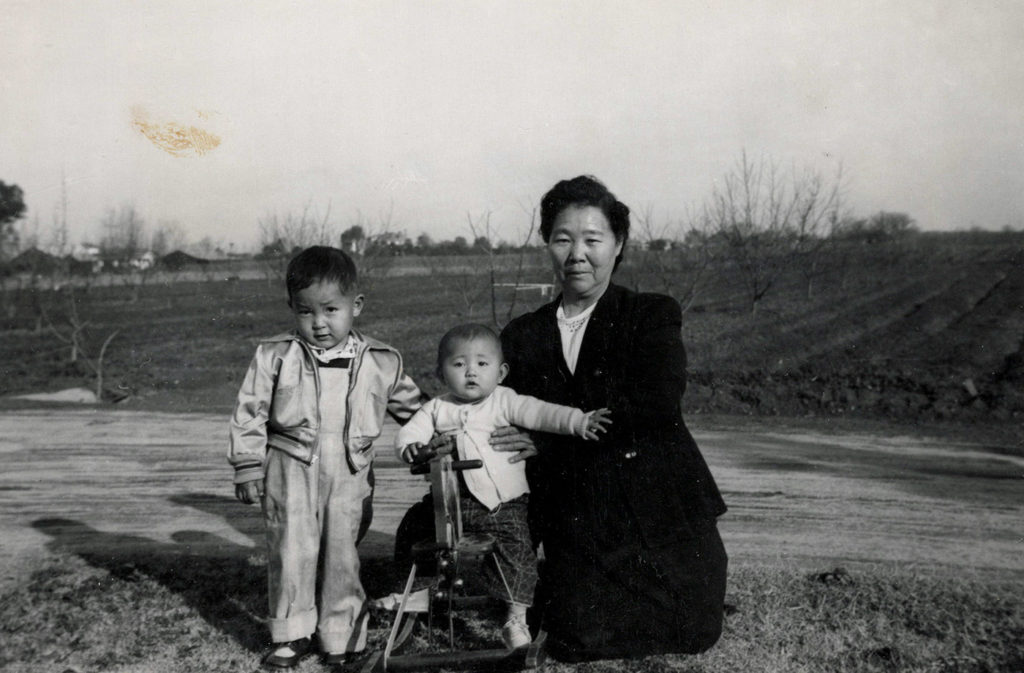

“I was nine years old, and in seven minutes we lost ninety percent of our harvest for that year. Seven minutes of hail,” says Nikiko Masumoto, a fourth-generation farmer at Masumoto Family Farm in Del Rey, California, recalling a hailstorm in 1997. “That has always stayed with me because it is one of the only times I’ve seen my father cry. For those of us that live very closely to the earth, we know that nothing is promised.”

Marti Menacho co-owns Olivas de Oro Olive Company in Paso Robles, California. Speaking about her olive grove, she notes, “This year, the trees are lighter. Last year, they could barely stand up; they had so many olives.” Her trees have fewer olives as a result of the natural forces of wind. “If it’s really dry and windy, the bloom blows off,” she explains. No bloom, no olives. No olives, no income.

“During the bloom season, we have to keep a lot of water on the trees so the flowers are more resilient and stay on,” says Menacho. The farm relies on water from a well, which requires the use of electricity, adding to a long list of production costs. Even if the blooms survive the spring, the fruit is susceptible to a particular kind of fly that destroys the olives. While a summer heatwave can kill off these flies, as has happened in recent years, hotter weather presents yet another set of challenges for farmers.

In California, high temperatures contribute to the extension of what is known as “fire season,” a period of time ranging from the start of summer to the end of fall when the state is most vulnerable to wildfires.

A few months into the pandemic, farmers in Northern California were faced with another round of heartbreaking losses as several hundred fires ignited across the state in a lightning storm in August, burning over three million of acres of land, including farmland, over the span of just a few weeks, and filling the air with smoke for hundreds of miles in every direction.

Darek Trowbridge of Old World Winery in the Russian River Valley of Northern California lost a vineyard to a fire in 2017. This year, heavy smoke lingering in the air forced him to harvest most of his grapes earlier than planned. Harvesting early means that Trowbridge will fortunately be able to produce wine this season, but he won’t be able to produce the wine he had originally envisioned or generate the revenue he had anticipated.

“Those of us who are awake to the growing climatic changes, we are seeing in our lifetimes unprecedented climatic event after unprecedented climatic event,” says Masumoto. “We just keep on setting records. The warmest winter on record. The longest drought on record.”

Add to that the August Complex, the largest fire in California state history (in terms of numbers of acreage burned), according to records kept since 1932 by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. This fire, along with five other fires that began during the 2020 fire season, are six of the state’s top twenty largest recorded fires.

Farmers are on the frontlines of the ongoing climate crisis, which began long before the pandemic and cannot be solved with a vaccine.

“I guess we’re sort of getting used to some large thing happening that we have to adapt to, rather than trying to fight it; but it’s been four years of hardship, and this was probably the biggest one so far,” says Trowbridge.

Small farms feel these challenges in a much more acute way than large agricultural enterprises, given the already painfully slim profit margins.

“When you go to a grocery store and you buy a carrot, typically for every dollar you spend, about a dime goes back to the farmer,” explains Wiig. “Ninety cents of that dollar ends up going to the grocery store, to the advertising, to the processing facilities, to the transportation, to the investors in those various businesses. Ten cents is not a lot to live on.”

This meager income generated by product sales is often stretched thin to endure the lengthy periods of production time that are fundamental in agriculture.

Peaches, olives, grapes, and most other fruit are grown from cuttings of mature plants that are grafted onto rootstock or planted in the ground, rather than from seeds. Once a new fruit tree or vine has been grafted or planted, farmers must wait years before they have fruit to harvest. For those following organic, biodynamic, and regenerative agricultural practices, the process can take even longer.

Although some trees can start to bear fruit after just a year or two, most trees—including apples, avocados and oranges—generally remain bare for at least three to five years. Even after a tree or vine begins producing, it may take as much as ten or twenty years for it to achieve maximum production. During these years, the plants require constant financial inputs such as labor, water, mulch, and machinery maintenance.

Inheriting mature plants that are already producing fruit, as was the case for Masumoto, Menacho and Trowbridge, does not necessarily make things easier or more financially secure.

However, earlier this year, time was on the side of some family farmers who found themselves uniquely positioned to confront abrupt market changes caused by the pandemic. While the industrial agricultural complex struggled to respond quickly to the crisis, small farmers were able to work with their small teams and local communities to create an opportunity in the midst of chaos.

Wiig believes the pandemic, and, in particular, early spring when food supply chain disruptions became visible in supermarkets, has motivated people to seek out ways of eliminating the extra links between themselves and the people who produce the food they eat.

“It was the golden era of CSAs,” says Wiig, referring to April of this year. “The silver lining of a tragic situation is that COVID brought a bigger spotlight for CSAs than anything has ever done.”

By now, the acronym (Community Supported Agriculture) has become ubiquitous, but relatively few have a firm grasp on just how important community supported agriculture is for farmers. While farmers markets and CSA programs both provide critical financial support for farmers, CSA programs offer the additional benefit of supplying farmers with upfront investments and a reliable source of income during growing periods when they don’t have any crops to sell, enabling them to pay their bills and workers.

As a direct result of the pandemic, numerous farms across the U.S. have begun offering CSA programs for the first time. Many of these programs take the form of a CSA box containing fresh produce, which is usually available for pick-up on the farm or at a specified location in a city center. Some farms, however, are also exploring models of community supported agriculture that provide consumers with the opportunity to actively interact with their food system and build closer relationships with local farmers.

Masumoto Family Farm has hosted its Adopt-a-Tree program for more than fifteen years. Through this program, participants can “adopt” a peach or nectarine tree on their farm and receive updates about the tree throughout the year, along with an invitation to harvest the tree in late summer.

The idea came from a desire to plant a particularly flavorful, but fragile peach. Rather than try to figure out how to ship the fruit to consumers, Masumoto and her family decided to answer another question: “What happens if we bring the eater to the farm?”

Over a decade after launching, the program consistently sells out of adoptable trees each year, often to repeat members. Seven years ago, the family also launched a Fruit Drive Thru program, enabling non-members of the Adopt-a-Tree program to visit the farm and pick up fresh fruit.

“Part of the power of developing direct channels of distribution with eaters is that we have so much more control over the process and the pricing,” Masumoto explains. “In the wholesale market we can grow the best peach we possibly can and we’re basically price-takers in the market—what’re they’re paying, that’s what we get.”

Olivas de Oro started their own adopt-a-tree program in 2007, and also has participants renewing their memberships each year. Members receive a photo of their adopted olive tree, along with information about it and a map indicating where to find it in the grove. They also have exclusive access to the company’s Olio Nuevo (olive oil fresh from the presses).

Members of the Adopt-a-Vine program at Old World Winery are similarly encouraged to visit their adopted plant. They also receive a bottle of their vine’s first vintage after adoption. But as Trowbridge sees it, the real value of the program for both the winery and the members is the perpetuation of their regenerative agricultural practices, which are key to Trowbridge’s land management approach as an organic and biodynamic farmer.

“The whole regenerative story is part of the narrative,” he says. “And that’s what people want to be a part of. They want to support that work, so they adopt the vine.”

In this way, CSA models can alleviate the strain on farmers resulting from limited financial resources and long-term time commitments, while also educating and engaging consumers.

“When we have a program like Adopt-a-Tree where we set the price directly, we have more power and we also have more clear avenues of communicating with eaters about what is happening on the farm. I think what happens with that is there is a shift in value because we’re opening a relationship that is beyond a single monetary transaction,” says Matsumoto.

Both Menacho and Trowbridge have seen members celebrate life’s most joyful events and commemorate its greatest losses in the company of their adopted trees and vines. By creating memories and forming personal bonds with these farms, members become invested—both financially and emotionally—in the wellbeing of the plants and people there, which means they may be more likely to help them weather future storms, no matter what form they take.

While transformation at the policy level to create a more just and sustainable food system will take time and collective effort, every individual has the power to enact positive change. The food supply chain disruptions of this year may be only a precursor to future crises if we all do not participate in and advocate for a new food system that supports farmers. And that means questioning where our food comes from during breakfast, lunch and dinner each day—a practice that has, fortunately, become more common recently.

Masumoto proposes “the hardest question to ask” in this moment: “What is our lifelong commitment to the type of food and the type of world we want to see, and how can we be seeding and nourishing that so this isn’t just a blip and these actually are lifelong changes?”

Right now, we are faced with so much uncertainty; but we can choose to make community-supported agriculture our constant and begin to answer that question in a way that acknowledges our responsibility to care for the people who feed us.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.