Editor's Note

In her new column, contributor Deepi Ahluwalia digs into her curiosities about food, exploring its historical and global significance.

I geek out over food.

I want to know where it comes from, who made it, and the history behind it. I love learning about different ingredients, their significance, and how cultures utilize them. In culinary school, I started reading On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen by Harold McGee just for fun. For me, getting to know the why behind food leads me to understand the taste of food.

So naturally, when I first heard of terroir, it intrigued me. It was a common enough term in the wine industry, but was that the extent of it? Did terroir affect other products? If so, how? I knew if I wanted those answers I’d have to do some digging. The nerd in me loved that.

Derived from the French word terre, meaning “earth,” terroir refers to the environmental factors that affect crops in specific regions. Most often used when describing the subtleties of different wines, terroir is responsible for the unique characteristics found in certain foods—it’s what gives some coffee brightness and some chocolate floral notes. To simplify things further, terroir implies that it’s impossible to exactly reproduce certain products outside their place of origin—even when following precise traditions and methods—because the conditions and characteristics of that land are unique. There’s an actual term for this: site specificity.

The French are pretty passionate about terroir. So much so that they have an entire system based on it. The appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC)—which translates to “controlled name of origin”—is a designation of process and provenance. The AOC ensures the identity of specific products with a strong sense of terroir are protected in the marketplace. It’s because of the AOC that Comté cheese can only be made in the Franche-Comté region of eastern France (to very specific standards), and why champagne can only be made in the Champagne region of France (all other bubbly is considered “sparkling wine”). Other countries also have AOC-equivalent programs—Italy has the DOC (Denominazione d’Origine Controllata) and DOP (Denominazione di Origine Protetta) and Spain has DO (Denominacion de Origen). Terroir also affects the price of these agricultural commodities, as well as the products made from them. Associating an item to a particular region or farmer speaks to its quality and authenticity.

But what exactly determines a region’s terroir? Well, there are many factors. Soil type, elevation, rainfall, sunlight, temperature, geomorphology and neighboring plants all contribute to the characteristics of that land. All of these criteria influence how the end product will ultimately taste.

Wine

I’ll be the first to admit wine intimidates me. It’s one of the few things in the culinary world that makes me question my intelligence. I often read descriptors like “crisp, sweet rieslings” or “spicy syrahs with strong pepper tones” or “a pinot noir with concentrated notes of chocolate and black cherry,” all of which I can relate to. But wine labels aren’t as conversational. The varietal of grape in California and other New World wines—produced in the U.S., Australia, Argentina, Chile, New Zealand and South Africa—is clearly displayed on their respective bottles. If you know the attributes of the grape, you can make an educated guess on how a wine will taste. But the French believe the appellation—the terroir—is the dominant influence in a wine. Old World wines—made in France, Italy, Germany, Spain and Portugal—prominently tout the region or vineyard on their labels versus the varietal of grape, assuming you should already know the type of grape grown in the region. Thankfully, the popularity of California-style labeling has convinced some European winemakers to adopt more user-friendly labelling.

Even though a varietal can be found outside its place of origin, the taste of the wine it produces will vary because of where it’s grown. Let’s take chardonnay as an example. It is one of the most widely planted white wine grapes—both in the Old World and the New World—with a range of flavor profiles. Even within Burgundy—where it is the signature white grape—it offers the rich and creamy wines of Pouilly-Fuissé to the minerality of chablis. In California, chardonnays present citrus notes with hints of melon. The fermenting of these wines in oak barrels also adds toasty and buttery tones, such as vanilla and toffee.

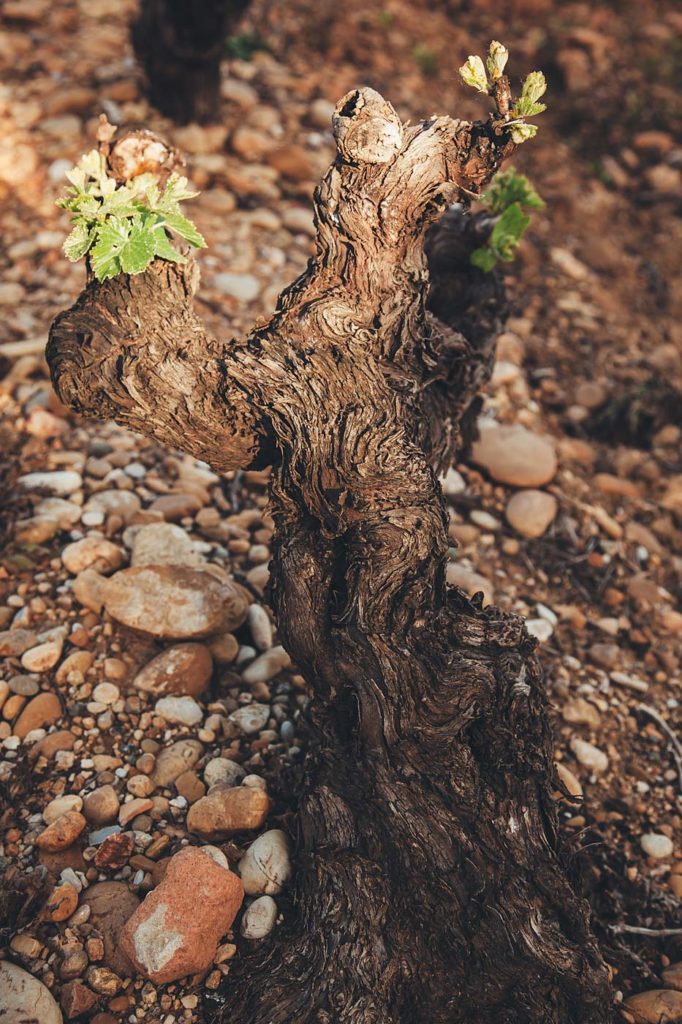

A wine’s complexity begins with its grapes and the vineyards in which they grow. It is the job of the vigneron (“wine-grower”) to bring out the expression of a wine’s terroir.

Coffee

When I’m ordering an espresso or macchiato, I’m usually not thinking about terroir. Nor does it cross my mind when I’m sipping a latte with my after-dinner dessert. I just know it tastes delicious, and that I usually want a second cup.

To understand the world of coffee—and why certain brews taste better with certain foods—you have to again understand terroir. This too can change year to year. If there is an abnormally dry or wet growing season, it can impact how that particular coffee will mature, impacting the taste of brews made from that year.

Acidity and sweetness can vary depending on elevation. Beans from Latin America—grown throughout the jungles of Central and South America, as well as Colombia, the Republic of Panama, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Mexico and the Caribbean islands—are grown at high altitudes in volcanic soil, giving them brightness and sweetness with a light body and high acidity. These coffees make for great morning cups of joe. Africa—the birthplace of coffee, specifically Ethiopia—produces coffee with great depth, much like wine. Typically, the ancient-growing regions of Africa and the Middle East—such as Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Côte d’Ivoire and Yemen—are grouped together because of the similarities in their coffees. With medium acidity, these coffees have notes of berries and spices, with strong chocolate undertones in regions where there is cacao production. Southeast Asia and some Pacific islands—specifically Indonesia, Sumatra, Papua New Guinea and Java—produce coffee which tends to be very strong (and slightly bitter) with smooth flavors, lower acidity and earthy tones. These coffees pair nicely with a nibble of chocolate or a full-on dessert course.

Tea

I love tea. It is my hot beverage of choice and how I start my day each morning. I love the complexity of tea; it’s sophisticated yet strong, graceful yet assertive. Qualities I like to think I possess (insert wink emoji).

The attributes of tea are directly linked to terroir. With tea, it’s all about the leaves. Tea bushes that grow in sunnier areas tend to be stronger—and potentially more bitter—as these leaves grow more quickly, allowing little time for flavor to mature. Higher elevation teas—which are shrouded in mist and are in cooler climates—have a slower growth rate which concentrates flavor.

An abundance of rainfall and well-draining soils are also favorable conditions found in mountainous regions. The concentrated teas produced in these areas is one reason why high altitude teas are so distinctive. Nilgiri tea—also known as Blue Mountain tea—is grown in Southern India in the Western Ghats mountains. In late-January, a light frost appears on the tea bushes. These damaged leaves are quickly harvested and processed, resulting in a tea that is dark and intensely aromatic with distinct muscatel notes. The Wuyi Mountains of northern Fujian, China is home to “rock teas” or “cliff teas,” such as Da Hong Pao. Grown high atop limestone peaks, these tea bushes are heavily shaded by clouds and mist, only getting a few hours of sunlight each day. The thin, rocky soil gives these teas a unique minerality with notes of honey, cinnamon and fruit.

Chocolate

Steve Jobs once said, “You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future.” I truly believe that if it wasn’t for chocolate, I probably wouldn’t be working as a food photographer and writer. I found the process of creating chocolate—from bean to bar—so intriguing that it ultimately fueled my decision to study pastry arts, thus opening the doors to the food world.

The connection between terroir and a chocolate bar may not be obvious, but keep in mind, chocolate gets it start from the beans of the cacao fruit. Grown in the tropical belt—20 degrees north and south of the equator—these beans can vary in flavor despite the limited area they grow in. Madagascar beans are characteristically fruity—with notes of plums, berries, citrus and raisins—whereas Ecuadorian beans lean toward more earthy, nutty, floral and woody tones.

Single-origin chocolates give us the best indication of a region’s terroir, taking us to the soil, air, aromas and flavors of the land. Côte d’Ivoire—the world’s largest supplier of bulk chocolate—produces a bold and non-complex chocolate that offers little acidity and bitterness, with underlying flavors of tobacco and leather. Hawaii—America’s only cacao industry and home to some of the most expensive cocoa beans due to limited planting—offers chocolate that has bright, tropical, nutty and berry-like tones; whereas in the Dominican Republic, chocolate displays notes of cinnamon, cloves and tropical red fruits. Northern Peru, considered to be one of the original sources of cacao, produces chocolate with unique aromas of green grass, flowers and damp earth, akin to the vegetative scents found in the woods.

Cheese

One of my favorite food memories of France—amongst all the delicious meals eaten between Provence and Paris—is my daily snack of a crunchy, chewy baguette and a wedge of stinky cheese.

When the term terroir is applied to artisanal cheese, it includes not only aspects of the land but also the animal—usually cow, sheep or goat—and naturally occurring molds. A wide variety of factors contribute to the end product: the geography of the land, bacteria in the area, the grass eaten by the animal during a particular season, milking schedules, aging process, to name a few.

Farmstead cheese is traditionally made with milk from the producer’s own herds. In mass production, however, milks from different dairies are often mixed and adjusted to meet stringent criteria, including protein and fat content. These producers are after consistency—they want one batch of cheese to taste just like the next batch, and like the one produced three months down the road. On the flip side, artisan cheesemakers celebrate nuances in flavor and color, as these characteristics set their cheeses apart from the rest of the pack.

Roquefort—one of the oldest types of cheese dating back to Roman times—was the first cheese to receive legal protection against imitation—the first appellation d’origine contrôlée for food—in 1925. The combination of its tangy flavor, legal protection, and the quintessential taste of the natural Combalou caves of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon that roquefort cheese offers is rare, though parmigiano-reggiano follows closely in its footsteps. The importance of terroir in parmigiano-reggiano is directly linked to its locality: the water the cows drink, the food they eat, the milk used to make the cheese and the air surrounding the cheese as it ages—all are specific to the provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Bologna (west of the Reno) and Mantua (south of the Po). Nothing that contributes to the cheese comes from outside this region, and that defines the salty, crystalline cheese that has fostered so many imitators.

The Importance of Terroir

We can learn many things about food if we pay attention to where it comes from. Terroir lets us experience the history and traditions of a place through our palate. It makes us aware of the effects of climate and how certain regions have—and are—adapting year after year. It allows us to reconnect with the land, forcing us to slow down and pay attention. And the best part, terroir takes our senses on a tour of far-off lands, a trip that we can take anytime, anywhere.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.