“Pa-ee! Pa-ee!”

I peer my head around the kitchen corner to see why my almost two-year-old is screaming for pie and—wait… we have pie? Standing on her tippy toes, in full toddler glory, she’s urging her fingers to grow toward her purple straw cup.

“Oh! Shabash! Pani,” I say, accentuating the last word, handing her the cup. “Water. Pani.”

She quenches her thirst in two swigs, eyes the bowl of fruit in my hand, then unceremoniously drops her cup onto the floor. “Nana!” she squeals, because everything is so dramatic at this age.

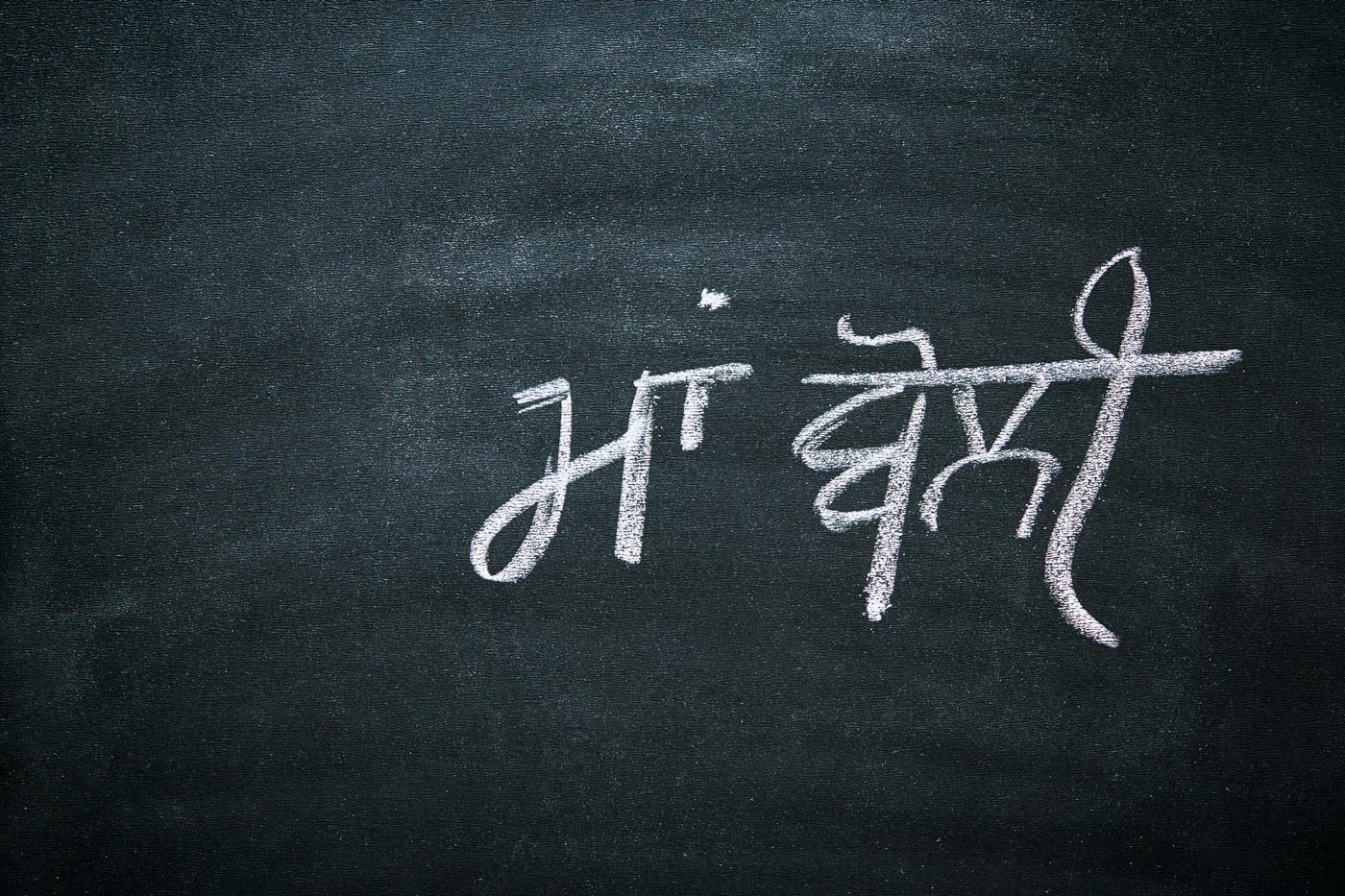

“Banana! Or kela. Kaaay-laaa,” I respond, overly stretching my mouth while she shoves two pieces of fruit into hers, murmuring something other than what I just said. Her older sister, close to six, has gotten a better grasp on comprehending Punjabi. My husband and I hope that one day, with enough repetition and exposure to my live-in mom, both kids will be able to understand and speak our native language.

Research has established the cognitive benefits of learning more than one form of speech, and according to studies, children who are exposed to two or more languages before the age of five are shown to have greater brain tissue density in areas related to language, memory and attention—even higher than adults who learn a second language. But it’s not easy raising bilingual kids, as any parent attempting the same feat can attest. Kids growing up in the U.S., Canada and other English-speaking countries are taught from nearly day one that “A is for apple,” and how Little Miss Muffet was spooked by an arachnid while eating her curds and whey. Nursery rhymes fill my ears daily—thanks, You Tube Kids—to the point where I’m humming, “I like to oot, oot, oot oopples and banoonoos” in the shower. I think I was cool once? I question while I rinse the shampoo away.

There is a valid reason children’s songs are centered around things we eat. Food is one of the earliest language touch points in a child’s life. From infancy, their little eyes watch their parents sip coffee, slurp cereal, and bite into sandwiches. Through watching, feeling and mimicking, kids get the hang of sticking morsels of nourishment into their own maws, masticating their food just like mama and dada. It is also through this same copy-cat behavior that children learn to speak. The word “language” originates from the Latin word lingua, meaning “tongue.” This small yet mighty muscle is central in both speaking and eating. The formation of sounds and words cannot be done without it, nor can the tasting and chewing of food. This natural pairing of food and language is apparent from childhood phonetics through our meal-obsessed adulthood.

Growing up, English was checked at the door in our home and the homes of my cousins. Sure, us first-generation Canadian kids would ramble on in English, throwing in some Punjabi words for added flavor and humor; but our immigrant Indian parents made it clear that with them—and folks within the same age bracket—our mother tongue was the only acceptable language for communication. Out of respect, if an aunty or uncle spoke in Punjabi, you responded in Punjabi.

Now that I’m older, I’m realizing my connection to my culture is deeply rooted not in Bollywood films, bhangra music, or bedazzled, technicolor fabrics—all of which are fabulous, by the way—but rather in this connection between Punjabi words and food. And I can give a lot of that initial credit to my maternal grandmother. My nani, who didn’t speak a word of English, was my pre-school caretaker and first food influencer, one who routinely shoved roti and masra di daal into my gob.

Corningware dishes, filled to the top with cholay, aloo gobi, kali daal, chawal, and accompanied with stacks of puri and roti, was the blissful norm of our childhood; and no matter our preference for English, we always called our culture’s food by its original name. Puri, not fried bread. Pindi, not okra. Matar paneer, not green peas and freshly made cheese. Most people can distinctly remember the tastes and smells of their youth, as well as the time periods and emotions linked with those eating experiences. For my brother and I, it was the eighties and Saturday mornings. The excitement of running into the haze creeping out of our tiny kitchen had a Pavlovian effect: Mom was making aloo prontay and today was now the best day ever. We’d watch as she piled coarsely mashed and seasoned potatoes into the middle of flattened atta, then folded the entire package up before rolling it square. We would fidget impatiently while the stuffed bread—oiled on both sides—sizzled on the tava, the smoke perfuming our clothes with Indian-ness. When she finally slid the first crispy pronta on to our plates, we’d quickly plop a few cubes of salted butter on top of the slightly charred surface, letting them melt on the way to the family room so we could watch Optimus Prime kick Megatron’s ass.

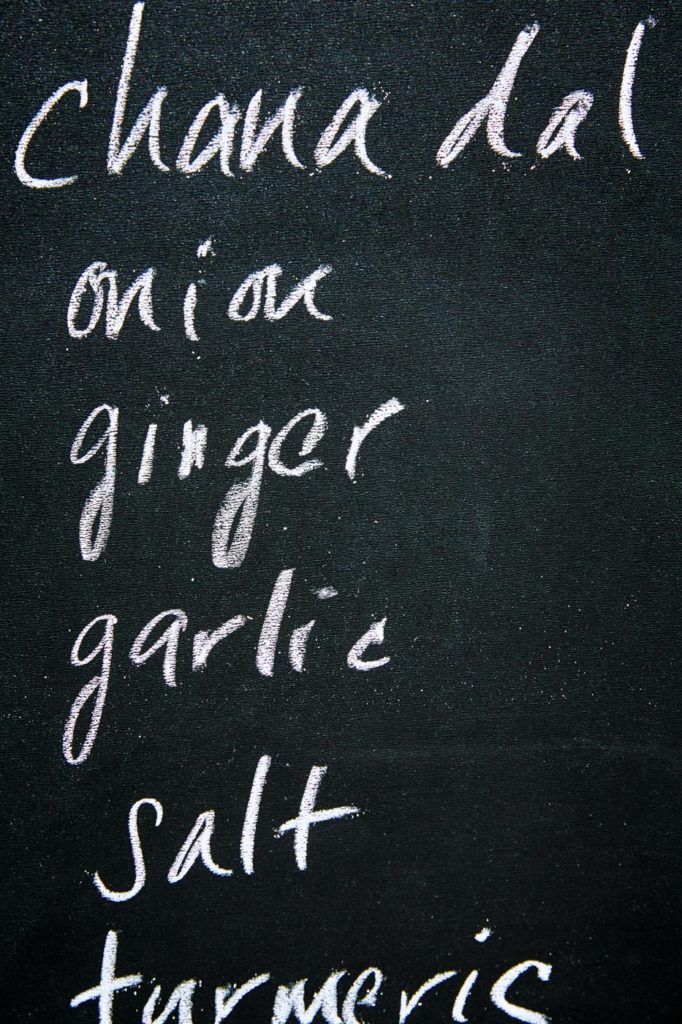

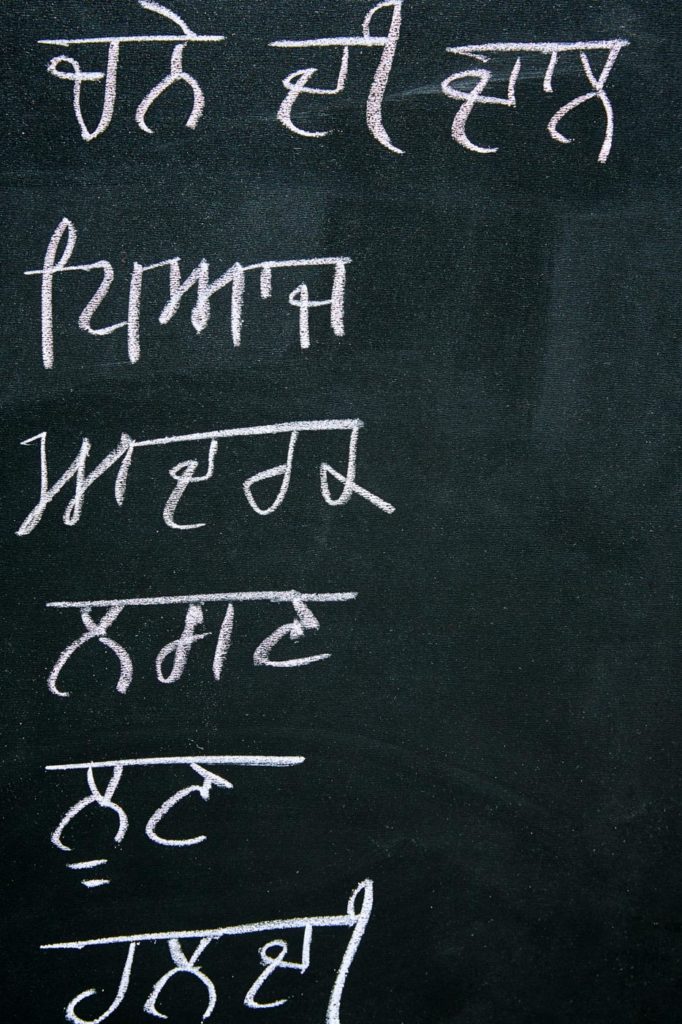

Hanging around the kitchen as a kid meant fetching things for my grandmother and mom: pyaaz (onion), lahsun (garlic), adrak (ginger), and tamatar (tomato) became routine requests since these ingredients form the base of many North Indian dishes. They used idioms to explain why I couldn’t stir the rice while it’s cooking or why we needed to heat haldi and spices in the frying pan before adding other ingredients. As I became more aware of other cuisines and recipes, I was acquainted with jargon like sauté, purée, flambé, none of which were ever used in our home. In ethnic cooking, terminology can sometimes refer to how ingredients are affected by water or heat, like the “reddening” of onions in hot oil—terms that don’t translate directly from Punjabi to English, but are somehow more comprehensible in their native form.

Although I feel a great sense of pride in my “diverse” background, growing up, I didn’t feel represented in popular culture (I’m looking at you BOP and Tiger Beat). So for many first-generation citizens, like me, and foreign-born Gen Xers and Baby Boomers, we found ways to “fit in” while looking outwardly different. From the shortening of one’s name form Jorge to Jo or Harminder to Harry, to altering one’s accent to become undetectable in order to avoid stereotypes. There was this notion that the more things we Anglicized about ourselves, the more we would become familiar—and less unsettling—to our white counterparts. That made going to the Indian Bazaar on Gerard Street—Toronto’s Little India—that much more special. It was an entire day spent mingling with people—from shopkeepers to fabric sellers and restaurant owners—without masquerading as a lesser version of who I truly was.

Immigrant-owned restaurants in the seventies and eighties were also feeling the pressure to assimilate. To bring in a wider demographic, some mom-and-pop joints used English descriptors instead of the actual names of dishes. “Curry” became synonymous with any saucy Indian dish. Brothy ramen and udon bowls were reduced to “noodle soup.” Khao Man Gai and arroz con pollo were simply referred to as “chicken and rice.” Sure, this made things easier for the masses. But were we intentionally stripping our culture away from the very things that made up our culture? When the explanation becomes the dish, do we lose a part of that culinary heritage?

All recipes come from somewhere, and with ethnic foods, that usually includes a long history of overlapping civilizations over periods of time. Cuisines vary from region to region within the same country. Take strand pasta—most commonly known as spaghetti—for example. In Italy, from boot to heel, it varies from vermicelli, capellini, strangozzi or fedelini depending on the vernacular of the city. There’s also an emotional connection to food, one cemented by stories of hardship or prosperity shared through meals prepared by grandmothers, aunts, mothers and mother-in-laws.

I don’t want my daughters to hide who they are, but instead wear their identity like a shield of armor. Nor do I want them to feel the need to make things easier for other people—neither my generation or that of my parents were granted this courtesy. And by continuing this pattern of oversimplification, we are doing a disservice to both parties. The intertwined relationship between culture and food is nothing new; trying different cuisines is an opportunity to learn, especially in a place like the U.S. where assimilation feels almost forced at times.

Thankfully, there has been a growing shift back to the indigenous names of dishes, especially in the recent wave of second-generation restaurants and cookbooks covering a myriad of international cuisines. Teaching my eldest daughter how to roll her r while saying sofrito then switching to a guttural r for crème brûlée is actually quite enjoyable. Perhaps it’ll spark the desire to learn Spanish or French.

Roughly two-thirds of the world’s population can speak two or more languages; in the U.S., that number is much lower (approximately twenty-five percent of U.S. children hear another language at home). That estimate is expected to rise thanks to immigration and to parents who are instilling their culture into the home. Being different is hard, no question, and even more distressing to kids whose skin hasn’t toughened with age and experience. But if we are to teach this young generation to respect other cultures, it is equally important to teach them to respect their own.

——

Bone Deep is an ongoing column in which contributor Deepi Ahluwalia digs into her curiosities about food, exploring its historical and global significance.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.